Umar Shahid

Umar ShahidWhile the rise of Russia is seen as a good sign to contain America’s belligerence, on the flip side, Moscow is courting the Serbs in Bosnia threatening the Muslim majority country in the Balkans.

In 2010, Crescent International’s short field research in Bosnia pointed out that “rational policies formulated on universal Islamic ideals can neutralize the leverage of imperialist powers by making Croats, Serbs, and Bosnians partners. The Bosnian Muslims cannot duplicate the experience of Iran, Turkey, or Lebanon; they must take account of the very different environment in which they operate. This, however, does not mean that the Bosniaks must surrender to hegemonic imperialist powers or compromise their fundamental rights.”

Not unexpectedly, no authentic indigenous Bosnian socio-political force or program has emerged in Bosnia since 2010. Today, all politicized forces in Bosnia function within NATO’s political and security parameters established at the end of the genocidal war waged against the Bosnian Muslims in 1992–1995. It appears that due to the rise of Russian global influence this might soon change, but it is not good news for Muslims in Bosnia.

Results of the October 2016 parliamentary elections in Bosnia show that the divide between Catholics, Muslims, and Orthodox Christians of Bosnia is the hallmark of Bosnia’s political scene. Analyzing results of the recent elections in detail would not serve any useful purpose at this stage. Instead, this article will focus on the geopolitical shift that will most probably occur in the Balkans in the near future due to the rise of Russia’s global influence.

Reporting on the election results, the US-financed Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty (RFERL) highlighted how just before the announcement of the preliminary election results on October 3, the leader of Bosnian Orthodox Christians, Milorad Dodik, pointed out to a local journalist that he was just speaking to Moscow on the phone, signaling his connections to Russia. RFERL’s focus on this point was a hint that the US is watching Russia in the Balkans very closely.

Dodik who is known for his provocative Serbian nationalist political gestures, visited Moscow on September 22 where he was greeted almost like the head of state by Russian President Vladimir Putin. This took place just three days before the banned “referendum” in the Orthodox Christian part of Bosnia. While the referendum was about a simple religious holiday, most Bosnian citizens saw it as a rehearsal for separating from Bosnia as it was banned by Bosnia’s Constitutional Court on September 17.

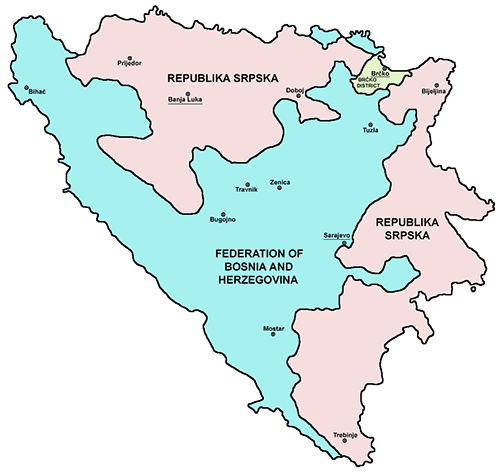

Dodik’s visit to Moscow of course alerted the US and its Western allies who brought Bosnia under NATO influence after the end of the war in 1995. Thereafter, there was a de facto partition of Bosnia by Washington and its European allies into three sectors making sure that Muslims would never exercise real sovereignty over a proper state within Europe.

Dodik’s visit to Moscow and his frequent pro-Russian overtures probably raise red flags among Bosnian Muslims, as Moscow sees weakened Serbian nationalism in the Balkans as a historical injustice and Russia’s own weakness. One should not forget that Russia entered the First World War once Western powers began mobilizing against Serbia. Russia has always viewed Serbian dominance over the Balkan region as a pillar of its security and a key leverage against Western powers.

In the 1990s, Russia lost Serbia as leverage and today the Russian press is full of regrets over Boris Yeltsin’s weak politics that failed to protect Serbia from NATO aggression. Moscow played on similar nostalgic feelings when it invaded Ukraine and brought Crimea under Russian control.

While the Western press still debates what Moscow’s key policy objectives are in its current revived form, in this magazine we have been arguing since 2013 that Russia’s aim is to gain strategic leverage over Western powers in order to use it as a negotiating tool to secure Western non-involvement in the territories of the former Soviet Union.

Moscow’s actions in Ukraine and Syria clearly reflect this goal. Nevertheless, it appears that Moscow might be upping the benchmark, as it rightly sees the US as an empire in decline. This does not mean that Russia will seek global dominance, at least not yet. The Russian political elite knows well that Moscow does not have the required stamina to be a global hegemon, but it will definitely seek greater concessions from the empire in decline. It is also important not to confuse Moscow’s rivalry with the West as ideologically driven. Contemporary Russia is not the Soviet Union and most members within the current ruling Russian elite view the West as a civilizational reference point and do not seek to create their own paradigm.

Nevertheless, Moscow sees it as necessary to create as many leverage points as possible against NATO regimes and prepare them to be activated at the opportune moment. It would, therefore, be naive to assume that Moscow is going to ignore the Balkan region where it has historical, cultural, and according to the Russian Orthodox Church, existential interests and bonds with the Serbian nation.

The reality is that most Serbs see NATO as the prime culprit in destroying the aggressive Serbian nationalist myth by facilitating the independence of Kosovo and Montenegro. Muslim Bosnians on the other hand, view NATO as the lesser evil that helped to preserve Bosnian statehood. The historical reality of the region is such that if Moscow decides to activate the Serbian nationalist card in order to destabilize Europe and pressure Washington into respecting Moscow’s redlines, Bosnians will have no other choice but to turn to NATO for protection.

It is almost a political axiom to foresee Bosnian Muslims in the NATO camp during the next Balkan standoff and authentic Islamic movements elsewhere have to accept this fact in a pragmatic manner. Failure to do so will further strengthen sectarianism and allow the Saudi regime to use its surrogate status with the US to position itself as the savior of Bosnian Muslims and thus prolong its soon to expire shelf-life. Islamic organizations in Bosnia did not manage to formulate an alternative paradigm to the NATO-instituted order in Bosnia and Muslims elsewhere were too busy with solving their own strategic dilemmas to be of any help to the Bosnian Muslims. Thanks to NATO imperialism, Muslims were kept busy in their own local problems.

At present it is not completely clear how exactly the next upcoming Balkan tension will play out but the rise of Russia is certainly not good news for Muslims in Bosnia since Moscow sees Serbian nationalism as its strategic leverage. The only Islamic force that could influence Moscow to readjust its mindset on the issue is Islamic Iran. Moscow has gotten itself too deeply involved in Syria where it cannot do without Tehran’s help. Iran’s quid pro quo with Russia could be Bosnia’s policy option. What can Bosnia offer Iran? Its progressive Sunni Islamic establishment which must not be connected to Western presence in Bosnia can play a very constructive role in reducing sectarian tensions in the Muslim world.