Abdar Rahman Koya

Abdar Rahman Koya

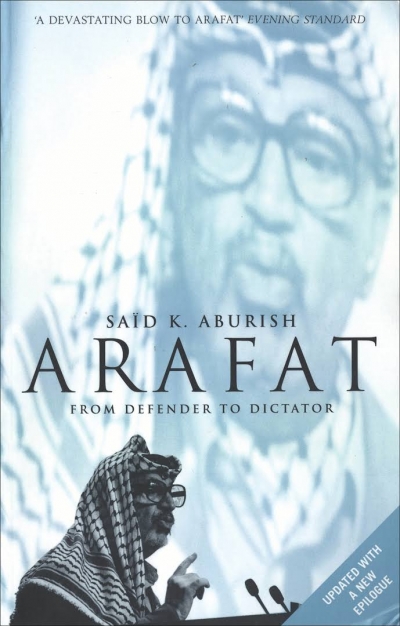

Arafat: From Defender to Dictator by Said K. Aburish. Pub: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, London, UK, 1999. Pp: 360. Pbk: £7.99

Celebrity biographies have become a major part of the western publishing industry. Many of these biographies are of contemporary political leaders, whose names are familiar to readers from the news, and virtually all are written within a political framework that suits the west’s political agenda. Recently, Muslim politicians and leaders have attracted biographical attention: king Hussain of Jordan, Saddam Hussein, Imam Khomeini and others, whose profiles in the west (as hero or villain) have been very different, but all of whom have had a market. One such man is Yasser Arafat, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), who has the rare distinction of having been both villain and hero in turn.

Said Aburish’s Arafat: From Defender to Dictator is just one of a number of books reflecting fresh western interest in the man who was condemned as a terrorist for years, until being re-discovered as a ‘man of peace’ after auctioning off the Palestinian cause at Oslo in 1993. Aburish, a Christian who lives in the west and holds an American passport, considers himself well-equipped to write about Arafat. Being an Arab, Aburish hopes to debunk some of the myths which, he says, invariably rise to the surface whenever an "outsider" writes about Arabs. In his introduction, Aburish attributes such myths to a "cultural divide which foreign writers cannot bridge and a lack of understanding of today’s Middle East and its politics."

Aburish, however, fails dismally to lived up to his promise of providing a more sympathetic analysis, instead falling into racist characterisationshimself. His use of derogatory expressions normally found in western works, such as "wily Arab tribal chief," which he uses to describe Arafat’s leadership, makes it difficult for readers to be convinced of his objectivity. Elsewhere, Aburish laments that the "legendary Arab lack of organisation" was evident among the Palestinian groups opposing the zionist occupation. Yet the book itself consistently balances its condemnation of Arafat with flattering comments, as if to demonstrate the author’s ‘non-biased’ view.

Aburish, himself from Jerusalem, also carefully casts aside the Islamic dimension in the Palestinian conflict. His use of jargon such as "Islamic fundamentalists" only reinforces the reader’s suspicion that he had his own agenda when he set out to write about Arafat. Again, his use of the term "folk mentality" in describing Arab Islamic leaders reflects a contempt for them that appears to have clouded his judgement.

The book gives more space than one would expect to Arafat’s early life and personality, which, Aburish says, has often been confused by Arafat’s own contradictory claims. The book gives readers some interesting anecdotes from Arafat’s early life that were previously unknown. According to Aburish, Arafat comes from an elite Palestinian background and his family has grown ever richer. He was not interested in studies, and barely managed to complete a civil engineering degree; in his youth he ran a gang of "neighbourhood children" who employed bully tactics; he had a difficult relationship with his father, whose funeral he did not attend and whose grave he never visited. Arafat was also close to Hajj Amin al-Husseini, the revered mufti of Palestine, in the 1940s.

Being a Christian, it is not surprising that Aburish often refers to Arafat’s Egyptian origin when he wants to emphasise that Arafat is ill-qualified to represent the ‘Palestinian cause’. The author’s failure is his refusal to recognise that the Palestinian question is not a purely Palestinian cause, but an Islamic one, because of the special reverence Muslims have for al-Aqsa mosque. It was for this reason that the late Imam Khomeini (a non-Arab) laid such great emphasis on the Palestinian cause that he declared the last Friday of Ramadan to be Yaum Al-Quds — Jerusalem Day.

Many times in the book, Aburish tends to get too personal in his condemnation of Arafat’s character. For example, he even asks why the young Arafat once applied for admission to the University of Texas, despite his "anti-Americanism". He then takes yet another swipe at Arabs in general: "It was no different from the anti-Americanism of most Arabs, which has always fallen short of boycotting the USA or taking concrete action against it," he writes.

This book, however, has its own achievement: turning the popular western perception of Yasser Arafat upside-down — from a heroic freedom-fighter who has kept the hopes of millions of displaced Palestinians alive to a narrow-minded operator, out of touch with reality, whose personal ambitions have led to a rule based on cronyism in which the people around him are rewarded with jobs and money despite their incompetence.

But for Muslims the author’s own solution is laughable. Aburish himself is not a great fan of the Oslo ‘peace accord’ and has often spoken out against wasting one’s time at the negotiating table. A contradiction, however, lays bare his own agenda for Palestine. At one point he berates Israel as bereft of generosity towards the Palestinians and any attachment to peace, saying that the Oslo agreements were vehicles for Israel to further its expansionist policies. Then, almost immediately after that, he offers his own solution: replace Arafat with a "triumvirate of Heidar Abdel Shafi, Faisal Husseini and Hanan Ashrawi," a group he believes is capable of "negotiating a better deal" with Israel.

Aburish also exposes the shaky foundations of Arafat’s leadership, and shows that the PLO has never been a revolutionary movement. The PLO was even reluctant to support the intifada which erupted in 1987, although it later claimed to have launched and led it. At the time, Aburish says, "it was Arafat who... manifested the most reluctance to provide the rebellion with support because he feared the effects of another failure on his already reduced position."

Aburish reveals that since 1963, when Arafat first established contact with the CIA in Beirut, the PLO has been involved in secret talks with the US, effectively a betrayal of its people. Readers, however, do not need people like Aburish to tell us the obvious fact that Arafat has created one of the ugliest expressions of absolute dictatorship even by Middle Eastern standards.

Throughout the book, perhaps unconsciously, Aburish has given so much attention to explaining Arafat’s personality that, in the end, what one gets is not an understanding of how Arafat’s early life shaped his future activities, but how the author himself thinks the Palestinian conflict should be perceived. The reader’s suspicion about the author’s hidden agenda is confirmed when Aburish heaps praise on George Habbash, the Palestinian Christian activist, while condemning Muslim groups as suffering from "folk mentality" (whatever that means).

Ultimately, this is a book about Aburish’s perspective of the Palestinian conflict more than about Arafat himself. And frankly, Aburish’s perspective is as irrelevant today as Arafat is.