Hajira Qureshi

Hajira Qureshi

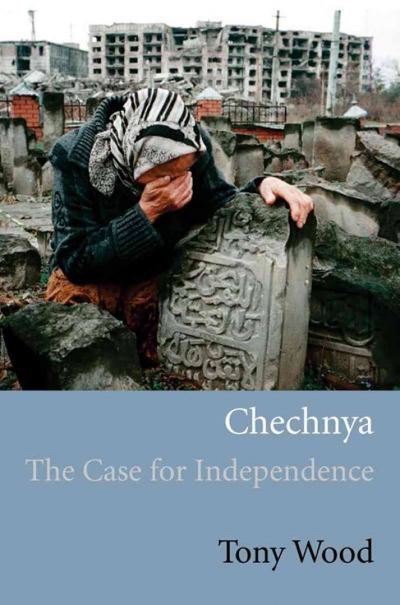

Chechnya: The Case for Independence by Tony Wood. Pub: Verso Books, London, UK, 2007. Pp: 199. Pbk: £12.99.

Discussions on the situation in Chechnya often follow the line of the humanitarian, human rights or political disaster that it has been for the last thirteen years. But what is the root of all these problems? Surely it is the Chechens’ lack of independence. After all, that is what the Chechens have been struggling for for the last 400 years. The Chechens have time and again asked, demanded and fought for their freedom. And why is Chechnya held to be ineligible for statehood? Many arguments have been put forward byRussia and its allies: realpolitik about Moscow not accepting it, or that the West must not antagonise Russia, or concern aboutEurope’s energy supplies. Some, even in the Chechen camp, say that Chechnya had its chance at independence in the period from 1996 to 1999 but performed woefully. Others just shake their heads and ask how the ideal of independence can still be alive in the mess that is Chechnya today.

This book, written by Tony Wood, a well-known campaigner for the Chechen cause in the UK, aims to lay out a comprehensive case for Chechen independence. As he says in his introduction, many books have examined North Caucasian history in detail, but few have addressed the issue of whether or not the Chechens have a right to a state of their own. Wood argues that they have and in fact that “their right to govern themselves should be the starting point for any discussions” on Chechnya – not a point, as is usually the case, that is barely mentioned or heeded.

The book begins with the Chechen proverb “Nokhchi khila khala du”, “it is hard to be a Chechen”, a sentiment which is only confirmed in the reader’s mind as he or she reads on. The first chapter describes the Chechen experience in detail and how “as a nation the Chechens have been forged under the hammer-blows of history”. He compares the history of the Chechens with the history of the other North Caucasian peoples: the Circassians, the Balkars, the Kabardins, the Ingush and the Ossetians, for instance. He explains how these people differed from each other not so much because of different languages or cultures but because of their varying experiences of foreign domination. In contrast to most other North Caucasian peoples, the Chechens have an almost unbroken record of struggle against foreign rule, be it by the Cossacks, the Tsars, the Soviet Union or contemporaryRussia. The reasons for this, among others, Wood says, are topographical and demographical; only in Chechnya do we find dense forests that make guerrilla warfare possible, and Chechens have always been the most numerous of the North Caucasian people, thus providing the large numbers of foot-soldiers needed for any rebellion.

In the first chapter the author takes us from the late eighteenth century to the deportations of 1944, illustrating how the experiences of conquest, colonisation and rebellion added to these features of Chechen society. Above all, Wood argues, it was the Stalinist deportations of 1944 that “became the defining event in Chechen national consciousness”.

The second chapter opens with the observation that the deportation proved to the Chechens that they could only be safe in a sovereign state of their own; the two recent Russo-Chechen wars only confirm this. Here, we are taken from the fall of the Soviet Union to the Chechen Revolution of 1990-1, through to Dudaev’s election and declaration of independence on 1 November 1991. At the fall of the Soviet Union, many ex-Soviet states declared independence in the years 1990-91: Lithuania, Armenia, Georgia,Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. However, the subsequent experiences of these states and Chechnya were strikingly different. The rest of them gained independence and UN membership; Chechnya had to face over a decade of war and repression, which have left the people traumatised and the country almost destroyed.

Here Wood takes us through the politics of secession and how Chechen secession should be viewed under international law. There is a balance, he states, in international law between the principle of self-determination and the preservation of territorial integrity. In December 1960 the UN passed a resolution which states that all people subject to colonial rule have the right to “freely determine their political status”. However, such noble ideals are, at the behest of certain governments, set aside for realpolitik, as has been the case for Chechnya. In Chechnya, as Wood concludes his second chapter, “a broadly legitimate and constitutional secession went unrecognised because it ran counter to the interests of Russia, a Security Council member …”

In the third chapter, Wood deals with Yeltsin’s war from 1994 to 1996 and the rationales offered for it; one by one he shows each to be completely baseless. In December 1994 the incursion into Chechnya was announced as an operation to “restore constitutional order”. Russia “needed” to reign in a rogue enclave to restore rule of law and maintain Russia’s territorial integrity. Moreover, Yeltsin needed a “small, victorious war” to improve his ratings. But Moscow did not succeed in any of its goals, stated or otherwise. The war was a humiliating defeat for Russia, the outcome of which, the Khasavyurt Accords, signed on 31 August 1996, recognisedChechnya as a subject of international law, thereby implying de facto Russian recognition of the sovereignty of Chechnya. When Yeltsin signed the “Treaty on Peace and the Principles of Interrelations Between the Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic Ichkeria”, he signed the end of 400 years of hostilities and recognised Aslan Maskhadov as Ichkeria’s president.

Wood goes onto illustrate how baseless is the argument, put forward by Russia, that if Chechnya succeeded in its secession this would lead to a chain of separatist movements in the rest of Russia. Going through economic, geographic, demographic, Islamic, ethnic and geostrategic considerations, he discounts each one and clearly demonstrates how the “domino effect” was always extremely unlikely. Here Wood mentions the international community for the first time, commenting on its acquiescence and complicity; the West preferred free-market capitalism over democratic prerogatives, and regarded Chechnya as the price for capitalism to flourish in Russia.

In chapter four Tony Wood discusses the three years (1996-99) in which Chechnya had de facto independence and what became of the tiny country in this time. He begins by stating that Chechnya is portrayed as a “lawless land blighted by crime and religious extremism” and that it is dismissed as a “failed state”, so Russia was entitled to “bring it into line” by invading it in 1999. But, he argues, Chechnya was an extremely damaged nation as a result of the 1994-6 war. There was no infrastructure left; much of the arable land was destroyed; the economy was virtually non-existent; its people were traumatised; many children were being born with birth-defects; infant mortality was high; Grozny had been bombed into the Middle Ages; there was little employment or housing; the list goes on. He maintains that it would have been an impossible task to turn Chechnya into a peaceful and happy country in those three years, even if there had been ample international aid and support. As it was, no country chose to recognise Chechen independence or to assist Chechnya with loans or aid. Most of the aid promised by Russia was embezzled en route. Despite signing several treaties, Moscow worked assiduously to undermine both the Chechen state and the leadership of Maskhadov. Wood shows the reader that it was a completely hopeless situation and that no one could have done any better in circumstances such as these. In its depiction of Maskhadov’s helplessness, this chapter is the most heart-wrenching in the book.

Next Wood analyses and exposes Putin’s war, once again begun, ostensibly, to “rein in the lawless periphery”, protect Russia’s territorial integrity, and fight “Islamist terrorism”. He argues that none of these “remotely account for the terror that was unleashed on Chechnya”. He talks us through the fact that Putin broke several treaties when he went to war with Chechnya and that it “became rapidly clear that the civilian population was the real target of the ‘anti-terrorist’ operation”. The military stalemate and the degeneration of the Russian army, where more than half of the Russian deaths were in non-combat situations, meant that the mortality rate of Russian soldiers was high. This led to Putin’s policy of ‘Chechenisation’ of the conflict: the appointment of the puppet Kadyrov as head of a pro-Moscow administration, the rigged referendum to pass the new constitution, in which Chechnya was declared part of the Russian federation, and the formation of a Chechen militia, the kadyrovsty, to perform some of the tasks of the Russian army. The second war was characterised by the clampdown on TV stations in Russia, the torture and murder of radio and newspaper journalists, and the lack of a cogent anti-war movement in Russia. In addition, under Putin, the mode of government has changed from an oligarchic capitalism to an authoritarian one, xenophobia is rife within Russia, and the West is still either indifferent or complicit with the war in Chechnya. Many very interesting points are brought together in chapter five.

Chapter six pauses to discuss the role of Islam in the Chechen struggle, from the advent of Islam in the North Caucasus in the eighteenth century to the present day. Especially since September 2001, it has been the Russian claim that while America is battling a world-wide trend of Islamist terrorism, Russia is battling the Chechen branch of the same problem in the North Caucasus. Here Wood’s method is to show how at every step, since the eighth century the main motive for the struggle of the Chechen people has been the aspiration to freedom and the establishment of an independent state; Islam has always been second to these aspirations or used to further the cause of the first. Here one wonders whether this is really true or whether it is Wood’s way of refuting the Russian claim, which is undoubtedly false, as the Chechen struggle pre-dates 9/11 by 400 years. With regard to the role of Islam in the North Caucasian struggle, one would do well to examine Wood’s stance by looking to other sources.

In chapter seven, Wood brings to the attention of the reader the “regionalisation” of the Chechen conflict, illustrating how many North Caucasian peoples are now rebelling against Russian rule, albeit for a variety of reasons. For instance, in the Beslan tragedy of September 2004, of the fifty or more captors, only 5 or 6 were Chechen; most were Ingush. Similar trends are permeating Dagestani society and other parts of the North Caucasus. In this chapter, Wood reasons, to defuse this “regionalisation” of the conflict will require “the establishment of a stable and just peace in Chechnya”.

The last chapter brings the reader up to date with the present ills of Chechen society. Today we see the continuing damage of ‘Chechenisation’ on the Chechen people. Although Putin has declared the end of the war and the ‘normalisation’ of Chechen society by placing a pro-Moscow puppet, Ramzan Kadyrov, as president of Chechnya, along with a private army of a few thousand militia, the kadyrovtsy, which perpetrate atrocities upon the Chechen people, heretofore committed by the Russian army on Russian’s behalf, Russia continues to receive body-bags in the tens every month. Time and again Wood makes the valid point that no poll or referendum held by an occupying power will yield a democratic result on the true aspirations of the Chechens. Chechnya and its people are in a desperate situation, but Wood concludes his book by repeating that “there can be no peace until it is once again possible for the Chechens freely and democratically to determine their own future”.

Wood’s book is a welcome contribution to the literature on Chechnya: well-researched and gripping to the last. Specifically, he argues the case of Chechen independence well and refutes contemporary arguments against it, leaving the reader in no doubt that the issue of Chechen independence should be at the forefront of any debate on the crisis.