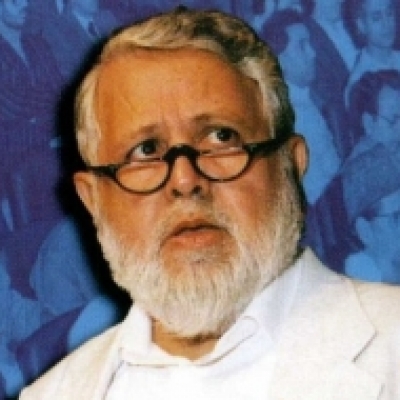

Kalim Siddiqui

Kalim SiddiquiOn April 23, Crescent International and the Institute of Contemporary Islamic Thought (ICIT) will hold a Kalim Siddiqui Memorial Conference in London to mark the tenth anniversary of the death of one of the Islamic movement’s modern giants. The theme of the conference will be The Islamic movement: between extremism and moderation. As another part of our commemoration of Dr Kalim’s work,Crescent International is reprinting some of his major works, beginning with the introduction he wrote for a book that was never published. This paper outlines his understanding of the Islamic movement and the challenges that it faces.

This book, or one very like it, would be published about now even if there had been no Islamic Revolution. I set out to develop these ideas a long time before the Islamic Revolution burst upon the stage of history. Without the Islamic Revolution and Imam Khomeini this book might have been more tentative. The Islamic Revolution has created in Iran a much-needed living laboratory for the testing of these ideas. The central theme that runs through this book is that of the “global Islamic movement”, of the world of Islam without national frontiers pursuing the political goal of Islam in all parts of the world.

The global Islamic movement is the central overarching framework that encompasses the Islamic Revolution and its ‘big bang' effect on the Ummah, calls for new Islamic Revolutions in all Muslim areas of the world, brings about a convergence of Muslim political thought, purifies Muslim thought from the infiltration of western political ideas, defines the political methodology of Islam, and sets the agenda for a generation or more of Islamic activism. From personal experience and active involvement in the underlying current of Muslim political thought from an early age, I know that a large body of Muslim opinion was beginning to look for alternative solutions to the political ills of the Ummah long before the Islamic Revolution. For the perceptive observer the evidence of this strong undercurrent of dissent was everywhere, but its expression was suppressed. The best-known expressions of these ideas are to be found in the writings of Sayyid Qutb. He invented the term ‘American Islam' and paid dearly for it. He was executed in 1966, accused of sedition by Gamal Abd al-Nasser. Qutb's short book, Milestones, is certainly a turning point in Muslim political thought. The failure of Qutb's book to turn the course of history, or even to prise open the grip that ‘American Islam' had acquired over modern Muslim political thought, can only be explained in terms of the skilful use of Islam made by the Saudi regime and bankrolled by petrodollars. To be fair to Qutb and his book, books in themselves do not bring about revolutions, at least not soon. Milestones was translated into many languages, including Persian, and was widely published and read. It is still one of the most influential books of its kind in the world of Islam. It is difficult to measure Qutb's direct influence on the Islamic Revolution, but the Islamic government in Iran has acknowledged its debt to him by issuing commemorative stamps. It can be argued that Milestones alone created more political consciousness among Muslims everywhere than all the works of such men asAbul Ala Maudoodi and other writers of this period put together. In effect, Qutb created the intellectual climate that was to prove so receptive to the ‘big bang' effect of the Islamic Revolution.

I first became conscious of belonging to a great tradition of Muslim political activism when only a schoolboy in northern India. Already Muhammad Ali Jinnah's bandwagon was rolling inexorably towards Pakistan. I joined gangs of Muslim boys who beat up Hindu boys and threw stones at trains carrying British troops. India was partitioned on August 14, 1947, and I arrived in Karachi on July 1, 1948, on board a refugee-ship from Bombay. Two months later I was among the weeping throngs at Jinnah's funeral. The Islamic content of the Pakistanmovement was marginal and cosmetic for the leadership, but real in the new-found political consciousness of the Muslim masses of British India. For the Muslims of the subcontinent, the creation of Pakistan had been an ‘Islamic Revolution', except that it had not led to the setting up of an Islamic State. Its only outcome was the setting up of a secular Muslim nation-State whose leadership was largely corrupt, politically subservient to the west, and incompetent to boot. Pakistani rulers of this early period, like their counterparts elsewhere, quickly learned to use ‘American Islam' to disguise their own alienation. The other role of ‘American Islam' has been to keep the world of Islam divided into nation-States. I return to this theme again and again.

Student politics in Pakistan, especially in Karachi, grew both volatile and violent in the early 1950s. The Muslim League's role as the ‘party of solidarity' broke down as its feudal wing and the inherited colonial bureaucracy took control of the infant State. A broad Islamic movement representing the raw emotions of the Muslim masses, stirred by the bloodletting of partition, began to clamour for an Islamic State. The best-organised of these Islamic groups was Maulana Maudoodi's Jama‘at-e Islami. I sensed then that the Jama‘at was trying to be little more than an Islamic version of Mr. Jinnah's Muslim League. I joined a smaller student group that called for a return to the classical khilafah. I started and edited the group's twice-monthly paper, Leader, from 1952 to 1954. During this period I read virtually everything that was available in English and Urdu on issues of State and politics in Islam. This literature fell into two broad categories. On the one hand there were the theological writings that extolled the pristine purity of Islam and the glory of the early khulafa al-rashidoon, and on the other there were the confused outpourings of the colonial period. All very depressing. The events that stirred us in those days were the Musaddeq era in Iran and the July 1952 ‘revolution' in Egypt. I recall writing stirring editorials denouncing American and British intervention in Iran and Palestine. I also denounced the Middle East Defence Organisation (MEDO) that was proposed by John Foster Dulles, US Secretary of State in the first Eisenhower administration. MEDO subsequently became the Baghdad Pact. After 1952 many members of al-Ikhwan al-Muslimoon came toKarachi believing that the soil there was more fertile for Islam than in Egypt under Nasser. Among them was Said Ramadan, the son-in-law of the assassinated founder of the Ikhwan,Hasan al-Banna. The curious thing was that the Ikhwan elite came to Pakistan looking for inspiration from us, while we in Pakistan hung on to every word they spoke, trying to learn from these Arab ‘revolutionaries'. The sad fact was that it was a case of the blind leading the blind. We were all in a swamp-like wilderness created by the excessive rhetoric of secular, nationalist, feudal and corrupt leaders and rulers who were imposed on us by the colonial powers in the name of independence. It has to be said that the Islamic movement at this time consisted largely of dreamers, and a large number of confused intellectuals and wayward students. No one, not even Maulana Maudoodi, had grasped the post-colonial historical situation as it really was.

The FLN's armed struggle in Algeria was launched in November 1954. By then a few of us from the student group of Karachi had arrived in London. Here we organised weekend discussion groups and formed Britain's first students' Islamic society at the University of London. But soon it became clear that most of us were little better than the ‘careerists' and ‘self-seekers' of other ‘Islamic' groups in Pakistan. We met Ikhwan leaders living in exile in Europe. Their lifestyles and preferences for official patronage from Saudi Arabia exposed their hollow revolutionary credentials. The joint British, French and Israeli invasion of Egypt in 1956, over the nationalisation of the Suez Canal, had strengthened the demagogic role of Nasser. TheFLN's victory in 1962 and the French ‘withdrawal' from Algeria (‘great' powers are never defeated, they only withdraw) gave a temporary uplift to our sagging morale. This was soon turned into another nightmare when Ben Bella and the FLN's francophile leaders dropped the victory of Islam as their platform and settled instead for the ideas of Franz Fanon, Che Guevara and Mao Tse Tung. We had once again plunged into total darkness, to be made worse by Sayyid Qutb's execution in 1966 and the Israeli occupation of al-Quds, the West Bank, Ghazzah, and the Sinai in l967. Two years later the zionists tried to burn down al-Aqsa in Jerusalem. This led to the first ‘Islamic summit' in Rabat, which, despite its pomp and splendour, was a living demonstration of the impotence of the post-colonial nation-States to act together or effectively in defence of Islam. The break-up of Pakistan in 1971 was openly welcomed, applauded and even celebrated throughout the world. Clearly, for the enemies of Islam, domestic and foreign, the world of Islam still consisted of areas of potential threat to their global interests in the future. Wherever possible, these were to be broken up into smaller, weaker and more subservient client States.

During the sixties I ploughed through libraries in and around the University of London, taking a doctorate in political science in the process. Relief subbing at the Guardian, then in GraysInn Road, two nights a week and in summer months, paid my bills. In 1969 and 1970 I visited Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, India and what was then East Pakistan. Turning 40 after 10 years inBloomsbury's wilderness I had reached a number of conclusions on all major issues facing the world of Islam and Muslims at this time. But first came my book on Pakistan. The central ideas developed during these years formed the basis of the Draft Prospectus of the Muslim Institute, published in 1974. Two papers, written during 1976 and 1977, are also important. These are The Islamic Movement: A Systems Approach and Beyond the Muslim Nation-States. The latter spells out our basic position: that it is not possible to establish Islamic States, or to develop an Islamic civilisation, on the basis of the nation-States created from the infected bowels of colonialism. The nation-States would have to be dismantled and the political map of theUmmah redrawn. In the earlier article I argued that there existed an underlying unity of the Islamic movement worldwide. It is couched in the jargon of systems analysis, but the message is clear. This is the other central plank of the political thought developed at the Muslim Institute: that Islam is a global movement and its first duty is to establish Islamic States. This idea was expressed in the Draft Prospectus thus:

It may well be that a model society will have to be created in one geographical area before the pace of change can be accelerated in other areas.

The tone of the Draft Prospectus was cautious because we felt that no change for the better was imminent. In Towards a New Destiny (1973) I wrote:

It is obvious that political, economic, social, cultural and intellectual decline has continued in most Muslim countries in the years since independence. It may well be that this is likely to continue for perhaps another generation or more. It may even come to pass that many of the Muslim countries of the Middle East will have to endure another period of colonial rule underzionism, supported by both the United States of America and the Soviet Union. If this happens in the Middle East, with Iran under the shah, Pakistan under the virtual hegemony of India, and Indonesia and the so-called Bangladesh already gone ‘secular', there will hardly be an ‘independent' Muslim world left. This awesome scenario, God forbid, is too frightening even to contemplate. But surely it is not unwise to read the writing on the walls of contemporary history.

In the essay Beyond the Muslim Nation-States (1977), I pleaded for a new political science thus:

Muslim political scientists must now talk as a group of prisoners. They must define the scale and model of the prison in which they live. They must map the prison in detail. The three dimensions of this prison are social, economic and political. These dimensions are linked by intellectual corridors, of which the political scientists themselves are the leading exponents as well as victims. To plan and ultimately, execute an escape from this all-encompassing ‘open' prison, we may, for a while, have to behave like model prisoners and mix among our tormentors in a way that does not arouse their suspicion. To some extent it might even be possible to take the ‘guards' into our confidence. They might even cooperate with us so long as we do not become a threat to their positions and leadership roles in the short-term.

In essence the Muslim Institute set out to rescue Muslim political thought from its western and colonial embellishments and to put together a new paradigm of political thought that would sustain and support a future Islamic movement. As early as 1973 at Tripoli I sensed a new mood in the Ummah. One essential part of the plan was to ensure that the Muslim Institute inLondon was supported by Muslims from all ethnic, national, linguistic and cultural backgrounds. We were determined to ensure that the Institute we proposed would not be identified with any one ‘nation' or with Muslims from any one part of the world or with any one school of thought in Islam. The first step, therefore, was to secure support, and to raise funds. In pursuit of these goals, I travelled to the four corners of the world between 1973 and 1979. A year before the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the fledgling Muslim Institute moved out of my private study and into rented offices in Endsleigh Street.

Almost the first thing we did there in the summer of 1978 was to arrange a four-week course in Muslim political thought. The course was given by Dr Tayyib Zain al-Abidin of KhartoumUniversity. It attracted a cross-section of postgraduate students then doing research in London. Among them were a number of Iranian students. What became clear in the course of discussions was that, on issues of State and politics in Islam, there had emerged a consensus right across the Shi‘i/Sunni divide and the cultural and national diversity of the participants. This is precisely what we in the Muslim Institute expected would emerge from such an exercise. I was convinced that the consensus we had found was not a freak phenomenon in a small audience in the clinical atmosphere of London. My travels around the world and attendances at the ‘Islamic conferences' that were a feature of the 1970s, had convinced me that subtle but powerful processes were at work leading towards convergence in Muslim political thought. But the actual work of the definition and articulation of these processes of convergence, deep in the subconscious of a scattered Ummah, remained to be undertaken. This was the task that we were setting out to tackle. This was the invisible mountain that remained to be discovered, surveyed, mapped and, one day, climbed. An outline of the shape of this mountain that I guessed existed deep in the mist of history and in the subconscious of the Ummah is to be found in the Draft Prospectus of the Muslim Institute and in my two papers, Beyond the Muslim Nation-States and The Islamic Movement: A Systems Approach.

We did not know then that we already stood on the threshold of an Islamic Revolution that would reveal all before our eyes. The ‘big bang' effect of the Islamic Revolution in Iran is only just beginning to be realised. The Islamic Revolution was like a flash of lightning that revealed the full majesty of the future history of Islam. However, the same flash of lightning also blinded those who had grown accustomed to the darkness cast over them by the colonial and post-colonial periods. These blinded Islamic activists are now going round the world, their pockets bulging with Saudi petrodollars, denying that they had seen anything, or indeed that there was anything to see.

In London we rearranged our priorities. But first we invited Hamid Algar, professor of Persian and Islamic Studies at Berkeley, to give a course of four lectures on the Islamic Revolution. These lectures, held in July 1979, were attended by many of those who had attended the course on Muslim political thought a year before, and some 30 or so new faces. Algar's perceptive and erudite lectures were followed by lively discussions. In February 1980 Dr Muhammad Ghayasuddin and I visited Iran for the first anniversary of the Islamic Revolution. In August 1980 we took over the Crescent International of Toronto and relaunched it as the “newsmagazine of the Islamic movement.” In 1981 we launched the Muslimedia news and feature service, and began to publish the annual anthology, Issues in the Islamic Movement. We had thus created a journalistic and publishing base mobilizing resources in London, Toronto, Pretoria and Kuala Lumpur. I then began my second round of extensive tours to distant lands, talking now about the Islamic Revolution. This included frequent visits to Iran, where my non-Iranian and Sunni understanding of the Revolution was often at variance with the Iranians' own perceptions. We knew then, as we do now, that the Islamic Revolution would have to be conceptualised in a “grand strategy” and an “overarching” theory capable of sustaining a global programme of Islamic Revolutions.

It is to this task that we applied ourselves at the academic level. Our chief instrument was the annual world seminar held in London from 1982-1988. These seminars attracted Muslims of all schools of thought, including leading ulama, and Muslims of all ethnic and geographical origins and social and cultural backgrounds. Many of them were students and academics I met on my travels, and many were attracted by our coverage of current affairs in the Crescent International. Many of the chapters in this book were first written for these seminars. The justification for the title of this book is that the political ideas presented here have been found acceptable at world seminars held in London and to a wider audience in all parts of the world. I have no doubt at all that these ideas, at least in outline, represent the overarching theory and grand strategy of the political thought and action of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, of themujahideen in Afghanistan, of the Hizbullah in Lebanon, and of the revolutionary Islamic movement that is taking shape in all parts of the world. These ideas have also penetrated deep into the ranks of al-Ikhwan al-Muslimoon and Jama‘at-e Islami. The ‘moderate' leadership of these parties will find it increasingly difficult to hold their position of seeking change through ‘democratic' processes within the framework of the post-colonial and secular nation-States. Recent events in Iran, Afghanistan and Lebanon, and the oppressive measures against the Islamic movement taken by the west's client regimes in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, Algeria, Morocco, Pakistan and Indonesia are evidence, if evidence were needed, of the return of the political power of Islam as a major factor in world politics. The fact that the political power of Islam is now a major factor in world politics is also confirmed by the reaction of those whose interests are adversely affected. This was most blatantly obvious in the way the US, the Soviet Union and their respective clients in Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere collaborated to deny Iran a military victory over Ba‘athist Iraq. Their massive military and diplomatic intervention prolonged the war by five years, while their propaganda accused Iran of not accepting a cease-fire. A similar collusion between the US, the Soviet Union, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia produced the ‘Geneva Accords' on Afghanistan. The sole purpose of these accords was to save the Soviet Union's face as a ‘superpower' that had been militarily defeated and to present the Soviet ‘withdrawal' as an act of magnanimity. The ‘human rights' lobby in the US and Europeremained largely silent over the deaths of l.2 million Afghans, the suffering of five million refugees, and the wanton destruction of the Afghan countryside by the Soviet use of chemical weapons. In Lebanon the Hizbullah fighters inflicted massive military defeats on the ‘peace-keeping' forces of the US, Britain and France and upon the Israeli army of invasion and occupation.

The political power of Islam that is now a major factor in world politics is fundamentally different from the earlier manifestations of Islamic power. For nearly 1,300 years, from the beginning of Banu Umaiyyah's rule in 661CE to the abolition of the Uthmaniyyah khilafah (Ottoman Empire) in 1924, the political power of Islam was gradually corrupted and exercised by dynastic rulers. Two of the essential characteristics of political legitimacy were missing throughout this period, with the exception of the brief rule of Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (717-721CE). These essential features are taqwa (piety) of the ruler and the voluntary bai‘ah (allegiance) of the people. Throughout this period allegiance was imposed upon or extracted from the people, and hereditary succession took little or no account of the ruler's fitness to rule. Nevertheless the initial momentum generated by the power of Islam was so great that, despite subsequent deviation, the domain of Islam expanded and remained dominant over a large part of the world. This dominance also gave rise to a worldwide Islamic civilisation. All earlier civilisations, such as those of China, India, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Greece, had been limited both geographically and in the shadow they cast over subsequent history. The Islamic civilisation was unique in that it was the civilisation to become global.

In the last 200 years a new secular civilisation has been developed and imposed on the world through western political and economic domination, and scientific and technological advancement. The west claims that the secular civilisation represents the primordial nature of man. The civilisation of Islam is also based on an equally emphatic view of the primordial nature of man. To the west, Islam's claim to represent the ‘nature of man' is little more than unscientific dogma and superstition. To Islam the world and the universe are a deliberately created system. To the west there is no single source of moral values beyond man's own rationality. Islam asserts that Allah, the sole Creator of the universe and all that is in it, is also the sole source or moral values of good and evil. To the west, good and evil are relative terms forever changing according to the moods, fancies and requirements of man, as determined by his own reason and self-interest in the pursuit of happiness. In Islam happiness is attained through the worship of Allah and commitment to eternal moral positions laid down by the Creator.

In short, two global civilisations, both claiming to be in accordance with the primordial state of nature, are now engaged in a titanic struggle. Until recently the secular civilisation believed that it had already secured unchallenged and unchallengeable supremacy. The west's political domination, economic growth and scientific and technological advances gave the secular civilisation the appearance of permanence and invincibility. This was reflected in the arrogance of western historians, philosophers, scientists and statesmen. They assumed that the defeat of the political power of Muslim rulers would in turn lead to the total disappearance of the Islamic civilisation as well. They began to deal with Islam and Muslims as a subservient culture and civilisation; they began to hold patronising ‘festivals of Islam' and exhibitions of ‘Islamic art.' They reduced Islam to a place of honour in their museums. If they acknowledged the greatness of the Islamic civilisation at all, it was only to assert how much greater were the achievements of their own secular civilisation.

In the matter of political power there is a fundamental difference between the Islamic civilisation and the secular civilisation. It is true, of course, that the primacy of political power in Islam is central and unquestionable. The first Islamic State was set up by the Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace, himself and he was also the head of that State; therefore the State is an integral part of the revealed paradigm of Islam. It can be argued that Islam is incomplete without the Islamic State. Political power, therefore, is an essential component of the Islamic civilisation. The quality and quantity of political power exert a great influence on the Islamic civilisation. During the 1,300 years from the beginning of the Umaiyyad period to the end of theUthmaniyyah khilafah, the political power of Islam expanded greatly and brought even larger areas of the world under its control. However, during the same period the moral stature and Islamic legitimacy of political power declined continuously. Eventually the process of moral decline inaugurated by Banu Umaiyyah reached a stage where the political power exercised by Muslim rulers was little different from the political power of non-Muslim rulers. The greatly weakened and corrupted political power of Muslim rulers was no match for the newly-emergent political power of the secular civilisation that had sprung up in Europe. In a short time the political power of the secular civilisation had defeated or otherwise overcome the deviant and corrupt Muslim rulers and their States and empires. The European powers persuaded themselves to believe that they had overcome the political power of Islam itself; that Islam in its political manifestation had been eliminated for all time to come. The reality was very different. Although the victory of the European powers left Islam without a State, the civilisation of Islam had not been destroyed. Because Islam is the state of nature, every part of it is capable of regenerating all other parts. It was, therefore, only a matter of time before the residual Islamic civilisation regenerated the political power of Islam.

The processes by which a civilisation, or parts of a civilisation, are regenerated are little understood in any system of thought. In the social sciences of the west there is a good deal of concern with change and conflict. Most social sciences are a study of the processes of change and resistance to change on the margin of an established order. Equilibrium and stability are achieved through adjustment and accommodation between forces for and against change. If change takes place in a legal-rational framework of consensus politics, the society is said to be stable. In this secular ‘scientific' framework no judgement is made about whether any particular change is good or bad, desirable or undesirable. All that is required is that the law should not be broken (the law can be changed to avoid its being broken), and that ‘public opinion' is suitably prepared to accept or adjust to change without resort to violence. Such a society claims to be ‘progressive' and developed if equilibrium and stability are also achieved at a time of economic growth and rising material standards of living. Should this also be accompanied by diplomatic and military successes in foreign relations, the society is more likely to be counted among the ‘advanced' and ‘powerful' nations of the world. All those nations that are‘advanced' and ‘powerful' in this sense make up the modern secular civilisation. Political systems that are part of the same civilisation often fight each other. Some are defeated, others are victorious. After each war the victorious help to rebuild the vanquished, such as Germany and Japan after the 1939-1945 war. The US also helped to rebuild all of western Europe through the Marshall Plan. In this case it is also important to note that not all centres of political power in the secular civilisation had been destroyed by the war. Having crushed the sources of ‘evil' in Germany, Japan and Italy, the surviving centres of political power cooperated to rebuild all parts of the secular civilisation. The Soviet Union played a similar role in rebuilding Eastern Europe. Whatever their differences, the fact is that the Soviet Union and the US, and their respective allies and client States, are parts of the same modern secular civilisation.

The secular civilisation has never faced the crisis of the destruction of all centres of its political power. Only the Islamic civilisation has suffered the total destruction of all centres of political power. The process did not stop there; it went further. The secular (western) civilisation imposed itself on all Muslim areas of the world. The lands and peoples of Islam were divided into new centres of subservient political power. The colonial powers imposed the secular civilisation on Muslim areas and divided them into new nation-States under their control. These new nation-States that emerged in the Muslim world became instruments of the secular civilisation. In this way the centres of the political power of Islam were not only destroyed but also replaced by numerous other centres of secular and subservient political power. This made the regeneration of Islam's political power doubly difficult.

Other factors added to these difficulties. The most crucial of them was the absence of descriptive and analytical political thought from the massive intellectual industry of the Muslims in such other fields as mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, geography and general philosophy. Some explanation for their blind following of the khilafah, even when in substance the khilafah had deviated beyond recognition from its origin among the first four khulafa, the khulafa al-rashidoon, must be offered. This blind spot in the otherwise extensive and profound Muslim intellectual tradition becomes even more incomprehensible when the example set by Imam Husain in challenging the legitimacy of Yazid, the second ruler of the Umaiyyad dynasty, and paying the supreme price at Karbala, is taken into account. Many explanations can be and indeed have been offered. The Muslim problem remains that, without a paradigm of political thought that describes and explains the present political situation, we cannot even begin to work towards the regeneration of Islamic political power.

However, political thought always reflects the existing political reality. This point is well illustrated by the nature of the political thought that emerged among Muslims during the colonial period. Under the influence of colonialism, Muslim thinkers adopted western political ideas and dressed them up as the political thought of Islam. Powerful political systems invariably have a considerable influence over intellectual activity and climates of opinion in their areas of control. The British model of parliamentary government exercised almost universal popularity during the heyday of the British empire. More recently the US presidential model has been in vogue. In areas under Soviet ‘communist' domination the Russian model was until recently preferred. This is true not only in the matter of government and constitutional structures; in the matter of political Organisation the same relationship has been in evidence. The Muslim political elites of the colonial period were in any case bound to pursue the nationalist/secularist path of their European mentors through political organisations with roots in the European political systems. Thus the political party model of Organisation came to hold such sway that even those who tried to organize an Islamic challenge to secular orthodoxy ended up forming European-style political parties. Muslim political thought and behaviour became trapped in a bog-like patch of history in which the only firm ground under Muslim feet was western in origin. The solid political ground of Islam had slipped out of reach. The regeneration of Islamic political power seemed improbable, if not impossible. The secular civilisation and its major centres of political power in North America, Europe, the Soviet Union, Japan. Israel and India had taken all necessary steps to ensure that the political power of Islam would not raise its head again.

For Islam this was a grave crisis. The total absence of political power was not only a ‘political' question. It was not a question of choosing a form of government, or choosing between democracy and dictatorship, capitalism and communism. Every available option was part of the new global secular civilisation based on kufr. As Islam is Allah's own choice for mankind, and the model has been completed with the prophethood of Muhammad, upon whom be peace, Islam must regenerate its political power. If Islam is the embodiment of Divine Wisdom that transcends all stages of history—past, present and future—then it must also provide for the regeneration of its lost and destroyed political power. Indeed, if political power exercised by the Islamic State is essential for the fulfilment of the Divine Purpose, then Islam must also have the resilience necessary to recapture its original condition in vastly different historical situations. In short, to be valid, like a scientific experiment, Islam must repeat itself. However, unlike a scientific experiment, in the process of repeating itself it must also be able to deal with and take into account new factors and situations vastly different from those that were present when the model was first completed.

One such difference can be noted immediately. The first model was completed by a movement under the leadership of the Prophet, upon whom be peace, who was guided by Divine Revelation. To repeat the model 1,400 years later would involve doing so without prophethood and revelation. Their obvious replacements are muttaqi leadership and ijtihad. To replaceprophethood and revelation, the leadership's taqwa, competence and capacity to engage in extensive ijtihad must be of the highest order. The new leadership will have to have a deep sense of commitment to the step-by-step regeneration of the political power of Islam. The leadership, through its taqwa, sense of history and ability to engage in ijtihad, should also be able to unite the Ummah. The regeneration of Islam's political power can make no sense without a comprehensive approach to the unity of the Ummah. A divided Ummah cannot regenerate the political power of Islam. A partial regeneration of political power, based on a geographically limited area, will not meet the minimum requirement of repeating the original model. Any failure to take into account the fact that the Ummah today is global, comprised of 1,000 million Muslims, and that the power of kufr that has to be defeated now is also global, will compromise the validity of the model.

The original model at Madinah had to defeat the power of kufr, which was then local, or at best regional, and there were not vast disparities in levels of technology and economic performance. In the contemporary situation the secular civilisation, or kufr, is globally organised in a world economy and inter-linking political systems. Islam, therefore, has to repeat itself in a vastly more complex world than existed 1,400 years ago. This difference between the two historical situations has to be bridged by muttaqi leadership and ijtihad in place ofprophethood and Divine Revelation in the original model. It has always been my position that the Islamic Revolution in Iran represents a major step in this direction. In Iran the leadership of the ulama, especially of Imam Khomeini, and a continuous ijtihad, have produced results that, if repeated in other parts of the world of Islam, would lead to a global Islamic Revolution. For the new model in Iran to achieve and command full historic validity, it must also have the capacity to lead the Ummah and to generate, by force of example and leadership, similar Islamic Revolutions in all parts of the world. Islam has no frontiers and Islam in one country makes no sense. A programme of Islamic Revolutions in one Muslim country after another offers the only way forward.