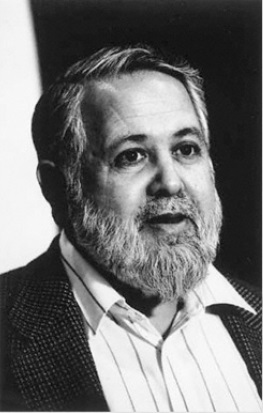

Iqbal Siddiqui

Iqbal SiddiquiLike most visionaries and revolutionary thinkers, Dr Kalim Siddiqui, who passed away on April 18, 1996, was far ahead of his times.

“The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long that nation will begin to forget what it is and what it was... The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” (Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, 1979.)

These eloquent lines were written by a Czech novelist reflecting on the Soviet communist assault on his people’s literature and culture. But they express a universal truth experienced by many peoples in many contexts throughout history. Not only is history written by the victors, but all previous or alternative versions of history, and the cultural memories on which they are based, are disparaged, marginalised, subtly distorted or simply eliminated. The process is often thought of as one of historical self-justification on the part of victors, but usually goes deeper than that. Almost invariably, it also involves a deliberate, manipulative process of re-defining the present and so shaping the future.

In the Muslim world in the modern era, the most obvious example is the destruction of the Ottoman heritage by Mustafa Kemal’s aggressively westernising regime in Turkey. This was made possible first by the destruction of the traditional, Islamic intellectual elite in the 1920s, and even more so by the change in the Turkish script which made centuries of Ottoman intellectual work incomprehensible to most Turks. But many other Muslims have suffered similar assaults, in the communist ruled areas of Europe and Central Asia, or at the hands of other aggressively secularising regimes in post-colonial nation states elsewhere. The creation of ‘national’ identities, histories and movements in territories defined only by administrative imperatives of the colonial powers is just one example. Many others could be cited for each and every Muslim country in the world, and every Muslim community living under non-Muslim rule anywhere in the world.

Nor is this process of rewriting and manipulating the collective memory of peoples a purely historical one. The issues of ‘fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’ have suddenly been discovered by western liberal elites since the success of populist political movements such as those exploited by Donald Trump in America and the anti-European ‘Brexit’ movement in Britain, but they are hardly new. They are simply the exploitation in western domestic politics of techniques of political propaganda and cultural-social-political manipulation that western elites have long used in other countries. Western liberals who now bemoan the use of false narratives to mobilise support behind Trump have themselves used precisely the same methods to bolster their own positions, and have supported or condoned the use of the same methods by western elites and their allies to pursue their interests in other parts of the world.

Examples are legion, in both Muslim and other countries. The false narrative created over the zionist colonization of Palestine is an obvious one, although one that is at least effectively countered thanks to the resistance of the Palestinians, the tireless solidarity of Muslims around the world, the goodwill of many other supporters, and the sheer effrontery and brutality of the zionist state, which has alienated many who might otherwise have supported it.

But many other examples are less recognised, and have been so successful that even many Muslims whose instincts are anti-western and anti-imperial are influenced by them. One such is the concerted rewriting of the history of the so-called “Arab spring” to demonise Islamic movements, such as the Ikhwan al-Muslimun in Egypt, to justify the repressive policies of authoritarian regimes, and to justify Western support of such regimes in the name of the ‘war on terror’. In this case, the Ikhwan did everything demanded of Islamic movements in terms of using ‘peaceful’, ‘democratic’ means of achieving power, and yet were quickly and brutally overthrown amidst a campaign of propaganda to prevent them disproving the lie that Islamic movements are bound to be unpopular, repressive and incapable of governing effectively.

Another is the characterization of the still-ongoing war in Syria, many understandings of which are defined by the western-dictated narrative of a popular uprising against a dictatorial regime backed by Iran and its regional allies. This narrative, supported by a long-nurtured sectarian narrative pitting Sunnis against Shi’is, has achieved general acceptance despite the fact that the war is in fact yet another chapter in the long proxy war being waged by the US against Islamic Iran and the ‘axis of resistance’.

In the same context, we see also the long-standing and well-established propaganda about Iran’s nuclear program. This has been used to both divert attention from, and justify when necessary, the US’s widely known but little discussed covert war against the Islamic state, which has included political interference, terrorism, economic warfare, technological attacks and assassinations, and which is still continuing behind the cover of the so-called nuclear deal agreed in 2015.

And to find an example beyond the Muslim world, we also have the politicking over the crisis in Ukraine, deliberately created by western powers when the country’s democratic government decided against an alliance with the European Union, but portrayed across the international media as an example of aggressive Russian expansionism.

These are, of course, big international issues of global geopolitical import. But similar strategies of propaganda and political misinformation are used at every other socio-political level down to the most local, creating interlinked false narratives of every kind, all serving – by design or effect – the same agendas of western domination and the marginalization of dissident voices.

To take just one example, we can look at the life, work and posthumous profile of the late Dr Kalim Siddiqui, with particular reference to the development and history of Muslims in Britain. He was a significant figure in British Muslim affairs from the 1970s onwards, as director of the Muslim Institute for Research and Planning. For almost two decades, from the Islamic Revolution in Iran to almost the end of the Bosnian war, through a crucial period in Western-Muslim relations, including the first Gulf War and the US occupation of the Arab heartlands of Islam, Dr Kalim’s was the dominant Muslim voice in British affairs, and an important one internationally. The Muslim Parliament of Great Britain that he established after the Rushdie imbroglio, and led until his death, had a massive impact at the time, provoking an establishment reaction that has shaped official British policy towards the Muslim community ever since.

And yet, like so many other Muslims around the world whose views and approaches are regarded as dangerously subversive by those in power, his work was both misrepresented and disparaged at the time, and subsequently written out of history in order to minimise their continuing impact and influence. In the many discussions of British Muslims in the media and academia in the 21 years since his death in April 1996, across a period when the position of Muslims in Britain has come under extreme scrutiny for obvious reasons, Dr Kalim and his work have seldom been given more than passing reference. Far more attention has been given to figures and institutions whose roles were less challenging, and therefore more acceptable, to the powers that be. And tragically for British Muslims now, even many Muslims have been misled by this deliberate marginalisation of a figure whose example and model could have offered so much in the current situation.

None of this would have surprised him, of course. An awareness of the nature and role of western academic and media institutions, honed by experience of working in both, was central to his work. In the paper ‘Beyond the Muslim nation-states’ (1976), he had critiqued western historical writing and social sciences. The establishment of the Muslim Institute was intended both to provide an alternative understanding of the history of the Ummah, and to plan for its future; one of the first academic committees it established was a history committee. As the Institute’s work on histories past and future were overtaken by contemporary events with the Islamic Revolution in Iran – events that Dr Kalim had predicted but did not expect to see in his lifetime – he had overseen the conversion of Crescent International to a ‘newsmagazine of the Islamic movement’ precisely in order to challenge the western domination of the international media in a pre-internet age. Later he would establish the Muslimedia news syndication service for the same purpose, as well as supporting numerous other Islamic media projects in Britain, Pakistan and other parts of the world. And all the same themes loom large again in his final book, Stages of Islamic Revolution (1996), written and published shortly before his death.

Twenty-one years later, Crescent International remains almost the only functional part of his legacy, the rest of the institutions he founded having folded under pressures internal and external, although the direct and indirect influence of his work remains strong in many areas. The world in which Crescent operates has also been transformed, by the technological advances of the digital communications and information revolutions, the intensity and brutality of the west’s war on Islam since 9/11, and the complexities of the socio-political strategies put in place to manipulate Muslim societies and movements as part of that war.

Such is the pace of developments in the modern world that Dr Kalim must now be regarded as a historical figure rather than a contemporary one, alongside such notables in the history of the modern Islamic movement as Imam Khomeini, Shaikh Hassan al-Banna, Maulana Maududi, Syed Qutb, Ali Shari’ati, Mohamed Iqbal, Muhammad Abduh, Muhammad Asad, Aliya Izzetbegovic, Abdullah Azzam, Shaikh Omar Abdul Rahman, and Shaikh Ahmed Yassin, stretching back perhaps to Jamaluddin al-Afghani, and including many whose names are long forgotten, if indeed they were ever known at all. But to say that is not to minimise his importance, for an understanding of the ideas and contributions of all these many and varied figures is essential for contemporary Muslims to understand the world they are living in, the historical situation and challenges they face, and the Islamic movement of which they are a part.

The western domination of the information and media landscape is not the only obstacle to Muslim understandings of their own history and circumstances, of course. Another major one, which Dr Kalim was well aware of, is the fact of being constantly under attack, overwhelmed by the need to react to current events. This is a situation hardly conducive to reflective thought and long term planning, for those fighting for their lives, or under an unrelenting onslaught of abuse and propaganda, and so concerned primarily to defend themselves and survive in the here and now, are unlikely to be able to find the time and space necessary to contemplate their yesterdays and lay the groundwork for their tomorrows. Keeping Islamic movements of all levels permanently on the defensive is undoubtedly one of the key elements of the west’s intense current war on Islam.

The understanding that these different levels of work are inseparable, and the ability to work on so many of them simultaneously, was one of Dr Kalim’s great contributions. But the variety and conflicting pressures of his different projects may have led to their being misunderstood and under-appreciated. Certainly the different imperatives of the Muslim Institute’s global perspective and intellectual work, and the Muslim Parliament’s local focus and practical community work, contributed to the tensions that destroyed both after his death.

Nonetheless, his emphasis on the importance of understanding history, both past and present, and on the necessity of reflective intellectual work even in the face of immediate challenges, provides lessons and models from which Muslims today could learn so much. As we struggle against power, and if we are to remain who we are supposed to be, instead of becoming what our enemies would like to make us, it is essential that we maintain control over our own history, through both the awareness of the nature and stratagems of our enemies, and the memory of the struggles and achievements of men such as Dr Kalim Siddiqui. Recognizing what our enemies would like us to forget, and ensuring not only that we remember it, but also that we learn from it, is perhaps, as its broadest level, is the real challenge facing us and our future generations.

[For more comprehensive information, you can visit www.kalimsiddiqui.com which is being developed as a permanent record of the work of the late Dr Kalim Siddiqui (1931-1996)]