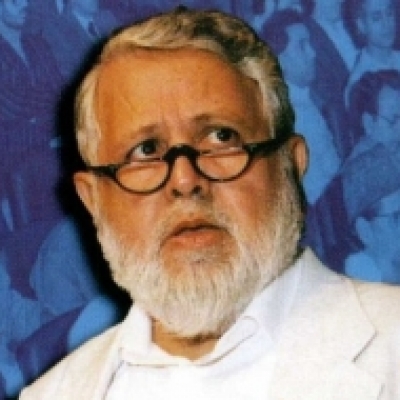

Kalim Siddiqui

Kalim SiddiquiThis paper was written by Dr Kalim Siddiqui just before his untimely death in April 1996. It was published in 1998 by the Institute of Contemporary Islamic Thought (ICIT), Toronto and London, inviting Muslim scholars, academics and activists to work on the Seerah of the noble Messenger (saws) from this new, analytical perspective rather the mere descriptive approach hitherto taken with Seerah studies.

…A messenger reciting unto you the revelations of Allah made plain, that he may bring forth those who believe and do good works from darkness unto light. (Al-Qur’an, 65:11)

This how Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala describes the Prophet, peace be upon him, in the noble Qur’an. But the point is addressed not only to his contemporaries, but also to all people in times yet to come. This is why he was the Last, or Seal, of all Prophets [1]. Prophethood ended with Muhammad, upon whom be peace, because his Seerah could be applied by ‘those who believe and do righteous deeds’ at any time and place in history and would lead them ‘from the depth of darkness into light’.

The ‘depth of darkness’ today is represented by the West and the Western civilization on the one hand, and the conditions into which Muslim societies have sunk on the other. This is the modern equivalent of the state of jahiliyyah which confronted the great Exemplar [2]. And this contemporary darkness is total because the Western civilization encompasses the whole world. It is everywhere. The Islamic Revolution in Iran has made a bold attempt to escape this darkness and to move into light, but the experiment is still in an early phase.

There is no doubt that the rest of the Ummah today remains immersed in ‘the depth of darkness’ in every conceivable way. This darkness has spread to include everything from the individual behaviour of Muslims to their collective condition, identity and behaviour. Merely to describe the condition of the Ummah today would require many volumes of thoroughly researched books. A simple way to achieve the same result is to say that Muslims today have reverted to the state of jahiliyyah, or darkness (zulumat), without formally stepping out of Islam. Thus, once again, we are faced with the same problem that faced the great Exemplar himself, upon whom be peace. And, clearly, the only way forward is to follow the Seerah and the Sunnah of the Prophet.

But the issue—how to follow the Seerah and the Sunnah of the Prophet?—is not so simple. In today’s conditions the Seerah cannot be followed in the shape and form in which it is recorded in the classical texts on the subject. The Seerah and the Sunnah, like the Qur’an, are sources of knowledge and guidance for all times. The Seerah is there to be researched, written, understood and applied in each new historical situation as it emerges. In recent times a variety of Islamic movements have emerged, claiming to be based on the Seerah. But the results they have achieved have varied from the dubious successes of most of the ‘Islamic parties’ that emerged during the colonial period to the recent triumph of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Perhaps each new generation, in each new historical situation, has to apply the Seerah afresh according to its peculiar circumstances and requirements. Perhaps a process of trial and error is inevitably involved in recapturing the ethos of the Seerah in today’s conditions.

It is also possible that the historical situation and the intellectual climate of the time when the first classical works on the Seerah were compiled imposed their logic, limits and needs on such works as those of Ibn Ishaq, al-Waqidi and Ibn Hisham. The politically dominant position of Islam, indeed the geographically expanding dominion and power of Islam, were taken for granted as part of a divinely ordained plan. This persuaded the early compilers of the Seerah to concentrate on issues of the personal qualities of the Prophet, upon whom be peace, and the taqwa (piety) of early Muslims. They followed the simple historical method of compiling a chronological record of events with great accuracy. There was no attempt to link early events with later events, or to discover patterns in the Seerah as guides to the underlying methods used by the Prophet, upon whom be peace.

Significant in this connection is the use of power. Power relationships are the basis of all relationships in nature. Power inequalities are inherent in the state of nature itself, and defining factors in determining behaviour. Stronger animals eat or otherwise exploit the weaker and the weakest try to seek refuge underground or in thick undergrowth. The Qur’an describes mankind as the best of Allah’s creation [3]. This means that mankind has been given the power or ability to acquire control over all things. Man can also have power over other men, and rulers can replace other rulers.

Allah has promised, to those among you who believe and work righteous deeds, that He will, of a surety, grant them in the land inheritance of power, as He granted it to those before them; that He will establish in authority their religion—the one which He has chosen for them; and that He will change (their state), after the fear in which they (lived), to one of security and peace; ‘They will worship Me (alone) and not associate aught with Me.’ If any do reject Faith after this, they are rebellious and wicked. (Al-Qur’an, 24:55)

Perhaps what is wrong with the modern world is that human relations are defined almost purely by real or perceived power considerations. The powerful impose their will and their interests on the weak. The weak generally submit to those with more power. Clearly when human behaviour is determined purely by power differentiations, there can be no justice (‘adl); husbands will oppress their wives, employers their employees, monopolistic suppliers will impose unjust prices on customers, officials will oppress their juniors, rulers will oppress their people, and strong States will bully, invade, occupy or impose unjust ‘treaties’ on weaker States. Islam achieves justice by regulating the use of power in all relationships. Islam does not equalize power; that would be against the state of nature. No order would be possible without power differentiation. But what Islam does is that it places strict limits and moral codes on the exercise of power at all levels.

They are those who, if we establish them in the land, establish regular prayer and give zakat, enjoin the right and forbid wrong; with Allah rests the end and decision of all affairs. (Al-Qur’an, 22:41)

Permission is also given for the weak to fight their oppressors [4]. The Prophet’s use of power and the limits he placed on the use of power are a rich source of new research [5].

The Seerah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace, is also a model for the acquisition and use of power. At birth Muhammad was an orphan. He grew up unable to read or write in a society which had a highly developed language and where literary and cultural symposiums were regularly held. But they were divided into tribes and misused their power even among themselves and against the weakest in their society; for example, blood feuds among tribes lasting over many generations were common, and female children were buried alive. Tribal leaders and elders wielded enormous power which they mostly misused against their own people, families and neighbours, and by spilling the blood of the innocent. There was little moral or political framework to regulate the power of those in authority.

In this environment the Prophet began life without any claim to power. When he died he had achieved unchallenged power and built a power base, the Islamic State, that was to demolish all other centres of power. What was this power and what was the source of this power? The power the Prophet sought and achieved was not power to rule and oppress or to invade and lay waste other lands and peoples. His power was not in numbers of men, or material or territory at his disposal; the secret of his power lay in the belief, commitment and obedience of the men and women around him.

The whole of the Seerah can be written, read and understood in the framework of the Prophet’s acquisition and use of power. The fact that this has not been done is one of the great failures in the intellectual and political history of Muslim scholarship which the Islamic movement must immediately redress. Research must now be begun to define power in the Seerah, to identify the methods for the acquisition of power, and to draw up principles for the use of power. To do this, some scholars will also have to attempt to draw a profile of the political structures created by the Prophet within which the power of Islam resided. This opens up the whole issue of leadership and the limits of power, if any, that the leadership must be subjected to. Did the Prophet limit his own power? Did he share power? Did he use shura as a method of decision making? Examples of these will have to be found in the Seerah and thoroughly researched. What is needed is not mere description of what happened; we need to analyse each situation and try to compare it with similar situations at other times in the Seerah. We have to answer these and many more similar questions; and we have to conceptualize our answers in such a way that when the concepts are applied to the Seerah as a whole the results are consistent.

Immediately following the issue of power is the issue of the definition of ‘politics’. Once again we are in a minefield of conflicting ideas. Can we separate the meaning of ‘politics’ in Islam from the general meaning that this term has come to have in the modern world under the influence of the West? This issue cannot be resolved by simplistic affirmations, such as that politics in Islam is moral while politics outside Islam is immoral. There is something more to politics in the Seerah than ‘politics based on morality’. How can it be defined or, at least, delineated? Is there a consistent pattern in the Prophet’s political conduct from the beginning to the end? If so, what are the principles and rules of politics in the Seerah?

Muslims of all schools of thought have always regarded the ‘Islamic State’, or the khilafah, as the physical structure and the ultimate manifestation of Islam. It is also agreed that the Prophet, upon whom be peace, established the first Islamic State in Madinah. As such, the Islamic State established by the Prophet, upon whom be peace, is an integral and inseparable part of the Seerah of the Prophet. Yet the State of Madinah is not included as such in the classical Seerah literature. Only in relatively recent, politically-motivated literature on the Seerah has attention been given to the State of Madinah. In fact the duty to establish the Islamic State is as much part of the Muslims’ obligatory ibadah as salat, saum, zakat, hajj and so on. This obligation cannot be suspended or modified under any circumstance.

O ye who believe! Obey Allah, and obey the Messenger, and those charged with authority among you. (Al-Qur’an, 4:59) [6]

There is evidence that even in Makkah, from the earliest stages of his mission, the Prophet organized the small Muslim community on the lines of a State. He dealt with the mushrikeen of Makkah and with the Negus across the Red Sea as the leader of a political entity called Islam. This is an important area of research from which scholars could begin to trace the power of Islam in order to define it. To confine our understanding of political power to something that only a territorial State can possess may be one of the mistakes that modern Muslim political thought has made under the influence of the West. It is possible that power is an all-pervasive quality of Islam related to the belief and taqwa of Muslims individually and collectively, whether or not they have control over a territory. If so, this would have enormous implications for the Islamic movement and Muslim minorities throughout the world. It would then be possible to mobilize the power and resources of Islam in small groups as well as in great States and Empires. If so, relatively small groups of Muslims, living together or living far apart, may be able to successfully assert and exert the power of Islam using today’s information technology and organizational skills.

Nor can we ignore the fact that the Islamic State and the quality of its leadership have played a crucial part in history. We can argue that the moral foundations of the Islamic State were shaken soon after the demise of the Prophet, upon whom be peace. This took the form of the introduction of malukiyyah [7] from the beginning of Umayyad rule. The continuation of dynastic rule, in one form or another, albeit in the name of Islam, ultimately led to the defeat and dismemberment of dar al-Islam at the hands of the European colonialists. Muslim historians have shied away from researching and identifying the processes of decline and defeat that were implicit in malukiyyah as a form of government and leadership. This gap in our knowledge must now be filled.

European colonial rule over all parts of dar al-Islam and its partition into more than fifty weak and subservient nation-States has created an unprecedented situation. To emerge from this predicament and reintegrate the Ummah requires fresh insights into the Seerah and the political methods of the Prophet, upon whom be peace. A great deal of descriptive, analytical and prescriptive political thought has been written in the last one hundred years. The results range from the minimal or nominal participation in secular government of ‘Islamic parties’ in such countries as Egypt, Turkey, Malaysia, Pakistan and Sudan, to the victory of the Islamic Revolution in Iran. There is also the victory of the mujahideen in Afghanistan, followed by a bloody civil war among competing groups, some calling themselves ‘Islamic’. The decline of Muslim power, then the total loss of Muslim power, followed by Western sponsored nationalism in new Muslim nation-States and the rise of incipient ‘Islamic parties’ and ‘movements’, offers a rich source for checking historic results with the Seerah. In this important area researchers have to come up with answers and insights from the Seerah not sought after before. This era may be described as the era of neo-jahiliyyah. Can modern nationalism be equated with tribalism of the time of the Prophet? If so, how did the Prophet, upon whom be peace, deal with tribalism? When the mushrikeen of Makkah made the removal of those who were not racially Arab a condition of their joining Islam, the Qur’an was emphatic:

Send not away those who call on their Lord morning and evening, seeking His Face. In naught art thou accountable for them, and in naught are they accountable for thee, that thou shouldst turn them away, and thus be (one) of the unjust. (Al-Qur’an, 6:52)

Can Muslims today deal with nationalism in the same way as the Prophet dealt with tribalism? What likelihood is there of civil wars breaking out in different parts of dar al-Islam between nationalism and Islam? Are such civil wars inevitable or perhaps even desirable? What will be the implications of such wars, including the near certainty of external intervention? Maybe such civil wars are already under way at low levels in many Muslim countries? Does the Seerah point to the inevitability of armed struggle between the Islamic movement and the nationalist, secular, post-colonial élites? If so, what steps have to be taken to minimize the intensity of armed conflicts among Muslims and between Muslims and non-Muslims? What are the rules of engagement in such armed struggles? [8]

Then there is a whole range of modern political concepts, with their origin in the political history, experience and philosophy of the West, that have found their way into everyday usage in Muslim political thought and vocabulary. These include such concepts as democracy, representative government, elections, multi-party systems, pluralism, socialism, communism, capitalism, equality, freedom of speech, emancipation of women and so on. Each of these needs to be closely scrutinized in light of the Seerah and, if necessary, totally rejected and repudiated. This exercise is essential if Muslims are to produce their own conceptual tools for the reordering of Muslim societies. It is not enough to assert that Islam and Western civilization are incompatible; this incompatibility has to be demonstrated within the framework of the Seerah. We need to develop and present a complete outline, indeed a detailed map, of the alternative civilization of Islam. This is perhaps the most important challenge facing Muslim scholarship today.

This leads us to the crucial issue of opposition. The opposition to the Prophet, upon whom be peace, was no less total and vicious than the opposition the Islamic movement confronts in its attempt to create, or recreate, a global civilization today. The West is already opposing, with all the cunning and might at its disposal, even the minor political goals currently pursued by Islamic groups in many parts of the world. A total statement of the political goals of Islam in terms of the Seerah is certain to attract total opposition from the West, and the agents of the West in Muslim countries [9]. To deal with this situation, the Seerah has to be studied to produce the defensive and offensive strategies of Islam at every stage of this global confrontation over a very long period of time. We must also recognize that there may be no precedent in the Seerah for certain current situations. The best we can hope for in these situations is to apply qiyas, the principle of analogical inference.

Then there are the great issues of morality and economics mixed together. How will Islam redistribute the resources and wealth of the world? How would this affect capital formation and investment? Is there a limit to growth? Is such a limit desirable? What minimum standards of living must be provided for all before the few can be allowed to add to their already lavish living? How can the West be stopped from using Asia, Africa and Southern America as a hinterland to be exploited for the benefit of the rich northern hemisphere around the North Atlantic? The West’s role in the modern world perfectly fits the description in the Qur’an as ‘mischief on earth’ [10]. In what way might the Seerah guide us in these vital contemporary issues of social disorder, iniquity and injustice?

All the issues relating to corporate capitalism, paper currency, banking, interest, exchange rates, capital formation and investment need to be tackled. A whole body of literature has emerged under the general title of ‘Islamic economics’. By and large, it is similar in character to the political literature of the ‘Islamic democracy’ variety. Essentially it is an attempt to import into Islam all the West’s economic and political experience. In recent years it has become clear that the West’s drive for the wholesale economic and political exploitation of the world will inevitably lead the world to the brink of ecological and environmental disaster. This brings us back to the mutual incompatibility of Islam and the West, and all the issues raised by this basic clash between the two. Answers to these questions have to be sought in the study of the Seerah.

It has to be admitted and realized that some of these issues have never before been raised in the context of the Seerah. Therefore, much of the early work on these issues will be exploratory and tentative. This is inevitable. But the publication and debating of such exploratory work will then generate new research and thinking, leading to new ideas and higher quality literature in the future. The fact is that Muslims have never explored the Seerah to find answers to some of the questions raised in this paper; at this stage we can only hope to make a start in this direction.

The major objectives of the new research required on the Seerah can be summarised as follows:

Once the long process of applying the Seerah to achieve convergence of Muslim thought on current issues is begun, we must avoid the sort of theological disputations which have led to obscurantism and bitterness among the various schools of thought in the past. Such issues are now, for all practical purposes, dead or at least irrelevant. New ideas require a new and open approach. The new ideas thrown up by an open-ended study of the Seerah can then be applied and the results checked against the Seerah. The Seerah then becomes a dynamic paradigm for new ideas, actions and results. These new ideas can then be refined and modified and applied again to achieve results at any particular time and place. This process should become a permanent process for shaping history, for creating new Islamic societies, for establishing new Islamic States, and so on, indefinitely into the future. In this way we shall have made the Seerah a permanent source of new ideas, hypotheses, and policy options. It is only when Muslims have learned to use the Seerah as an active guide in contemporary history at every step that they shall have achieved the full potential of the Seerah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace. This will not necessarily mean success at every step; even the Prophet experienced occasional failure. But what it could do is to minimize the rate of failure and facilitate the evaluation of the causes of failure and thus the revision of policy. A political system based on the Seerah should be stable and long lasting. It will facilitate the continuous emergence of broad public consensus on major issues and offer a framework for public debate free of acrimony over personalities or party positions.

Below are listed some of the areas in which ulama, scholars, researchers, students, and writers may seek topics for their particular research. By the very nature of the Seerah, and of our problems, such a list cannot be exhaustive. The knowledge we have of the Seerah is already very extensive; the emphasis must now be on seeking new insights from the Seerah to solve the problems now facing the Ummah. For example, if we were asked to name one factor more responsible than any other for our present maladies, we should have to say that it was the lack of power. Therefore, the issue of power, its definition, acquisition and use must occupy a substantial proportion of our attention.

We know that the Prophet, upon whom be peace, embarked on his career destitute of power. He ended his life at the head of a State that commanded overwhelming power over the Arabian peninsula, and had the ability to generate sufficient power to defeat and replace the ‘superpowers’ of the time, Persia and Byzantine. These are feats of history that Muslims have to repeat in today’s conditions. The defeat of the former Soviet Union in Afghanistan, the defeat of the United States in Iran, Vietnam and Somalia, and the defeat of Israel in Lebanon are glimpses of what is possible under even the most imperfect conditions. Clearly, if conditions improve, a great deal more can come within our reach. Drawing up the outline and detailed map of an alternative civilization, based on the Seerah, is not an exercise in futility. It is the logical next step on the road to the recovery of Islam and the Ummah from our own dark ages of defeat, dismemberment, and subservience to the power of kufr.

The early sources of Seerah in the Arab cultural traditions of the time form a fascinating study. The verbal tradition of stories and poetry led to Ibn Ishaq’s full-scale Seerah and al-Waqidi’s Maghazi, among many others. We are not concerned here with that period; what we want to know is in what ways the decline of Muslim power has affected and influenced the study and writing of the Seerah and Sunnah of Muhammad, upon whom be peace. We are clearly not the first to seek solutions to our modern problems in the Seerah. Uthman dan Fodio established the Sokoto Caliphate in West Africa in the early part of the 19th century. He, his family and followers are said to have followed the method of the Seerah, including hijrah, in a struggle that also included jihad. There are many more similar figures throughout the last two hundred years who in seeking to resist the power of the West drew on the Seerah for their inspiration and methods of struggle. Literature written by them or about them is of crucial importance, and needs to be critically analysed. Some very recent literature in such languages as Turkish, Urdu, Bengali, Malay, English and Hausa appears to be influenced by the Islamic Revolution in Iran. How far and in what ways the Seerah has influenced developments in the Shi’i tradition leading up to the Islamic Revolution is also a question clamouring for attention. A survey of Seerah writings over the last 200 years might produce insights into how the Seerah has influenced Muslim political and religious thought during a period of rapid decline of Muslim power.

The finality of the Prophethood of Muhammad ibn Abdullah, peace be upon him, is a key part of the aqida of all Muslims [11]. As aqida, it needs no restatement. But there are certain implications of this fact for history and for the evolution of Muslim thought, especially Muslim political thought. For example, the fact that no new Prophet is to come and that direct revelation (wahi) has been completed for all time, puts great emphasis on the Seerah. It is the Seerah, the living manifestation of the Qur’an, that is the key to the Qur’an as well. This is why the Seerah is sometimes described as the first tafseer. Scholars may wish to explore all the implications of this. It surely means that Muslim divergences from the roots of Islam can only be small and temporary; that Islam has an in-built versatility, magnetism and mechanism to guide Muslims back to itself after long periods of divergence. We can also learn a great deal about the nature and limits of Muslim divergences. We can also learn about the nature of Muslim attempts to return to the roots of Islam and the historical processes that may be involved. There is also the important issue of structural impediments that Muslims and Islamic movements face in their search for correction of their thought processes and political programmes. The obvious examples of these structural impediments are nationalism and nation-States, as well as the secondary theological positions—often deviant—that have been taken up by various schools of thought and religious traditions in many parts of the world. This is not to deny the importance to Muslims of developing dynamic intellectual traditions within the bounds of the Seerah at all times in history. We need guidelines for the growth and flowering of such intellectual traditions at different times in history, or in different parts of the world at the same time.

Islam faced intense opposition from the beginning of the Prophethood of Muhammad, upon whom be peace, and throughout the Prophet’s life. The Prophet’s method in dealing with this constant opposition is an integral part of the Seerah. We need to identify and study it, and examine how it can be applied in today’s conditions. Moreover, while the broad outline of this opposition is recorded and described in the Seerah literature, the opposition itself as a phenomenon has not been analysed. Is the opposition to Islam in the modern world essentially a continuation of the opposition to Islam at the time of the Prophet? If so, then we are better equipped to understand the modern hostility to Islam and how best we can meet this challenge.

As the Prophet, upon whom be peace, was the undisputed Leader of his people from the advent of his risalah until the end of his life, the Seerah is clearly a rich source from which to identify the qualities necessary in a leader. The concept of the leader and leadership in Islam as exemplified by the Prophet is also an important area of research [12]. What were the Prophet’s leadership training methods and programmes? The answers to this may hold the key to many of our contemporary problems in the field of education and training. The failure of leadership in the ‘Islamic parties’ may be traced to the systems of education of which they were products. Did the system of education and training in the Shi’i school create the leadership that made the Islamic Revolution possible? What lessons are there in it for systems of ‘Islamic education’ in other parts of the world? This offers a rich area for research.

Leadership in the Seerah also has a strong conceptual base for its continuation after the death of the Prophet, upon whom be peace. There has been considerable controversy on the issue of succession to the Prophet between the Shi’i and Sunni schools of thought. A great deal of ‘secondary theology’ has been written around this subject. We do not need to go over this ground again. But, in the conditions prevailing today, there are signs pointing towards a convergence of Muslim political thought on this issue.

However, one point is particularly important here: the new research done in the framework of the global Islamic movement must focus on areas which minimize differences and expand on the new common ideas on which there is clearly convergence and agreement. Papers written in a sectarian spirit, or presenting a sectarian position, on this issue, or any other issue, are no longer acceptable. We must, in the words of the Qur’an, put our historical differences aside and learn to be ‘compassionate amongst each other’ [13].

An examination of the structure of society in Makkah is important to identify its power structure and hierarchy, and so understand the context in which the Prophet took the decisions he took. There were men in Makkah who wielded great power and influence. The Makkan society also had great weaknesses, rivalries and conflicts. The Prophet’s strategy in dealing with this society, and using Makkan society and its immediate environs, is an essential part of the Seerah. The organization of the small Muslim society in Makkah offers many lessons on how relatively small communities can deal with and win over much larger communities. The first migration to Habasha (Abyssinia) and the negotiations with the Negus may also be examined in this framework.

Clearly the hijrah to Madinah is the greatest single event in the Seerah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace. How he prepared for it is dealt with summarily in the traditional Seerah literature. This event needs to be examined in depth as an underlying method of overcoming great difficulties at one place by building a power-base at another. Clearly the Prophet did not mean to leave Makkah for good; he intended to return as a conqueror or liberator. The steps the Prophet took immediately upon his arrival in Madinah were clear indications of his intention to challenge the Makkan power. That this would involve war was also clear from the Prophet’s early moves in Madinah and the agreements he entered into with the tribes there, who were committed to defend him. Moving out of one’s normal hostile habitat to prepare for eventual return to rule over it is a familiar pattern in history. The Prophet’s use of this method needs very careful handling. There are political lessons to be learned and techniques to be developed for use in today’s conditions.

The first migration to Habasha and the negotiations with the Negus may also be examined in this framework. Did the results of this migration encourage the Prophet, upon whom be peace, to seek and plan for another, greater hijrah, to secure a greater power base outside Makkah? Did this lead to the Prophet’s eventual migration to Madinah? Hijrah as a method of developing an alternative power center needs to be examined in some detail.

This is clearly the heart of the Seerah that we have set out to explore. Power in Islam is not like power in other historical and political situations. Power in Islam does not mean the same thing as in the use of such contemporary terms as great powers, superpowers, regional powers, minor powers and so on. Power in the Seerah has an additional quality over and above all other forms of power. Nothing else can explain the global power and presence that Islam continues to exercise in the world today in spite of hundreds of years of continuous decline and physical defeat. Perhaps the colonial powers succeeded in defeating and destroying the structures in which Muslim power resided. But there is another level of Islamic power that cannot be destroyed by military power. Islam has a regenerative capacity that does not depend on political and military structures. Islam has no political and military structures but has secured its long-term survival in a form of power that remains immune against destruction by physical action, occupation or military invasion. What is this power? How can it be described? What evidence of it is there in the Seerah? The Seerah is also a guide for the reconstruction of the structural foundations and institutions of Islamic power after a period of defeat and dismemberment.

This ability to separate power from its structures is also peculiar to Islam. The process of establishing the Islamic State can be seen as the drive to build new structures for power. All earlier civilizations in history—Chinese, Indian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, etc.—have enjoyed their heyday and then declined, never to reappear. The civilization of Islam is unique in this respect; unique in that it is in the process of regeneration, and unique in that it has the diffuse power base in history that can be used for this purpose. A global Ummah is now committed to this cause, exploring all possible options and exploring the Seerah for guidelines.

These have played an important part in the Seerah. Instances of them are found in the life of Muhammad before he was called to Prophethood. He was known as a man of integrity and honesty. The Arabs called him al-Amin, the trustworthy. He also mediated in and averted a potentially bloody conflict over the rebuilding of the Ka’aba and the placement of the Black Stone. After he became Prophet, he pursued peace with his enemies in Makkah and with the tribes around Makkah. During this period he is known not to have retaliated aggressively against those who tormented him or other Muslims. The Prophet patiently negotiated two pacts of Aqaba that laid the foundations for the hijrah to Madinah. Once in Madinah he entered into a covenant with all the parties in that city, many of them his enemies, including the two Jewish tribes. This social contract in Madinah, known Seerah literature as the Sihafah, is also known as the Constitution of Madinah. It raises many questions. For example, was the Constitution of Madinah designed to neutralize his internal enemies in Madinah against his external enemies, with whom the Prophet expected early wars? The Constitution of Madinah has not been analysed as extensively and profoundly as it ought to be. In the sixth year of the hijrah the Prophet entered into an agreement with Quraish of Makkah, known as the Treaty of Hudaibiyyah. Many of the Prophet’s companions thought the terms were too favourable to Makkans and humiliating to Muslims. The Prophet was, therefore, obviously a man of peace who did not want to fight if he could avoid it; yet, after the hijrah, he had sought an early military engagement with Quraish of Makkah. It can also be argued that peace treaties and agreements that the Prophet entered into with his foes were designed to buy time to accumulate power for the ultimate victory of Islam. Only two or three episodes of this kind are mentioned here; the Seerah offers many more examples. Detailed research and analysis in this area may provide a pattern for the future conduct of the Islamic movement and the Islamic State.

Politics in the modern world is almost universally perceived as a ‘dirty game’. It is also widely regarded as a game ‘to fool all of the people all of the time’. In more serious or academic circles, politics is regarded as a study of the powerful seeking to retain or increase their power in their own State or in their relations with other States. It is a zero-sum game—the loss of one is the gain of another, or the gain of one equals or exceeds the loss of another. It should be noted that siyasah, the Arabic word for politics, does not appear in the Qur’an at all, or in the early Seerah literature. Yet the Prophet, upon whom be peace, engaged in all the activities that together go to make up what is today called ‘politics’. This includes the organization of men at all levels, collection of taxes or religious dues, regulation of markets, leadership, rulership (hukm), despatch of embassies to foreign rulers, appointment of governors, military training, intelligence gathering, wars and other lesser military expeditions, and so on.

What is more, the Prophet, upon whom be peace, carried out all or most of these activities in Makkah as well as in Madinah. The difference is that in Makkah he did not have a territorial State, while in Madinah he did. This may mean that all aspects of ‘politics’ in Islam are applicable and obligatory with or without a territorial base. Is it the case then that ‘politics’ in Islam are applicable and obligatory with or without a territorial base? And that it is also an obligation (fardh) to seek a territorial base as soon as possible, even if this should involve migration (hijrah)? If so, then an important distinction emerges: politics and political processes are not necessarily related to the State at all times. It is possible that the political processes of Islam, if practiced without a State, inevitably lead to the State. Should this be the case (and the Seerah appears to support this view) then the implications for the Islamic movement are profound.

In this regard perhaps the recent experience of the Shi’i school may be examined, preferably by Shi’i ulama themselves. For many hundreds of years the Shi’i view was that the political processes of Islam, including rulership (hukm), must remain suspended during the absence (ghaibah) of the Twelfth Imam. This position started to be questioned some three hundred years ago, leading to the emergence of marjaiyyat as a form of interim leadership. But this ijtihad reintroduced the political processes of Islam to the Shi’i part of the Ummah, though initially it was in the guise of ‘religious institutions’ and azzadari (grieving for the Prophet’s family) only. But slowly, in stages, this led to the full flowering of the political power of Islam and the establishment of the territorial Islamic State of Iran after the Islamic Revolution. What appears to have happened is that every marja’ was effectively a khalifah ruling over his own ‘non-territorial Islamic State’ consisting of his muqallideen, perhaps comparable to the condition of Muslims in Makkah before the hijrah. It was inevitable, therefore, that sooner or later one marja’ would take the next logical step of setting up a fully-fledged territorial Islamic State. This is what has happened in Iran.

Some sufi shaikhs, calling themselves khulafa, have also run their orders (tariqat) as non-territorial Islamic States. But none has succeeded in establishing an Islamic State on the foundations of sufi orders, though some are known to have opposed tyranny and launched jihad movements. This is an important area for new research. Some of these papers need to take into account the Qur’anic injunctions on rulership, eg, ulul amr, khilafah and vilayah [14].

The term ‘Islamic movement’, or al-harakah al-Islamiyyah, is unknown in the history of Islam and in the literature on Seerah, history, fiqh and usul al-din. It has come into common parlance only recently, especially after the constitutional fall of the Uthmaniyyah khilafah in 1924. Yet it is not difficult to assert that the Seerah itself was the first complete, all-inclusive Islamic movement. If so, the question which arises is: why, for over 1300 years, was the Seerah not viewed as an Islamic movement? The answer to this question may well be that so long as there was an Islamic State in existence and a khalifah in office, the need for an Islamic movement did not arise, or at least was not recognized. After 1924 the ‘Islamic movement’ became the non-territorial Islamic State that filled the vacuum, at least in the Sunni world, caused by the absence of the khilafah. The struggle to re-establish the territorial Islamic State came to be known as the Islamic movement.

The emergence of the Islamic movement inaugurates a new phase in Islamic history. The movements launched by Hasan al-Banna in Egypt in 1928 and by Abul Ala Maududi in India in 1941 can be regarded as the first post-khilafah experiments in bringing together the elements necessary to re-establish the Islamic State. The Islamic movement is now a global phenomenon transcending modern political boundaries imposed by nationalism in the interest of global imperialism. The Islamic Revolution in Iran is a product of a revolution in the theological formulations based on ijtihad within the Shi’i school. But it may be of great value and guidance when it comes to the final stages of overthrowing the established order and creating a new Islamic State in its place. To the extent that the Islamic Revolution also represents a convergence of Shi’i/Sunni political thought in matters of leadership and rulership, it has great value in the study of the Seerah. It is almost certainly the case that divergences within Islam can only converge within the framework of the Seerah. The Seerah is a common ground for all Muslims; it is also the only ground on which all Muslims can stand. The conscious development of the Seerah as the foundation of the global Islamic movement will integrate the movement and clarify common goals across the Ummah. The Seerah as the foundation will also work to remove such tensions as are found today in parts of the Islamic movement over issues such as leadership, stages of growth, and the final goals.

Research in this important area offers great scope for original thought and reformulation of the Seerah for the solution of crucial issues confronting Muslims in all parts of the world today. There are also many definitions of the Islamic movement found in journals and newspapers published by Islamic groups. An attempt to define the Islamic movement in terms of the Seerah should be of great assistance towards its development and the harmonization of its methods and goals. Research in this area might also help us develop assumptions and hypotheses for future organization, priorities, methods and goals of all parts of the Islamic movement. In a sense, the Islamic movement simply means the following of the Seerah in today’s conditions. For this to happen two conditions have to be met: (a) the understanding of the Seerah in such great depth that it can be applied today; and (b) an accurate understanding of the conditions that prevail today. It seems that for a very long time Muslims have not met either of these conditions to any great extent. Those who studied and claimed to have understood the Seerah did not understand the modern world; and those who claimed to understand the modern world did not understand the Seerah. This is a common weakness in all parts of the Islamic movement; hence their frequently far from impressive performances.

Confusion in this area is widespread. The modern nation-States, creations of the colonial powers, also claim to be Islamic States. They have set up an ‘Islamic Secretariat’ and hold an annual conference of ‘Islamic foreign ministers’. Some parts of the Islamic movement take the view that these nation-States can be ‘democratically’ modified in some respects and turned into Islamic States. There is also the view held in some parts of the Islamic movement that all that requires to be done is for an ‘Islamic party’ to win an election and that would convert that country’s government into an ‘Islamic government’. This was the view entertained by Maulana Maududi in Pakistan, and this is still the position of the Tanzim al-Dawli wing of al-Ikhwan al-Muslimoon. What is wrong with this view is that it fails to recognize that a State, any State, founded on the basis of nationalism cannot be converted into an Islamic State without first uprooting nationalism and other colonial influences from its history and foundations. This is now coming to be commonly accepted in all parts of the Muslim world and the Islamic movement. In classical Sunni thought there also appears to have been a willingness to accept a State as ‘Islamic’ so long as its ruler styles himself khalifah. Thus the debate on the issue by-passed the State, and Sunni ‘secondary theology’ concentrated on defining the minimum conditions a ruler must meet before he is entitled to bai’ah. Moreover, these conditions were whittled down to such an extent that any dynastic ruler was more than willing to meet them in order to protect his throne and dynastic rights. The time has come to define the Islamic State in terms of its origin in the Seerah. Once this has been done, khilafah and vilayah as sources of authority and leadership need to be restated in the context of the Islamic State rather than merely as a question of bai’ah on minimal conditions. The explication of historical processes involved in transforming the present political structures into Islamic States is a major challenge facing Muslim intellectuals working in the Islamic movement framework.

This is an important area that offers particular challenges. There were no fewer than 68 military campaigns launched by the Prophet, upon whom be peace, from Madinah. These included a number of raids to harass the trading caravans of Quraish of Makkah that led to the Battle of Badr in only the second year of the hijrah. Another empire builder, ruler or adventurer in a similar position might have sought some years of peace in Madinah for the consolidation of his power before taking on his adversaries. The Prophet did precisely the opposite. He chose an early confrontation in the battlefield between his handful of followers and the extensive might of Quraish of Makkah and their allies. He clearly realized that an early victory over Makkah was essential for the consolidation of his power even in Madinah. To provoke the Makkans at that time was clearly an act of faith, not of reason. We need to put all of the military campaigns in a similar context. What were the underlying goals the Prophet pursued through his military campaigns? Why did he launch so many military campaigns in such short a time?

Today all mankind is in the grip of a single civilization, its power, values, culture and economy. This dominant civilization is the Western civilization, while the civilization of Islam now exists only as a dismembered sub-culture in various forms in different parts of the world. Islam no longer has a civilization that can claim to have global power or a working economic system, though it still has strong values that are global, and also retains a global cultural and political identity. It is this global political presence that the West is now trying to brand as ‘fundamentalist’ and ‘terrorist’. Can we justifiably compare the West with the Quraish and its civilization with jahiliyyah? It is now universally accepted among Muslims that the West is determined to eradicate all remaining traces of Islam from the world. Having established its political and economic hegemony over most parts of the world, the West is determined to make sure that its power can never be challenged by Islam again. The West views Islam as the only possible source of challenge to its domination. This challenge does indeed exist in the form of a widespread realization among Muslims everywhere that they have to escape from the stranglehold the West has acquired over them and over Islam. At one level, it is a question of generating Islamic Revolutions in all Muslim countries to escape from the West’s manipulation and control. But this is not enough. We have to go on to create, or recreate, a new civilization of Islam that offers mankind peace, security, moral upliftment, and economic and social justice (‘adl). The Seerah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace, is clearly the soil in which the roots of this new civilization exist. These roots have to be found, defined and developed. Ultimately the struggle between Islam and the West will not be decided by bombs and technology; this war will be decided by the emergence of a superior civilization in which mankind is assured of security, physical and moral health, and, above all, justice. The foundations of the Western civilization are based on oppression, aggression, enslave-ment, exploitation, brutality, war, genocide, immorality, inequality and injustice. The true face of the West has to be exposed to all mankind, including people in the West itself. And, simultaneously, an alternative civilization of Islam has to be shaped from the Seerah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace. This also offers new challenges in the form of research methodologies that shall have to be applied to the study of the Seerah. This clearly is a rich area for original, even speculative, research.

The Seerah of the Prophet of Islam, upon whom be peace, is a vast ocean which cannot be charted in a short paper. Any attempt to do so would be futile. The object of this paper has been to indicate, as briefly as possible, some of the issues that need to be addressed. Ulama, scholars, intellectuals, students and writers will need to focus on one or more of these areas and build on them according to their own preferences. Once work in this direction is started, fresh ideas and approaches to the understanding of the Seerah, and new issues for debate on the subject of the Seerah, will continue to emerge for many, many years to come. Such an intellectual revolution, pulling the Ummah together on the common ground of the Seerah, is an essential pre-requisite for the future success of the global Islamic movement. Only then can the Ummah be lifted out of its present state of neo-jahiliyyah, and the foundations laid for a new era of Islamic civilization in the future.

1. See also Al-Qur’an, 62:2-3; 21:107; 7:158.

2. “uswatun hasana”, Al-Qur’an, 33:21.

3. Al-Qur’an, 95:4.

4. Al-Qur’an, 22:39.

5. Al-Qur’an, 28:83, 38:26.

6. See also Al-Qur’an, 5:44-49, 4:65.

7. Malukiyyah is defined in the Qur’an in answer to the Prophet Ibrahim’s (pbuh) request that his children too should inherit leadership. Allah replied: ‘But my Promise is not within the reach of evil-doers’ (2:124). Here the message is that being the progeny is not enough. The successor must also be muttaqi. The Qur’an also defines malukiyyah as an unjust system in which the ruler is succeeded by a member of his family.

8. Al-Qur’an, 25:31.

9. On this issue, see Sayyid Qutb, Milestones, first published in Arabic in 1964, especially the chapter on ‘Jihad in the cause of Allah’.

10. Al-Qur’an, 28:83.

11. Al-Qur’an, 33:40.

12. Al-Qur’an, 3:159, 9:128, 15:88.

13. Al-Qur’an, 48:29.

14. Al-Qur’an, 38:26.

Dr Kalim Siddiqui (1931-1996) was Director of the Muslim Institute, London, and one of the leading thinkers of the global Islamic movement. His commitment was to helping generate an ‘intellectual revolution’ in Islamic social and political thought, which could lay the foundations for a future Islamic civilization and world order.

The Seerah of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) was a lasting influence on Dr Siddiqui’s ideas and work. Many of the key areas on which he wrote — Muslim political thought, the use of power, the unity of the Ummah, the concept of leadership in Islam, the nature of the Islamic state — were based on his reading of the Seerah. He also regarded the Seerah as the common ground on which all Muslims, of all schools of thought, could stand together to work for the good of the Ummah as a whole and the establishment of a new Islamic civilization and world order.

Above all, Dr Siddiqui believed that studying the Seerah from ‘a power perspective’ was the key to an intellectual revolution in Muslim thought. At the time of his death, he was planning to launch an international research project into the Seerah as his next major work. This paper, on which he was still working at the time of his death, outlines some of the areas in which he believed Islamic movement intellectuals must work. It was first published by the ICIT in 1998.