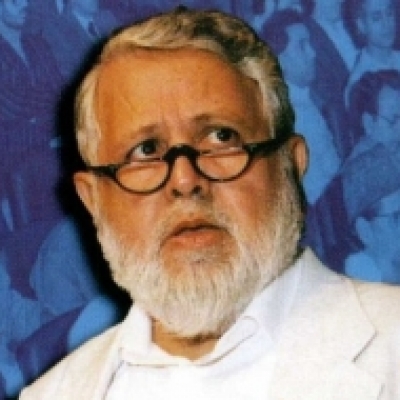

Kalim Siddiqui

Kalim Siddiqui[Paper was written and published as the introduction to Kalim Siddiqui (ed), Issues in the Islamic Movement 1981-82, London and Toronto: The Open Press, 1983, and reprinted in Zafar Bangash (ed), In Pursuit of the Power of Islam: Major Writings of Kalim Siddiqui, 1996.]

Dimensions are an aid to description. But no description of a reality as complex and multi-dimensional as the Islamic movement can ever be complete. Any description will always be a partial description. Nonetheless, a description there must be. No analysis can begin without description. Initial observation reveals not only the immediately observable facts, but also the need for further observation over a period of time to discover patterns in the repetition of behaviour.

All writing is based on observation and partial description. This is especially true of journalism. When the Crescent International came out as the 'newsmagazine of the Islamic movement', its editors and writers assumed that an Islamic movement existed. More accurately, perhaps, they simply hypothesized that there was in existence a global Islamic movement1 which the journal would observe, reflect and describe. After reading the Crescent International for two years, it is now possible to see the outline of the Islamic movement emerging through the mist and fog of contemporary history and current events.

It can be said that the Crescent International has 'covered' the Islamic movement only in outline. Or it may be said that for the most part the Crescent International has been busy describing the environment of the Islamic movement rather than the Islamic movement itself. The truth is probably that the paper has covered the interactions between the Islamic movement and its environment. Thus, when it has tried to dig deep into any part of the Islamic movement, what has it found? It has found that the environment of the system (the 'system', of course, is the Islamic movement) has penetrated the system. Large parts of the system (and this applies also the entire Ummah) are now controlled by its environment.

What, then, is this environment? The environment of a religion is all other religions; the environment of a movement is all other movements; the environment of a civilization is all other civilizations... and so on. It is immediately clear that Islam is at once all three: religion, movement and civilization. When viewed in this context it is also clear that the history of Islam, in at least one of its dimensions, is a record of the Muslim Ummah's interactions with its non-Muslim and often, or nearly always, hostile environment. The jahiliyyah (primitive savagery and ignorance) of Makkah was the immediate environment of Islam. The da'wah of Islam reclaims man from his jahiliyyah environment and makes him secure in a series of institutions, the highest and best of these being the Islamic State. The Islamic State represents the geographical area of the world that has been reclaimed from jahiliyyah and consolidated in Islam. Experience tells us that the environment does not retreat and go away. It leaves behind its traces, tries to creep back in and, in its own turn, reclaims Muslims and the areas of Islam for jahiliyyah. In Islam if any Muslim returns to a state of jahiliyyah, his punishment is very severe. Such is the deterrence with which Islam defends the human factor that is one part of itself. The persistence with which non-Islam tries to prevent Islam from spreading is all too familiar to Muslims. Islam has rarely lost men in any great number in this way, with the possible exception of Spain.

The interaction of Islam as a movement, consolidated in a State, with other movements and un-Islamic States in its environment is another level of interaction. In the history of Islam this level of interaction began after the hijrah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace, to Madinah. In time, this interaction turned into a contest between two civilizations, the civilization of Islam and the western civilization. At the present time we are almost exclusively concerned with the interaction of Islam as a civilization with its environment, the western civilization. It is this interaction that is the daily fare of the journalist, the writer, the observer, the recorder, the historian, the philosopher, the activist and, to borrow a phrase coined by Hamid Algar, the 'concerned Muslim'.2 Unless we understand the true nature of this interaction, a struggle for supremacy between the two civilizations, we will understand little, if anything, of the contemporary scene.

An environmental dimension is essential for an analytical model of the Islamic movement.3 In other disciplines, such as biology or international relations, it is relatively easy to delineate the environment. In biology everything that exists outside the living organism is that organism's environment.

In international relations everything outside the physical boundaries of a State is that State's environment. Concern with the environment is a basic human instinct. A man needs to control at least some part of his environment to survive. He achieves this by enclosing space and calling it his 'house', and by having others to live with him and calling them his family, clan, tribe or nation. He acquires modes of transport to reduce the distance between various parts of his environment. He needs modes of exchange, such as money, to acquire control over or access to goods and services controlled or produced by other men. He needs exercise to stay healthy but, should 'germs' present in the environment enter his body, he needs medicine or surgery to get them out of his 'system'. The smallest particle in the air that gets in a human eye is very painful, as painful as a needle, a bullet or a knife would be in other parts of the same body. Some parts of the 'system' are more sensitive to the environment.

Allah subhanahu wa ta'ala has created man physically weak in relation to most of his environment. He has also endowed man with faculties of mind and body that enable him to acquire control over all parts of his physical environment. But, in His wisdom, He has not endowed man with the ability to discover for himself how best to arrange his relationships with other men and groups of men, from family to nation. A non-Muslim knows instinctively that he should procreate. He establishes temporary, permanent or semi-permanent relationships with the opposite sex. He sets up house and family. He secures for spouse and children security in wider arrangements of clan, tribe, racial group, peer group, class, and ultimately nation and coalition of nations. He internalizes his experience into theories and combines these theories into 'knowledge', now called 'science'. This is also otherwise known as the 'scientific method.' We know it as the secular development of man. The western civilization today is the epitome of man's secular development, though of course parts of it have gone through the Christian and Jewish religious experiences. Recent additions to the western civilization have 'enriched' it with such religious experiences as those of Hinduism and Buddhism. But, fundamentally, the west (which is no longer a geographical term, but a term used for a global 'civilization') has reduced all religious experience to the level of secular experience. Religion was merely a 'stage' in the secular development of man. According to the west, man is himself the repository of all wisdom. All the knowledge that man needs he either already has or is well on his way to acquiring. Man has no Creator, he is self-contained and sovereign unto himself. He owes nothing to anyone outside himself, he is not responsible for his behaviour to anyone or anything except his own 'interests', which he alone is capable of articulating and defending. Man's own good, as determined by himself is the highest interest and responsibility of man. Man has no peer other than himself and certainly no superior. He applies the same method, the empirical method, to all his needs of observation, explanation and prediction. He expects everyone, all men, to agree with him, otherwise they are 'backward' or worse. Such is the behaviour, such is the theory, such is the philosophy, such is the wisdom, and such indeed is the arrogance of man in the western civilization. What the western man does not know, or does not want to know, is that this secularism has become his religion; he is more fanatical with his secularism than any religious fanatic. On top of that, the secular man's behaviour is also free of any moral inhibitions, because his religion is free of notions of morality. The only morals known to the religion of science and secularism are those of convenience and short-term expedience. He is, in short, a human beast, and the modern world is a living testimony of beastly human behaviour at all levels.

Thus the whole of the religion of secularism is the environment of Islam and the Islamic movement. And because of the nature of secularism, the environment that confronts Islam is an intensely hostile one. It is probably true to say that Islam has always had to contend with a hostile environment. This, however, mattered little so long as Islam remained dominant within itself. This is a point of some significance, and needs elaboration.

In the Sunnah and the Seerah of Prophet Muhammad, upon whom he peace, there was a constant struggle between Islam and non-Islam. The struggle lasted 23 years, and the Revolution of the Qur'an was interwoven in the course and processes of this long and hard struggle. It was only after Islam had become dominant over its immediate environment that, in the words of the Qur'an, Islam was 'completed'.4 The very last verses of the Qur'an that were revealed are those of Surah al-Nasr. They speak of victory that is only with the help of Allah, and the faithful are reminded of this fact. They are firmly told that victory is no occasion for self-praise and rejoicing; instead, says the Qur'an, in victory, which is with the help of Allah, the faithful should celebrate the praises of Allah and should beseech Him for forgiveness for their sins.5

The victory of Islam was and must always be over its hostile environment. Within a few years of the Prophet's death, the Islamic State he founded had extended its dominance to the shores of the Atlantic and the Pacific, and in the process the Muslims had also smashed the two superpowers of the time, the Byzantine and the Sassanid empires. From then until at least the eighteenth century Islam and the Islamic civilization remained the dominant civilization in the affairs of man. The west did not really succeed in finally dismantling the last political manifestation of the dominance of Islam until the defeat of the Uthmaniyyah State in the First World War and the abolition of the khilafah in 1924. Despite the tragedy of Spain (1610), according to A. J. P. Taylor, the celebrated English historian, the European civilization did not really get going until the twentieth century.6 In other words, the civilization of Islam did not finally lose its dominance within itself and in relation to the competing environmental civilization until the early part of this century.

It is a particular characteristic of a hostile environment that it does not stop at the frontiers of the system it overcomes; a hostile environment goes on and penetrates the system. The hostile environment tries to absorb the system it overcomes into itself. If for some reason it cannot absorb it, or realizes that it cannot absorb it, the dominant environment tries to convert the defeated system into a permanently subservient sub-system of itself. If one looks at the colonial period and the post-colonial experience of the traditionally Islamic societies, the point becomes clear. The western civilization has taken care to destroy all the traditional pillars of strength of Islamic civilization.

The political, military, social, economic, cultural and educational structures and institutions that were the supports of the civilization of Islam have either been destroyed entirely or removed from the mainstream of life. In their place institutions developed in the west have been planted. It is not an accident that Muslims who are the most westernized are dominant in Muslim societies today. All institutions in Muslim societies are run by westernized Muslims. To put the point in its simplest form, the hostile environment has succeeded in creating its agents within the Islamic societies.

The question we need to consider is how is it that the hostile environment has found its advocates and exponents among Muslims? It is necessary that we answer this question adequately because the response of the Islamic movement to the challenge of enemy penetration of Islam depends upon it.

What has to be noted at the very beginning is that internal weakness in the system itself provides opportunities for its eventual penetration by its environment. It can be argued, indeed it has been argued, that the system, the civilization of Islam, began to weaken at its centre even when it was rapidly expanding at its frontiers.7 Be that as it may, the fact is also that the civilization of Islam went on to remain dominant within itself and to acquire and retain dominance over its larger environment for so long that deviance and weakness at the centre became institutionalized. Biological systems, such as the human body, often live and play dominant roles for many years after suffering partial disabilities or after undergoing major surgery on vital organs. Other social systems, such as the family, often survive major upheavals to continue to perform their basic functions. States and other political systems of all varieties have suffered military defeats and other setbacks and recovered to their former roles, sometimes reaching new heights of attainment. The core of Islam, however, had been given shape by none other than the Prophet of Islam himself, upon whom be peace. The power of Islam is more than the sum total of the power of its political and military arms. The power of Islam is most effective when consolidated in the Islamic State. But the defeat, penetration or even abolition of the Islamic State does not leave Islam and Muslims without power. In such an eventuality the power of Islam becomes diffuse awaiting its reconsolidation in the Islamic movement and eventually in the Islamic State.

Nonetheless, the fact of defeat and domination by an alien civilization was a new experience for Muslims. This was a situation they had not expected and were not prepared to face. Inevitably this new experience of weakness and domination by the environment caused a great deal of bewilderment in all parts of the Ummah. But the Muslim ruling classes, the landed aristocracies, and those whose livelihood was directly dependent upon the service of the State or political and military patronage, were most adversely affected. Their immediate reaction to defeat was to rationalize it, to reconcile with it, and to seek the service and patronage of the new rulers. The former rulers of Muslim States had ruled in their own interests; now their courtiers accepted foreign rule, also in their own interests. It is from this class of Muslim courtiers and sycophants that the new 'leadership' emerged; a leadership which persuaded Muslims to accept and internalize the culture and civilization of the new European rulers. It is this class that has thrown up men of the fame, calibre and notoriety of Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, Mustafa Kamal, Reza Khan Pahlavi, Abd al-Aziz Ibn Saud, Gamal Abd al-Nasser, Abol Hasan Bani-Sadr and countless others. It is this class that has become ruler in its own right in the post-colonial nation-States. These rulers are today the instruments of the penetration that Islam's hostile environment has achieved and retains in the body of Islam. These rulers rule with political, economic and social structures created in the image of the colonial powers' structures, and they are still dependent for their survival on the environmental support systems provided by the dominant western civilization.

In its environmental dimension, therefore, the Islamic movement is bounded by a hostile civilization which has also acquired a foothold in the house of Islam itself. The power of this foothold of the alien civilization in the traditional areas of Islam has been clearly demonstrated in Iran. The ferocity of the late shah's regime against the Islamic movement was understandable and expected. But after the Islamic Revolution the westernized crust of the old order has stayed behind, and continues to fight a vigorous rearguard action to prevent the consolidation of the Islamic State. This counter-revolutionary campaign has been supported, supplied and orchestrated by the western civilization beyond the frontiers of Iran. There is no neat geographical line separating the Islamic movement and its environment. The interaction between the Islamic movement and the environment is also the struggle for supremacy within the house of Islam. This struggle is between the Islamic movement and the Muslim followers of the religion of secularism. In this sense the Islamic movement is unique; its hostile environment includes all the regimes and the ruling classes of modern nation-States in the Muslim world. The greatest success of the western civilization in its dealings with Islam is not scientific or technological; it is simply that there are now Muslims and Muslim governments lined up against Islam.

A discussion of the political dimension of the Islamic movement must begin with politics itself. The word 'politics' as such is unknown in the original sources of Islam. Islam is guidance to mankind in all departments of life. As far as Islam is concerned, life is a single seamless garment. The life of the Prophet, upon whom be peace, was spent as much in meditation in the caves around Makkah, or in meditation and prayer in his private quarters in Madinah, as on the battlefields and in consultation with his advisers on matters of State. When the Qur'an speaks of having 'completed' Islam, it obviously means what it says: Islam is a complete all-inclusive system. The Quraish of Makkah, when they opposed Islam, did not stop to ask whether Islam was 'political'. To them the basic message of Islam that 'there is no god, but Allah' was 'political' enough; it challenged the existing structure of authority in Makkah and wanted to replace it. That message of Islam is timeless and universal. So long as there exist 'political' or other human organizations that do not recognize the supremacy of Allah and are unjust and oppressive, it is the duty of the Islamic movement to bring them to justice and to end oppression. This is a duty imposed upon the Muslims by the Creator Himself. In this matter the Muslim has no choice. A Muslim who is inactive in this field is in active rebellion against Allah. Any attempt to deny this role of Islam is an attempt to deny the authority of Allah over all His Creation. Of course Islam allows people not to accept Islam if they so wish.8 At the same time Allah warns that unbelievers will combine to create 'tumult and oppression on earth and great mischief.'9

There is no need for us to define 'politics', nor is there any need to enter into a futile debate over the 'role of religion in politics.' These are the concerns of the detractors of Islam and of the regimes in the Muslim world today that have everything to fear from the Islamic movement. For the Muslims it is sufficient to know that the revolution of the Qur'an was interwoven in the struggle of the Prophet and his companions. That struggleCthe 'movement'Cwas also the living manifestation of the message. The struggle as Sunnah is indeed an integral part of the message. The outcome of that struggle was the Islamic State.

The Islamic State is an inseparable part of the totality of Islam. It may be significant to note that Allah subhanahu wa ta'ala did not declare the completion of Islam until after the Islamic State had been firmly established and made dominant over its immediate environment. The Islamic State is the Muslims' natural habitat and their dependence on the Islamic State is as complete as that of fish on water. If Muslims survive without the Islamic State they survive like fish in a bowl of water or in an aquarium. The nation-States where Muslims live today are aquarium-like enclosures where the Muslims are in fact denied their freedom. The Islamic State is the only instrument of freedom as well as its guarantor. The only freedom that has any meaning to a Muslim is the freedom to live and die for Islam in an Islamic State. Any attempt to produce a model of Islamic practices which allows Muslims to opt out of the struggle is an attempt to impede the message of the Qur'an and the Sunnah. A State that is dependent for survival on the traditional enemies of Islam cannot be an Islamic State. And no State which relies upon any form of nationalism for its legitimacy can at the same time claim to be Islamic. In this sense the political dimension of the Islamic movement is all-inclusive. However, there are two areas that need close attention. The first is the area of political ideas, norms and behaviour that Muslims have acquired from their contact with the west and have mistakenly come to regard as 'Islamic'; the second is the political culture of the Muslims as it has taken shape over time.

In the first category, the greatest confusion arises from the failure to distinguish between a nation-State and an Islamic State. If there were such a subject as political biology, it would be possible to show that the genes of the two are not only different but mutually exclusive and incompatible. Perhaps one should assert that while the nation-State is a 'political' State, the Islamic State is a muttaqi State. The Islamic State is also the chief instrument of Divine purpose on earth. There cannot be two concepts more opposed to each other than 'politics' and taqwa in the modern world. A modern politician cannot be muttaqi and remain a politician. Those who have tried have found themselves in all kinds of difficulties. Perhaps all the 'political' behaviour of Muslim political parties, calling themselves 'Islamic' for good measure, has been of this variety for a hundred years or more. Their political wisdom has so clouded their understanding of Islam that a leader of the Jama'at-e Islami, Pakistan, has argued before the Lahore High Court that the modern methods of elections on the basis of competing political parties are 'exactly according to the democratic values of Islam'. This 'Islamic politician', who was also a Minister in the Martial Law Cabinet of Zia ul-Haq, went on to argue that 'political groups' and 'political parties' had existed during the khilafah al-rashidah itself.10 Such are the pressures of modern politics on the practitioners of the art that the Muslim politician has to distort the original sources of Islam to serve his purposes and those of his party. One particular faction of the Ikhwan al-Muslimoon participated in a press conference in New York on April 2, 1982. The platform was shared between Monzer Kahf, a well-known Ikhwan figure who was described as a representative of the Islamic Front in Syria, and Hammoud El-Choufy, who described himself as a Ba'athist but explained that he belonged to a different faction of the Ba'ath Party than the Syrian President, Hafiz al-Asad. El-Choufy had been Syria's permanent representative at the UN until his 'defection'. The press conference launched The Charter of the National Alliance for the Liberation of Syria. The Alliance, said a press release, was launched 'somewhere in Syria' on March 11, 1982, after 'responsible dialogue and determined discussions between the two political trends of the Syrian people—Islamic and Arabic.' The members of the Alliance are the Muslim Brotherhood (the Ikhwan), the Ba'ath Arab Socialist Party, the Islamic Front in Syria, the Arab Socialist Party, the Nasserites, and 'independent political dignitaries and individuals in Syria.'11

Kahf belongs to the same faction which has carried out a world-wide propaganda campaign against the Islamic government of Iran for its alleged 'links' with Asad. He and his faction's open alliance with Ba'athism and socialism are supposedly somehow sanctioned by Islam, for their Charter ends with a suitable quotation from the Qur'an. A close reading of the Charter shows that in it Islam comes a poor second to Arab-Syrian nationalism.

The behaviour of 'Islamic' political parties and their leaders throughout the colonial and post-colonial period is witness to this type of schizophrenic behaviour. Some elitist anti-colonial nationalist parties, such as the Muslim League in British India, used Islamic slogans for the limited purpose of popular mobilization and political communication. The Muslim League was careful never to call itself 'Islamic.' But the secular political behaviour of 'Islamic' parties has prevented them from challenging the very foundations of the post-colonial order and the credentials and fabric of the nation-State system. In fact such 'Islamic' parties themselves had to acquire nationalist credentials before they could operate in the nation-States. The primary examples of this are once again the Jama'at-e Islami and some factions of the Ikhwan.12 This failure to confront the nation-State structure as fundamentally wrong and a continuation of colonialism by other means has not only compromised the 'Islamic' parties themselves. Its more damaging impact has been in the opposite direction: it has allowed the nation-States to call themselves 'Islamic'. Hence the whole plethora of 'Islamic' institutions with which these colonial States have equipped themselves. Because their leaders and 'fathers of the nation' had Muslim names and used Islam for deceiving their people, the nation-States and the political systems they created with the help of imperialism have also claimed to be 'Islamic'.

The effects and consequence of this successful deception can be seen clearly over a wide range of contemporary behaviour in both domestic and international politics. Perhaps nowhere has this deception been taken further than in Malaysia. There, because of the precarious balance of population between Malays and Chinese, the Malays, all Muslims, have foisted Islam on the Chinese as the 'official religion of the State'. Islam has been marshalled in the service of what is essentially a secular racialist system. In Malaysia, an artificial creation of the British, 'democracy' has been so designed as to ensure Malay dominance. State patronage, especially in education, is 'Islamic' and therefore exclusively for the Malays. Similar practices are also common in 'Islamic' Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States, where work is done largely by migrant labour and the local Muslims have become a rentier class. All these Arab 'Islamic' states are spending enormous sums of money on trying to convert their Muslim populations into 'nations'. They have introduced 'national anthems', 'national days', 'national' football teams, 'national stadiums' and much else beside. Housing, health and other welfare services are for the exclusive use of the 'nationals'. Nationals also get preferential rates of pay for similar jobs and a form of 'job reservation' system, akin to apartheid, has come into existence. Migrant workers are controlled by a vicious system of indentured labour. This has led to perhaps the worst form of slavery that the world has ever known. The political systems that require this degree of repression for their own survival not only go unchallenged by the 'Islamic' parties but also manage to claim to be 'Islamic' themselves. The whole of the feudal-capitalist order is passed off as essentially 'Islamic', needing only minor adjustments in such areas as riba.

Only in Iran has the Islamic movement set itself on a course of total rejection of the existing order, with spectacular results. It is still not clear, however, whether this rejection was originally intended to be of the entire nation-State structure or only of the Pahlavi State. It seems that the rejection of the entire nation-State system was clear in the minds of such men as Ayatullah Muhammad Husain Beheshti and Ayatullah Mutahhari, but a strong faction that wanted to settle for far less than a total Islamic Revolution was also in the vanguard. This faction held sway in Iran for some time after the Revolution. The most outstanding representative of this group was undoubtedly Abol Hasan Bani-Sadr, who actually managed to become President. Imam Khomeini appears to have deliberately allowed this faction time to come to terms with the Revolution or get out. Sadiq Qutbzadeh, the former Foreign Minister, was the last of this group to get involved in a plot to kill the Imam. It is early to say whether the 'liberal soft centre' in the Revolution has now totally dissolved.13 What is certain is that the old Pahlavi nation-State is now dead, though the Constitution, written in 1979, continues to retain some 'nationalist' and sectarian provisions that it could well do without.

In the political process in all other parts of the world, the 'Islamic' parties have done badly. There have been few elections, but enough to establish the mediocrity of the 'Islamic' politicians. Nowhere has an election produced a majority for an 'Islamic' party. The reasons for the poor performance of 'Islamic' parties are an essential part of the political dimension of the Islamic movement. Perhaps the most telling point that has to be made is that none of these 'Islamic' parties has emerged from among the ulama or has had the active support of the ulama. The 'Islamic' parties emerged too close to the political root of the nationalist parties. Like the nationalist movements, the 'Islamic' parties became involved in the immediate 'political' concerns associated with securing 'independence'. What no one realized at that stage was that the colonialists were merely preparing for the 'transfer of power' to a westernized elite of their own creation and that 'independence' was only another name for continued dependence and neo-colonialism by more subtle means. In British India the only man to see through the nationalist game of the Muslim League was Abul Ala Maudoodi, who had founded the Jama'at-e Islami in 1941. 'It is difficult to imagine', wrote Maudoodi, 'how a nationalist State based on western democracy can be instrumental for Islamic State'. According to him, such a State would be no different from the secular State of the type demanded by the Hindu-dominated Indian National Congress and implicitly accepted by the British. Maudoodi was, of course, entirely right. He also called for an 'Islamic movement' as a prerequisite for the creation of an Islamic State. Maudoodi's Islamic movement, however, was barely off the ground when the Muslim League secured the 'God-given State of Pakistan' and the British transferred power to the 'dominions' of India and Pakistan. Maudoodi decided to move to Pakistan. There he was accused of having opposed Pakistan. Maudoodi, instead of standing his ground and creating an Islamic movement to convert nationalist secular Pakistan into an Islamic State, allowed the opposite to happen; the Jama'at-e Islami itself became a national party instead of an Islamic movement. It is significant to note that Maudoodi was not an alim, and the ulama, despite his great self-acquired erudition, did not accept him as one of them. Equally, Maudoodi did not fit the westernized elite's nationalist mould.

At this point a new factor pushed Maudoodi and the Jama'at in the secular direction. This was the emergence of a large number of lower middle class young men who were educated in the western tradition but had been more than a little touched by the Islamic rhetoric of the secular Muslim League and the Pakistan movement. This was a largely urban group, and its number was greatly swelled by a similar social group that came to Pakistan from India. These refugees were naturally a little more 'Islamic' in their immediate preferences. This urban group in Pakistan soon realized that the Muslim League's commitment to Islam had been fraudulent, and its members flocked to the Jama'at-e Islami. Yet their hero had been Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and their personal lifestyles and careerist orientations were identical to those of the entirely secular 'right' and 'left' in Pakistani society. Young men from this urban group flocked to the Jama'at's student wing, the Islami Jam'iat-e Talaba, in Pakistani universities. Maudoodi failed to realize the danger that this exclusively urban following spelt for his Islamic party. He welcomed them and eventually became their prisoner. He failed to launch an attack on the biases, attitudes and thinly disguised secular ambitions of this group, all in the good name of Islam. Instead of preparing and training them for the Islamic Revolution that he had so passionately written about in the days before Pakistan, Maudoodi now told these students that they were the 'leaders of tomorrow'. This is precisely what they wanted to hear. The Jama'at leadership that took the party into a Martial Law Cabinet under General Zia ul-Haq in August 1978 had all joined the Jama'at from this urban group in the party's early days in Pakistan.

Had Maudoodi been leading a revolutionary Islamic movement of his own initial conception, this urban middle and lower middle class 'liberal soft centre' would have hardened, or been left out or expelled. This is precisely what happened in Iran. There the revolutionary movement carried an urban 'soft centre' into the post-revolutionary phase. But the Islamic Revolution proved too powerful for them to manage and control. A brave effort was made by Bani-Sadr and some others, but ultimately they had to get out. The Revolution in Iran also produced a generation of revolutionary youth that was prepared to die for the new Islamic State. This revolution-hardened generation has secured the Islamic Revolution from within and from without against external intervention and invasion. In Pakistan, by contrast, the 'political' methods of the Jama'at have produced a generation of personally ambitious 'Islamicists' who desire painless 'Islamization' that demands few, if any, sacrifices.

In Egypt, Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimoon had a much clearer vision, and jihad was always part of the movement's framework. Nonetheless, Imam Hasan al-Banna fell into the same nationalist trap. The Wafd accused him of 'obstructing the national movement' against the British. In the last two years of his life (he was assassinated by the king's agents on February 12, 1949) Banna's actions were almost exclusively determined by the need to answer the charge of being 'anti-national'.14 The Ikhwan, too, had attracted the westernized 'soft centre' of urban middle class followers. The suppression of the revolutionary Ikhwan leadership by successive regimes in Egypt has left this 'soft centre' to peddle its 'Islamicity' in the corrupt world of the Saudi princes and Gulf shaikhs. The area offered rich pickings and these Ikhwan expatriates fell for them.

They have also given rise to a second generation of 'Islamicists', who live mainly in Europe and North America. These 'servants of Islam' convinced themselves and their patrons that Europe and America were ready for Islam. Almost nothing could have suited the corrupt Arab regimes better. They wanted to get rid of Islam anyway; where better to send it than to Europe and America? The new 'Islamicists' received millions upon millions of dollars to create 'Islamic councils' and other institutions in Europe, America, Africa and lately in Australasia. Official largesse was backed by private donations. Saudi Arabia created such front organizations as the Dar al-Ifta, the Rabitah al-Alam al-Islami and the World Assembly of Muslim Youth to funnel funds to plant 'Islamicists' throughout the world. In Europe and America, the Ikhwan 'soft centre' has been joined by its counterparts from the Jama'at-e Islami in Pakistan and India. Many of the Jama'at leaders have taken well-paid posts in Saudi Arabia itself. That country, under perhaps the most corrupt rulers that any Muslim country has had in all history, has also become a haven for 'Islamizing' professors, itinerant maulanas and other professionals of this kind.

All this and much besides is part of the political dimension with which the Islamic movement is saddled today. Much that goes under the banner of the Islamic movement does not properly belong to it. This is another example of the extent to which the political environment of the Islamic movement has penetrated the Islamic movement.

The need to introduce the concept of political culture is entirely analytical. An attempt is being made to develop, piecemeal, an analytical model of the Islamic movement as an aid to description, explanation and, eventually, prediction of behaviour. As has already been noted, much of the 'political' behaviour of even the 'Islamic' parties takes place in the secular nationalist frame-work introduced by the western civilization. One does not need to refer to the political culture of Islam to describe and explain the behaviour of the modern political actors—the nation-States, their institutions, and political parties. There is, however, another question that needs an answer: how do the traditionally Muslim societies react to modern political behaviour? The answer to this question depends upon our ability to understand the true nature of a traditionally Muslim society. The overwhelming evidence would appear to suggest that Muslim societies have, by and large, not responded positively to modern political behaviour. The Muslim masses seem to resist modern political institutions, their style and content, and their leadership. As evidence, let us note that nowhere in the post-colonial Muslim world has the political system acquired a broad 'popular' base. In every post-colonial Muslim situation the political systems have become more and more authoritarian and dictatorial. In all these countries the Muslim masses have, if anything, moved in the direction opposite to the one desired by their governments and dominant political parties. In most countries, effective control and power have passed to a narrow-based elite, largely western in orientation and militarist in preferences. All the Muslim ruling classes that have emerged under the patronage of the colonial powers have one thing in common—their partial or total contempt for Islam and for the Muslim masses. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the Muslim masses, too, have nothing but contempt for their post-colonial rulers, whose conduct is often worse than the conduct of the European colonialists had been.

All this is fairly obvious. Everyday observation also confirms that the Muslim masses do not accept the post-colonial political systems as belonging to them or to their Islamic heritage. These political systems remain rootless, isolated impositions on traditionally Muslim societies. What is more surprising is that even the 'Islamic' political parties such as the Jama'at-e Islami and Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimoon failed to strike roots in the Muslim political culture. Both these movements have remained almost as isolated and rootless as their more secular contemporaries. In Pakistan, the Jama'at leadership has tried to explain this popular rejection of the Jama'at as the rejection of Islam by the people. The Jama'at has explained its own isolation in terms of the people's inability to understand Islam. According to the Jama'at, the people of the subcontinent are only 'nominal Muslims', and do not want Islam. The Jama'at leadership has also tried to take credit by claiming that at least the urban 'educated classes' have supported the Jama'at.15

There is some evidence that secular parties, such as the Muslim League, succeeded in securing short-term popular support for their political programmes. The Wafd in Egypt also secured a measure of support for the 'national question'—the evacuation of British troops from the Canal Zone. In both these instances the anti-imperialist sentiment was very strong. In the case of the Muslim League in India, the Muslim masses remained cool towards it from its foundation in 1906 to its adoption of the Pakistan demand in 1940. Before 1937, the Muslim League polled fewer than 5 per cent of Muslim votes on the basis of separate electorates for Muslims. It was only when the Muslim League raised the Pakistan slogan, laced with Islamic symbolism, that the Muslim masses warmed to it. But it was no part of the Muslim League's purpose actually to mobilize the Muslim masses in the service of Islam. All they wanted was a secular nation-State called Pakistan where they, the Muslim lawyers, merchants, nobles and landlords would be the permanent rulers. They got such a State in 1947 and have kept it free of Islam or popular participation ever since.16 The nationalist parties managed to secure a measure of popular participation when they mixed it with Islam and an external enemy. In British India the fear of the Hindus was a powerful catalyst, in Egypt the hatred of the British, in Mussadeq's Iran the desire to nationalize the oil company, in Indonesia the hatred of the Dutch, in Algeria the hatred of the French, and so on. All these periods of popular participation lasted only until the nationalist leadership had itself secured control over the State. Once in control, the nationalist leaders behaved no differently from the colonialists they replaced. Not surprisingly, and for quite obvious reasons, the brief periods of mass participation in national political movements did not lead to the emergence of participatory institutions of government.

In view of this evidence a reasonable assumption would be that the Muslims have a political culture which is resistant to the secular nationalist 'political processes' of the post-colonial period. This political culture has not responded even to the 'Islamic' political parties operating in the secular framework. This political culture of the Muslim masses is clearly opposed to the imported political culture of the secular post-colonial regimes and the westernized political elites of the nation-States. In Muslim societies today there exist two competing and mutually exclusive political cultures: the imported political culture of the ruling classes and the indigenous political culture of the Muslim masses.

This is an important dimension for the Islamic movement. The Islamic movement must now ensure that it does not become part of the western political culture of the post-colonial order. Instead, the Islamic movement must ensure that it belongs to and remains firmly rooted in the political culture of the Muslim masses. If this political culture of Islam has itself become contaminated by values and norms alien to Islam, then the Islamic movement must eradicate such influences. Whatever the situation, there can never be any reason or justification for participation in the imposed and oppressive political culture of the west which at present provides the rulers with their political theory and framework of government. The Islamic movement must declare war on the influences of the political culture of the west in Muslim societies.

The question that remains to be answered is, what precisely is the Islamic political culture? This question requires a more detailed treatment than is possible in these pages. Here only a brief attempt can be made to indicate in outline the major factors that go to make up the political culture of Islam. It is perhaps useful to divide the roots of the political culture of Islam into primary and secondary roots. The primary roots are clearly the Qur'an and the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace. The Seerah (life) of the Prophet and the struggle between Islam and the forces of jahiliyyah that occurred during the life of the Prophet are clearly part of the primary roots of the political culture of Islam. The 40 years of the rule by the first four khulafa, the khulafa al-rashidoon, which ended with the death of Ali ibn Abi Talib in 661AD, were clearly a direct continuation of the State established by the Prophet himself and as such part of the primary roots. The Shi'a regard the authority of the twelve Imams as a direct continuation of the authority of the Prophet. The imamah extends the period of primary roots to 329AH, when the Twelfth Imam went into gha'ibah (occultation). This is of considerable advantage not only because of the great piety and learning of the Imams, but also because of their firm stand against the early emergence of tyranny in Islamic history. The Imams are all equally respected by the Sunnis and Shi'is. The Sunni and Shi'i schools of thought do not have to accept each other's theological positions on issues of khilafah and imamah to benefit from the combined doctrines and the undoubtedly rich common historical experiences.

Imam Khomeini, who is, of course, personally committed to the Shi'i school of thought, has made a great contribution towards the emergence of a combined political thought. Talking of the many devices that the enemies of Islam at present use to divide the Ummah, he has said, 'more saddening and dangerous than nationalism is the creation of dissension between Sunnis and Shi'as alike, and it is as a result of this ignorance that clashes and enmity have arisen. Certainly these divisions did not exist in the earliest age of Islam.'17 In the same interview Imam Khomeini refers to the position of some Sunnis who regard rebellion against oppressive government as incompatible with Islam. This position of some Sunnis, said Imam Khomeini, is based upon an incorrect interpretation of the verse of the Qur'an concerning obedience. Algar has penned a note to this statement of Imam Khomeini. First he quotes the verse in full:

'O you who believe, obey God, and obey the Messenger and the holders of authority from among you.'18

Algar adds:

...it is true that a number of classical Sunni authorities including Mawardi (d.450/1058), Ghazali (d.505/1111), and Ibn Taymiya (d.728/1328), attempted to legitimize both the hereditary khilafah and the usurpation of power by military dynasties, by means of their political theories. Their theories were in large part, however, an attempt to palliate the evil effects of a situation they saw no hope of changing. What is indisputable is that the influence of those theories has far outlived the circumstances that produced them and it continues to affect the political attitudes of Sunni Muslims, although it is now diminishing.19

This brief discussion shows that the primary roots of the political culture of Islam are healthy and that the entire Muslim Ummah, Shi'a and Sunni, can draw from this common root without difficulty. These primary roots have the strength and the vitality required to reunify the Ummah in a single Islamic movement.20 The secondary roots have become tangled in the course of history. These can be straightened out in the framework of a dynamic Islamic movement and in the context of its struggle against the neo-jahiliyyah that prevails today.

The basic resource of the Islamic movement is its size. Christianity can probably count more heads than Islam. But these figures will not be comparable for the simple reason that there is no Christian civilization in existence or trying to recover its lost ground. All Christians, lay and clergy, now accept the western civilization's interpretation of religion as a 'stage' in human development which has passed and has little further relevance beyond the personal spirituality of a few individuals. There is nothing comparable to the Islamic movement in Christianity. There is no one trying to establish a 'Christian State' or even a 'Christian civilization'. No religion, philosophy or ideology today, except Islam, challenges the right of the secular world to exist. Islam in this sense is unique. It insists that human behaviour directed and guided by Revelation and Prophethood alone can lead men to true development, progress and happiness, and that all secular behaviour at all levels is jahiliyyah and rebellion against the Creator. This position of Islam is held by one thousand million living Muslims. Or perhaps not quite that number because a handful, but only a handful, are also converted to the western view of religion and history.

The fact, however, is that the number of Muslims belonging to the western civilization is very small. Of the total Muslim population, perhaps no more than 5 percent has had western education. Of these perhaps only one or two percent accept the west's world view and the western civilization's claim to be leading mankind towards 'progress' and ultimate 'happiness'. Those who do are the thin veneer of the ruling classes who in fact represent the penetration of the Ummah by its hostile environment. Apart from this small group, largely urban and alienated, it is fair to assume that all other Muslims belong to the Islamic movement.

Nonetheless, there is a need for a more positive test of the Muslims' commitment to the Islamic movement. This can be tested by two simple questions: would the Muslims prefer to live in an Islamic State rather than in a secular nation-State? And are the Muslims prepared to fight, and if necessary die, in the struggle to establish an Islamic State?

Here our concern is only with the attitude or the state of mind of the Muslims. If we can confidently hypothesize that, in the active subconscious of nearly all Muslims, the Islamic State is a goal for which they would be prepared to participate in a struggle, then we have an Islamic movement of nearly one thousand million Muslims. Our discussion of the political culture has made it clear that the post-colonial order has taken no roots in traditionally Muslim societies. Nationalism has succeeded only as a short-term expedient against imperialism, but beyond that the national sentiment has made no lasting impression. The attempt of the Islamic parties to produce a successful mix of nationalism and Islam has also failed.

Islam is from the beginning populist. It creates a 'will' of the people which is in line with the Divine Will, and then creates a State and its institutions to exercise authority on behalf of the Creator and His Creation. In the original Islamic movement led by the Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace, every Muslim took part. Every Muslim also participated in the institutions of the State. The emergence of a ruling class under Banu Umaiyyah and Banu Abbas was the original deviation from the path of the khulafa al-rashidoon. Nonetheless, most 'dynasties', perhaps in their own selfish interests, remained close to the people and the values of Islam. They may not have created the type institutional arrangements for popular consultation that are found in the Constitution of Iran drawn up after the Islamic Revolution, but they kept in close touch with the people, and retained the traditional minimal trappings of the Islamic State and the khilafah. The clear preference of the thousand million Muslims of the world today for the Islamic State is the critical dynamic factor in the Islamic movement. The Islamic movement is clearly an open system. It enjoys all the advantages of an open system. Analytically, the most important parts of the Islamic movement are the community groups organized around mosques throughout the world.

Every mosque is part of the Islamic movement, even the ones that display notices prohibiting 'political discussions'. There are also mosques that admit only those who follow a certain sectarian position. In most of the Arab world the mosques, all waqf (trust) properties, are controlled by the government. The governments appoint staff, including imams, and ensure that the faithful use the place only for going through the motions of ritual prayer. In many cases the imams are not allowed even the freedom of the Friday khutbah (oration). The khutbah is written in the Ministry of Religious Affairs and handed down to the imams to read, parrot-fashion. In some parts of the world (such as Pakistan, India and Bangladesh) mosques are usually controlled by committees of local elders. At key moments during the British raj, and in the period of secular nationalist governments after 'independence', the mosques have played critical roles. In Iran the Islamic movement that brought about the glorious Islamic Revolution was based in the mosques.21 The importance of the mosques is realized by secular authority. Saudi Arabia has given vast sums of money to anyone prepared to build a 'Faisal Mosque' or a 'King Abdul Aziz Mosque'. Recently Saddam Hussain, the Ba'athist President of Iraq, has paid for a mosque to be built in the second largest British city, Birmingham, to be called the 'Saddam Hussain Mosque.' The Saudis recently gave $60,000 for a mosque to be built in Christchurch, New Zealand, on condition that it would have nothing to do with those supporting the Islamic Revolution in Iran.22 There are large prestigious mosques and 'Islamic centres' in such cities as London, Washington, Paris, Ottawa, and Johannesburg financed and controlled by Saudi and other rulers. The importance of mosques is clearly all too obvious to the secular rulers, who are trying to neutralize their influence not only in the Muslim world itself, but everywhere where Muslims live. The Rabitah al-Alam al-Islami (Muslim World League), a Saudi front organization which hands out cash patronage to mosques, 'Islamic' organizations and 'Islamic leaders' all over the world, has also established a 'Supreme Council of Mosques' which holds regular conferences in Makkah. Another Saudi front organization, Dar Al-Ifta, with headquarters in Riyadh, provides patronage to mosques by sending out 'qualified' paid imams. The Dar al-Ifta also sends out 'preachers' to many parts of the world, including Europe, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Perhaps not surprisingly the Saudi-paid 'preachers' uphold Saudi Arabia's claim to be an Islamic State. Such 'preachers' become local community leaders. One of their functions is to send regular reports to their paymasters in Saudi Arabia.

This being the importance of mosques, how many mosques are there in the world today? The question is of great significance to the Islamic movement. There is, of course, no central record of mosques. In the countries where all mosques are controlled by the governments, perhaps records exist. In other countries no such figures exist. In 1967 the Pakistan government estimated that there were 40,000 mosques in West Pakistan alone, or roughly one mosque for every 1,500 of the population. This seems high, but is probably correct. But even if there was only one mosque for every 5,000 Muslims throughout the world, there would still be 200,000 mosques. This seems a very likely figure, perhaps even on the conservative side. The largest of these mosques are situated in the largest Muslim cities, such as Istanbul, Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad, Tehran, Lahore and Delhi. Most of the larger mosques are controlled by secular governments and effectively denied to the Islamic movement. The smallest exist in remote villages and in the narrow back streets of urban centres. If the Ummah may be compared with an army of a thousand million, it has 200,000 mosques to be used as fortifications, dugouts, outposts and centres for training, resistance, organization and communication. All these mosques are currently in use for five daily prayers and most are filled to capacity on Fridays. Fieldwork in Pakistan in 1969-70 showed that as many as 80 per cent of the adult male population in cities attended the Friday prayers. This figure is probably higher in some Arab countries. Interviews in Pakistan also indicated that at times of political turmoil or war attendances in mosques went up considerably. Many imams reported doubling of attendances at the daily prayers, especially for maghrib and isha, during the 1965 war with India. During the latter part of the 'Pakistan movement' (1940-47) in British India, when tension between Muslims and Hindus ran high, para-military Muslim groups emerged spontaneously all over India. These groups used mosques as meeting places, training and communication centres, and for launching vigilance patrols. The network of mosques in Iran has clearly played a major role in the Islamic Revolution there. This role was important when the Pahlavi dynasty's American-supported power appeared invincible and unchallengeable. Slowly, over many decades, the mosques infused the people with love for Islam and hate of the western political and cultural domination that was promoted by the regime. The final outcome has been a Revolution so powerful that it has shaken the whole world. In the prolonged struggle with the forces of counter-revolution in Iran, the mosques appear to have played an equally decisive role. The mobilization of the Muslim masses into a dynamic Islamic movement is the easiest of all revolutionary steps to take, provided the leadership is also revolutionary and totally Islamic. This mobilization has not been achieved and cannot be achieved by 'Islamic parties' operating in the existing political systems and trying merely to manipulate the system in the name of Islam. The mosques will become mobilization points of the Islamic movement when the movement is totally committed to the overthrow of the influences of the western civilization, the post-colonial order, and the establishment of Islamic States.

The mosques are the 'populist' centres of the Ummah where the 'will' of man submits itself to the Will of Allah on a permanent basis. The mosques are also the base on which the pyramid of the Islamic movement, and the Islamic State, is built. In the absence of the movement or the State or both, the mosques remain dormant and are reduced to centres of ritual prayers. In the earliest period of Islamic history mosques were built to consolidate the gains of Islam and to act as forward bases for Islam's rapidly spreading political and military power. Everywhere the Muslims arrived, as traders, preachers or conquerors, the first thing they did was build a mosque. The 'forward base' role of mosques is crucial to the understanding of Islamic history and the political culture that developed in its wake.

There is, however, another role the mosques have played. In their era of defeat and retreat from the stage of history, Muslims have built even more mosques. Whenever they had nothing else to do, they built mosques. In the era of rapid expansion and consolidation the mosques were points of forward movement; as the European colonial era spread across the Muslim societies, Muslims built more mosques as acts of defiance and as points of last retreat. In the hundred years of British rule over India, for instance, the Muslims of India built more mosques than they had done in the six hundred years for which they had been undisputed rulers of India. The proliferation of mosques in the era of defeat and humiliation is also the act of defiance of a broken people. Every new mosque strengthens the foundations of the Islamic movement. Once a small Muslim community is consolidated around a mosque, it is only a matter of time before the mosque and the community links up with the larger, global, Islamic movement.

The hypothesis of the Islamic movement consisting of a thousand million Muslims is, therefore, rooted in history and in the careful observation of contemporary behaviour, both in victory and in defeat. This is no longer an hypothesis; it is an uncontestable fact. The west's failure to erode the basic commitment of the Muslims to Islam is now widely recognized.

The mosques, though often organized as auqaf with written constitutions and procedures, are generally open systems. Their structures and hierarchies are flexible in the extreme, except where the mosques are controlled by governments. This open quality makes the mosques the ideal network for the Islamic movement. In countries where mosques are controlled by the secular State, the mosques remain open systems. The presence of State-appointed imams and other staff will not prevent the use of the mosques as centres once the Muslim populations around them become activated by the Islamic movement. The imams and other staff are likely to join the general body of Muslims in the struggle against secular authority and foreign influence.

Apart from the mosques, and madrassahs associated with them, the Ummah today contains a large number of 'closed' systems, many of them calling themselves 'Islamic'. We have already discussed and excluded the nation-States from the Islamic movement.23 The nation-States have also created a large number of 'Islamic' organizations primarily designed to protect the secular States and their rulers from Islam. These organizations exist at all levels, from local to international. The Organization of the Islamic Conference (the Islamic Secretariat) and all its affiliates are of this variety. State sponsored national bodies performing 'Islamic' functions are everywhere. The latest craze is for 'Islamic universities' and 'Islamic banks'. In recent years the Saudis have financed large 'Islamic councils' in Asia, Europe, Africa and North America to project their Islamicity. The same network of 'Islamic councils' is also used by Egypt, the Gulf States, Pakistan and many other centres for the operation of their largely mercenary 'Islamic workers'. These councils try to buy out the local leadership of Muslim communities by donations and all-inclusive trips to various 'Islamic conferences' all over the world.

In the private sector the situation is not much better. The western-educated professional class of lawyers, doctors, engineers, accountants and business magnates has discovered that involvement in some 'Islamic work' is good for their public image and for business. Some verses of the Qur'an hung around offices and homes, some well-publicized donations to 'Islamic causes', and membership of some religious 'trusts' are the obvious ways of pinning Islam to the individual or his business masthead. Most of this is misleading, though some is also genuine in the sense that the understanding of those engaged in this kind of activity is limited to this type of conventional behaviour. They do not consciously set out to use 'Islamic work' for personal advantage; it just works out that way. A good many careerists use Islamic organizations for the promotion of their selfish ends. These individuals and their 'Islamic organizations' are everywhere. It is tempting to regard them all as beyond the pale of acceptable behaviour in the Islamic movement. The time for such a drastic step is not yet, though it may well come soon. At present it would be prudent to allow them time and give them the opportunity to realize the error of their ways. There is obviously going to be a polarization of positions between those 'Islamicists' who regard the nation-States as Islamic enough and capable of 'Islamization', and the Islamic movement committed to the total rejection of these left-overs of recent history and to the establishment of new Islamic States in the only way possible following the method of the Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace. As the new position gets stronger the old positions will weaken. Many nominally Islamic organizations and individuals associated with them will realize the true nature of the company they have been keeping and move to the new position. Only the most rabid careerists, time-servers and sycophants will be left. That will be the time to exclude them firmly from the Islamic movement. As the polarization goes further, the hidden hand of the secular rulers and their political systems will begin to exercise greater direct control over their traditional areas of 'Islamic' influence. This will expose the true nature of these organizations and of the careerists associated with them.

The size of the Islamic movement, therefore, is the entire Ummah knit together by the network of mosques and other organizations throughout the world. This should not divert our attention from the fact that the basic unit of the Islamic movement is the Muslim individual, and that there are one thousand million of them.

The relationship between the Islamic State and the Islamic movement is an area which has so far received little attention. This is because once the Prophet, upon whom be peace, had established the State in Madinah, the State and the movement became one and the same thing. The Islamic State was the movement, and the person of the khalifah was the centre of allegiance. The principle of allegiance to the khalifah was so central to the cohesion of Islam that even the imamiyyah group among the Muslims, who later became known as the Shi'a, though in fundamental disagreement with the course the succession to the Prophet had taken, took care to give allegiance—bai'ah—to the khalifah.24

Ali ibn Abi Talib himself accepted the three khulafa before him and served under them. When he became khalifah, he did not change the title of the office of the head of the Islamic State to imam. Hasan ibn Ali, who succeeded his father in the khilafah, eventually accepted his father's old adversary, Mu'awiyyah, as khalifah and gave his own and his followers' allegiance to him. Husain ibn Ali refused allegiance to Mu'awiyyah's son, Yazid, and was martyred at Karbala. It is significant that to this day there is no difference between the Shi'a and the Sunni over the rights and wrongs of the Karbala tragedy. Imam Husain and his family are respected as shuhada by all Muslims and considered models of Islamic resistance to tyranny. All the subsequent imams of the imamiyyah tradition offered their own and their followers' allegiance to the Umaiyyad and Abbassid khulafa. In later history, when the far-flung areas of Islam became autonomous States, the local sultans and rulers took care to have their authority verified by the khalifah in Baghdad or in Istanbul. The abolition of the khilafah broke the last political link that held the Ummah together, though the link had become largely symbolic. The nation-State order, with each State 'sovereign' in its own right, is the west's, and the westernized Muslim elites', prescription for the permanent dismembering of the Ummah. It will be a long time before the Ummah is linked together again by a single central authority.

The unity of the Ummah in the meantime is held together by the Ummah's role as the Islamic movement. The Islamic movement, as demonstrated in earlier discussion, has the network of mosques, political culture, common memory and shared expectations necessary to hold it together until a higher stage of cohesion is reached. The highest stage of cohesion is of course the Islamic State. The entire Ummah will not reach this level of cohesion at once. Progress will be uneven and often difficult. At the present time the Islamic movement in Iran has already brought about an Islamic Revolution and an Islamic State has been established within the territories of the former Iranian nation-State. In Iran alone has the complete merger of the Islamic State and the Islamic movement been achieved. There the State is the movement, and the movement is the State. This is the configuration between the State and the movement first established in the earliest history of Islam. This would also be the ideal situation if Iran were the entire Ummah. The fact, however, is that Iran is a very small part of the Ummah and of the Islamic movement. Only 40 million Muslims live in Iran whereas the Ummah consists of a thousand million faithful.

There is, then, a new situation that has not existed before: the emergence of an Islamic State in a small area of the Ummah. A relationship between the Islamic State and the worldwide Islamic movement has to be forged. The two have to become partners in the task of making the history that lies ahead. The geographical Islamic State and the Islamic movement without boundaries are in fact indispensable to each other. The Islamic State, in the final analysis, cannot be confined to or defended within a geographical area. Even when, as now, the Islamic State is limited to a small geographical area it must be defended by Muslims all over the world. The military defence of the Islamic State is only a limited form of defence. The ultimate defence of the Islamic State lies in the State's ability to identify itself with the global Islamic movement and the Ummah's commitment to protect the Islamic State. The Islamic State has advantages of mobilized resources and centralized institutions which the Islamic movement lacks, but the Islamic movement has the flexibility, diversity, versatility and all the other advantages of an 'open system' which are of great value to the Islamic State. Once the 'open system' of the Islamic movement and the mobilized resources of the Islamic State have been brought together, the result will be a partnership as powerful and invincible as history has ever known. The forging of such a partnership between the Islamic State and the Islamic movement is the greatest single task of our time. Once this initial partnership has been established other Islamic Revolutions and new Islamic States will inevitably follow.

1. My own 1976 monograph, The Islamic Movement: A Systems Approach (London: The Open Press, 1976) was an early example of such hypothesising. As long ago as 1945, the late Maulana Maudoodi delivered a speech on 'The Moral Foundations of the Islamic Movement' (Tehrik-e Islami ki Ikhlaqi Bunyaden). This speech has been published by Islamic Publications, Lahore and Dacca, in various editions.

2. In 1976, the 'Concerned Muslims of Berkeley' began publishing a journal called Al-Bayan. It ceased publication in 1978.

3. For a definition of the Islamic movement, see my paper 'The Islamic movement: setting out to change the world again' in Issues of the Islamic Movement 1980-81, London and Toronto: The Open Press, 1982.

4. Al-Qur'an 5:3.

5. Al-Qur'an, Surah 110.

6. Quoted in Kalim Siddiqui, Beyond the Muslim Nation-States, London: The Open Press, 1977, p.3.

7. Abul Ala Maudoodi, Khilafat-wo-Malukiyyat, Lahore: Idara-e Tarjamanul Qur'an, various editions since 1966.

8. Al-Qur'an 2:256.

9. Al-Qur'an 8:73.

10. Daily Jang, London, February 2, 1980.

11. I was present at this press conference.

12. These Ikhwan factions have been disowned by such other leading Ikhwan figures as Essam al-Attar, who lives in exile in Germany.

13. See the author's guest editorial 'The liberal soft centre in the Revolution' in Crescent International, May 1-15, 1981, also in Issues in the Islamic Movement 1980-81, op. cit., p.300.

14. Richard P. Mitchell, The Society of the Muslim Brothers, London: Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 47-71.

15. See, for example, Khurshid Ahmad's letter in Impact, London: February 9-22, 1973, in reply to my article 'Whose failure in Pakistan?' in Impact, December 22, 1972-January 11, 1973.

16. See Kalim Siddiqui, Conflict, Crisis and War in Pakistan, London: Macmillan and New York: Praeger, 1972.

17. Ruhullah Khomeini, Islam and Revolution, translated and annotated by Hamid Algar, Berkeley: Mizan Press, 1981, p. 302.

18. Al-Qur'an 4:59.

19. Khomeini, op. cit., p. 345, n.13.

20. For a more recent discussion of Shi'a-Sunni issues, see Hamid Enayat, Modern Islamic Political Thought, London: Macmillan, 1982.

21. Hamid Algar, The Islamic Revolution in Iran, London: Open Press 1980. [Later reissued as Algar, 'The Roots of the Islamic Revolution', London: The Open Press, 1983.CEd.]

22. The author learnt of this on a visit to New Zealand in May 1982. In Wellington, the wife of the Egyptian ambassador, a lady who obviously takes good care of her figure and turns up in the mosque in tight trousers and long, open, flowing hair-styles, gives Qur'anic lessons there!

23. See also my paper 'The Islamic movement: setting out to change the world again', op. cit. In earlier writings, I was prepared to accept the Muslim nation-States as 'sub-systems' of the Islamic movement. See, for instance, my paper The Islamic Movement: A Systems Approach, op. cit.

24. Al-Kulayni, Al-Kafi, vol. 1, Kitab ul-Hujjah.