Yehia Amin

Yehia Amin The history of Islam in China is complicated by the existence of many Muslim ethnicities. Some have been there since the beginning of Islam itself; some settled as merchants, and others came as a result of conquests by the Mongols and the Qing Dynasty. The Chinese flag, which has five stars, reflects these ethnicities: one large star symbolizes the Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group associated with the “Chinese people” and four minority races: Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan, and the Hui.

Sometimes the designation of Hui is used to subsume all Chinese Muslims. Often the word Hui refers to the specific ethnicity of the Hui. This means that the Uyghurs of East Turkistan, Salars, Muslim Mongols, and other Muslims do not count under this term. The modern usage of the term Hui stems from Chinese Communist Party (CCP) publications dating back to 1941.

Who are the Hui? They are an ethnic group closely linked to the Han majority in culture, but not religion. In fact, the Hui are one of many groups inside and outside China that adapted the philosophy of Confucianism to their own needs as a religious community. This formal synthesis of Islamic and Confucian learning in the Hui community is called the Han Kitab, and its writers seek to emphasize the similarities between Islam and Confucianism in order to accommodate officials training in the Chinese bureaucratic system, who did not want to abandon their Islamic learning.

In multi-ethnic regions, the Hui have acted as mediators between local non-Hui Muslims, and the Han. The Hui are considered “the most urbanized ethnic minority group in China.” The place of the Hui as mediators between Islamic identity and “Chineseness” follows a long and complicated history. How can the persecution of Uyghurs in East Turkestan/Xinjiang happen when another Muslim minority is so widespread and more or less harmonious with the Han majority?

Hui history started almost as soon as Islam began. Arab, Persian, Turkic, and Jewish merchants and sailors settled in coastal cities such as Guangzhou in eastern China starting around 651ce. According to legend, the Prophet’s maternal uncle and companion Sa‘d ibn AbiWaqqas travelled to China to meet the Tang emperor. Sa‘d’s stay in China is important as a founding myth for the Hui, but according to some writers, little evidence exists to prove his presence. The period of early Hui history is seen more as a legendary beginning of the Hui community in China. While seemingly mythical, the early history does contain seeds of truth that set precedents as to how the state treats the Hui.

The practice of dividing the local Muslim community leadership among the shaykh, qadi, and secular chief comes from imperial regulations imposed by the Tang imperial authority on the settled Muslim merchants. The real root of Muslim presence in China comes with the Mongol invasion and establishment of the Yuan dynasty.

The Mongol invasions necessitated soldiers, artisans, administrators, and scientists to consolidate new territories. The Mongols did not have experience in these fields, so they frequently turned to subjugated peoples. Amongst the subjugated peoples were many Muslim populations in Central Asia: Turks and Persians. These populations were relocated across China to serve the Mongols as they built the Yuan dynasty, officially established in 1271ce.

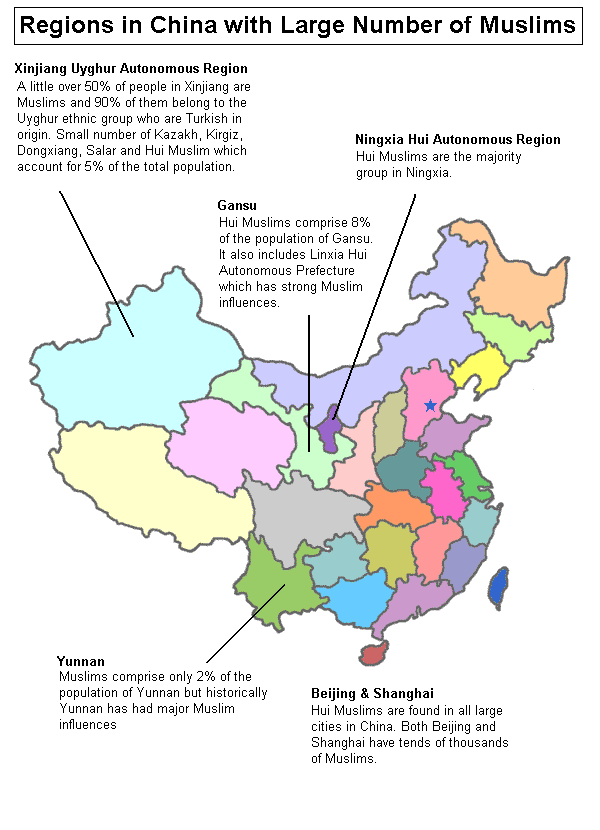

They settled in China with their families in almost all corners of the country. This widespread settlement of the Muslims persists today as the Hui can be found in every province across China. Muslims even contributed to the Sinicization (the cultural conversion of non-Chinese peoples into Han values) of frontier provinces such as Yunnan. Muslim families intermarried with Chinese families, and conversions are known to have occurred. In the Mongol racial hierarchy, they placed Muslims above the local Han. This did not come back to haunt the new Muslim population so much when Chinese rule was re-established with the Ming dynasty.

In 1368, the Mongols were chased out of mainland China by the Hongwu Emperor, the first of the Ming dynasty. The new Ming emperor did not turn his wrath on the Muslims after his successful coup, probably because Muslims chose to fight in support of the rebellion against the Yuan. He did however close China’s borders to the outside world, cutting off the yearly Hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah) and scholarly networks that connected Chinese Muslims to the rest of the Muslim world.

This meant that Chinese Muslims had to rely on what they had within China. In the later Ming dynasty, Jesuits started to preach Catholic Christianity to the Chinese using a top down approach. This meant that the Catholicism preached was highly Confucianized and aimed at scholars in the hope that the lower classes will follow into Christianity after the scholars’ conversion. The Jews of China also followed and started to write about the compatibility of Jewish thought to the Confucian way.

Muslims turned to Arabic and Persian literature available in China and worked toward writing about Islam in Chinese using these texts as sources. Schools called Scripture Halls were established to teach this Islamicized Confucianism to potential bureaucrats and imams. Students were taught to read Chinese, Arabic, and Persian alongside Islamic and Confucian curricula. Because the Hui had a limited number of books across Sunnism, Shi‘ism, and Sufism, the Han Kitab represents a patchwork of Islamic intellectualism that is unseen in most of the Muslim world. Only two of these figures have been translated into English: Wang Daiyu and Liu Zhi.

In the Qing era (1644–1912), the development of Han Kitab continued, but divisions amongst the far-flung communities started to develop. While Sufi books had existed in China for a while, the arrival of formalized Sufi orders created a strain between communities. The Hui considered the Sufi orders to be part of a new sect, despite the earlier presence of Sufi books. The arrival of Wahhabi-influenced scholars, and later actual Wahhabism, caused further fractures in the community.

The salafized sect known as the Yihwani and the Wahhabis rejected the use of Chinese and Persian materials in the teaching of Islam. As a reaction to the Wahhabis and the Yihwani’s rejection of non-Arabic literature, a sect emerged that took the Han Kitab writings as the ultimate source for the Hui interpretation of Islam. These sectarian divisions reflected how geographically far flung the community was. In some regions like Yunnan, these sectarian splits did not influence the local Hui.

As imperial power broke down in the late Qing, wars, rebellions, and massacres occurred across China. The “frontier” regions were most associated with this era of violence. Muslims were involved and victimized in various raids, rebellions, and bandit attacks in the northwest.

This era culminated in the atrocities of Japanese occupation in the east of China. Muslim warlords already held power at this time and helped to rally support against the Japanese occupiers.

After World War II, Muslims were split between the republican democrats and Mao Zedong’s communists. Eventually the communists won over the postwar Muslim leadership. The Hui’s fate under the Communist regime is a long story in and of itself that needs to be addressed separately.

Muslims in Imperial China were integrated into “Chineseness” that may remind one of Islam in India or Andalus. Unlike India and Andalus though, Muslims were not the ruling power. The Hui offer an example of how Muslim diaspora communities in the West can hold on to their Islamic identity while living among non-Muslims. Just like the Hui, Muslims in the West are geographically spread out, and actively translating Islamic concepts and texts into non-Islamic foreign languages. Some of us are besieged by sectarian divisions, and the threat of violence. For Muslims, Confucianism could be a valuable tool as a philosophical system that can function as an alternative to secularism.

Confucianism can provide Muslims today with a tool of decolonization and empowerment. Understanding how a Muslim school of Confucianism exists, we should attempt an evaluation of its philosophy. The benefit of having a working alternative to secularism that brings the community’s intellectualism closer to East Asian thought is invaluable, especially as China grows more powerful on the world stage. The value of Confucianism to the contemporary Islamic world will be discussed in a future article, insha’ Allah.

Yehia Amin is an independent scholar specializing in Islamic and Chinese philosophy. He has an MA in Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations from the University of Toronto. He is learning Mandarin in the hopes of translating Confucian philosophy into Arabic.