Eric Walberg

Eric WalbergWhatever the West touches, it destroys. Somalia, Sudan and Ethiopia show the evidence of Western meddling and aggression.

In 2016, Somalia was declared the most fragile state in the world — worse off than Syria. Famine struck yet again in 2017, compounded by President Donald Trump’s attempt to ban Somalis from entering the US. But for the first time since 1991, when Somalia collapsed along with its one-time ally the Soviet Union, Somalia now has functioning political institutions.

Dual US-Somali citizen Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo became president in February 2017, approved by the US; refugees are returning from the US, Canada, and Europe, and remittances from them buttress the economy. Just to make sure Farmajo knows who is really in charge, Trump ordered an air strike on suspected militant bases on April 22, 2017, near the Bab al-Mandab strait chokepoint separating Yemen from Eritrea, boasting it killed 150 Shabab fighters.

The 1980s were a monstrous decade. We are still living out the disasters that the Cold War and the US war to prevent “the advance of socialism” spawned, which had been on the books since the end of WWII, and was reaching its logical conclusion by then. After two world wars, everyone expected peace, and the vast majority, socialism. No such luck. Hundreds of coups in the 1950s and 1960s orchestrated by the CIA kept most countries toeing the imperial line. But after Vietnam, for a few shining moments in the 1970s, there was a shift by a slightly sobered America.

The world breathed a sigh of relief. Somalia was prospering, free of British shackles, not yet embraced by the US. Ethiopia had a Nasir-like military coup in 1974 promising socialism next door. Sudan was at peace and pursuing a Nasirist policy under Colonel Ja‘far Nimayri. But the region was beginning its “time of troubles,” soon experiencing the fallout of its century of imperialism with a vengeance.

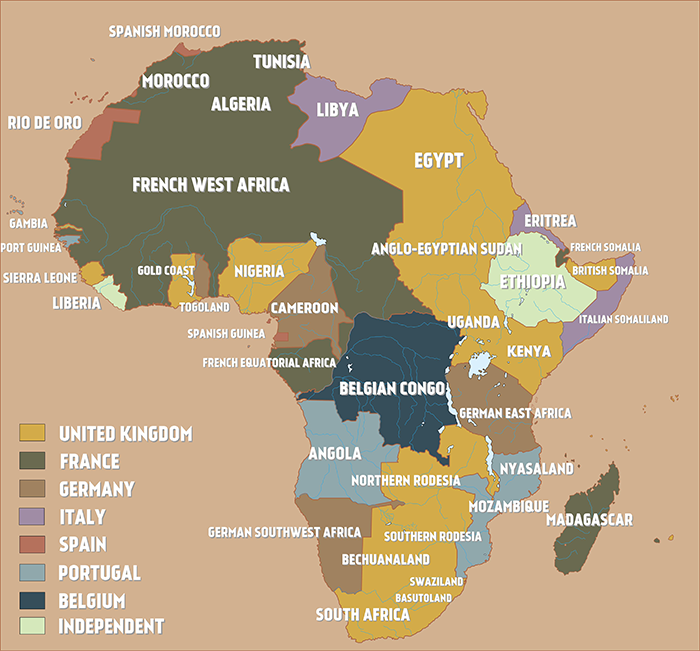

Somalia, a country of 12.3 million, has one of the most illustrious histories among Muslim states, prosperous for thousands of years as a trading nation perched on the strategic Horn of Africa, an early convert to Islam. As with all of Africa, it went into sharp decline in the late-19th century, after the Berlin conference of 1884, when European powers began the “Scramble for Africa.”

In the last heroic resistance to imperialism, the Dervish leader Muhammad ‘Abdullah Hasan rallied support from across the Horn of Africa and began one of the longest colonial resistance wars. Hasan emphasized that the British “…have destroyed our religion and made our children their children” and that the Christian Ethiopians in league with the British were bent upon plundering the political and religious freedom of the Somali nation. While all other Muslim states fell to Christian invaders, Somalia held out.

Hasan acquired weapons from the Ottomans and Sudan. But the Ottoman Sultanate collapsed, and British War Secretary Winston Churchill was free to use the new airplanes in 1920 to bomb the “mad mullah” and Somali forces, just as he was doing in Iraq. It took four invasion attempts before Hasan’s Dervish state was defeated, and territories turned into a British “protectorate.” The Italians moved in on the British in the 1930s, taking over northern Somalia to join Ethiopia in their short-lived colonial empire.

The 1920s and 1930s were a busy time for Britain in the Muslim world. Somalia was every bit as strategic as Palestine, and British schemes for both proved to be time bombs that still are plagued by and plague the West. Britain ceded most of the present territory of Somalia to Mussolini in 1925 as a reward for the Italians having joined the Allies in WWI. The British retained control of the southern half of the partitioned Jubaland territory, which was later called the Northern Frontier District, and the northwestern province Somaliland, which declared independence in 1991, and is now a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. Italy administered central Somalia after WWII, until independence in 1960. French Somaliland (Djibouti) stayed with France till 1977, just too convenient strategically to give up, and is now the headquarters of the US AFRICOM regional military command.

Italy proved to be the most helpful of the lot to Somalis, providing education and otherwise preparing Somalis for independence, and the Italians are now remembered more or less fondly. Italian was the lingua franca till the 1970s, there being no Somali alphabet and the population illiterate till independence. The British did nothing, and created the conditions for endless regional war by giving the predominantly Somali Muslim Ogaden plateau to (largely Christian) Ethiopia, and another Somali territory to (largely Christian) Kenya. At the same time, of course, it was preparing to bequeath Muslim Palestine to (European) Jews.

In all three cases, Muslims were treated as second rate, of no use to the imperialists, as they would never abandon Islam and join in imperial schemes. The British set the stage for Somalia to fail without colonial “guidance.” To be fair, Britain (and France) were just doing what the new masters, the US, demanded in the 1950s, shaping up Africa to meet its own needs, so the blame must be shared today.

Given its handicaps, Somali independence was bittersweet. After a halting start, a military coup put Siad Barre (1910–1995) in the presidency from 1969–1991. Like Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, Kwame Nkruma in Ghana, and Jamal ‘Abd al-Nasir in Egypt, Barre took the Soviet Union and socialism as the template for development. Volunteer labour harvested and planted crops, and built roads, hospitals, and universities. Almost all industry, banks, and businesses were nationalized, and cooperative farms were set up. A new writing system for the Somali language was also adopted, and Somali replaced Italian as the language of the public sphere.

Although his government forbade clanism and stressed loyalty to the central authorities, Barre’s dictatorship became a hostage to his own clans. Even so, it was popular, presiding over a vibrant economy and stabilized by egalitarian economic policies. Portraits of him in the company of Marx and Lenin lined the streets on public occasions, though he did not promote a personality cult. He advocated a form of scientific socialism based on the Qur’an and Marx, emphasizing Somalia’s traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League in 1974.

That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union (AU). The mid-1970s were halcyon days for Somalia. Barre was the Soviet Union’s poster child, not so willful, it seemed, as Egypt’s Nasir, and not (yet) toppled like Lumumba and Nkrumah.

But storm clouds were on the horizon. In the late-1970s, buoyed by Somalia’s success, fed up with a corrupt (Christian) government under the aging Emperor Haile Selassie, and inspired by the Ethiopian revolution, the Western Somali Liberation Front in Ogaden, began a campaign for union with Somalia. Rebels wanted Islam and socialism, emulating liberation movements throughout the colonial world. Their plea for help was heard, and in July 1977, the Somali army marched into the Ogaden, capturing most of the territory, welcomed by the native Somalis, but attracting the ire of the entire international community.

This was at the height of detente, and the Soviet Union was playing more-or-less by the implicit rules of detente — don’t provoke revolution or civil war, but help friendly regimes. “Socialist countries shouldn’t invade other socialist countries — just get along,” was the Soviet philosophy. Unfortunately for the Soviets, these regimes don’t play by international rules, and Somalia’s Barre was shunned by the Soviets, giving preference to Ethiopia’s Mengistu Haile Mariam.

The invasion was reversed, and the US decided not to join the Soviet Union in condemning the violation of international law, but take advantage of the falling out of the “enemy,” and cultivate Barre as a useful ally. Only a year later, much the same scenario would play itself out in Afghanistan, where the US chose to side with the mujahidin against the Soviets, with the tragic results we still suffer from today.

Barre expelled all Soviet advisers and switched allegiance to the West, with China his only socialist ally. This tragedy was a windfall for the US, which supported Barre despite his socialism and invasion of the Ogaden, but as usual, US aid was the kiss of death. After 21 years, Barre’s Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party was eventually forced from power in 1991, Somalia the latest failed state. Barre died in political exile in Nigeria in 1995.

Barre’s Ethiopian nemesis, Mengistu Haile Miriam, was also ousted in 1991, both victims of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Ronald Reagan had won the Cold War, Ethiopia had kept the restless Ogaden, Somalia was a mess, the imperialists had a firm hold on Djibouti. Both Somalia and Ethiopia had even sorrier fates ahead of them as famine nations.

They should have abided by detente rules, and initially did. But “great game” rules clicked in. Though Barre was a pariah, he became “our pariah” by 1980, along with the Afghan mujahidin. Instead of working with the Soviets in Africa (pushing Barre out of his “greater Somalia”) and in Central Asia, the US under Ronald Reagan launched old-fashioned war and subversion of anything that was socialist, leaving only rubble and terror in Somalia, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan, which continues to plague the world.

It also created massive refugee populations from all three countries. These were not intended, and have been a headache for the West ever since, but are the silver lining in the US strategy. They have brought millions of Muslims to the West, undermining the supposed “Judeo-Christian” civilization, which is really only just imperialism dressed up in pseudo-religious morality sound-bytes. These Muslims are forcing the West to deal with Islam, now an integral part of Western society.

The diaspora, one of the largest, spread from Sweden to the US, and Somalis abroad are forced to downplay the clan system, though it still exists where enough of one clan can form a community. But the second generation exiles are not interested. Andrew Harding, author of The Mayor of Mogadishu: A story of chaos and redemption in the ruins of Somalia (2016), was told by an interviewee that Somalis are adaptable, almost like a new set of clans. The American Somalis are “a bit more outgoing, they like to push things harder.” The Scandinavian Somalis are the opposite, “endlessly trying to bring everyone on board.” The British are somewhere in between.

They are also remitting billions of dollars to relatives in the devastated countries, doing far more good than bureaucratic official aid, much of which is embezzled and otherwise used as the West sees fit, rather than as the locals would like and need. This in turn is pushing westerners who really, really want to help, to restructure aid programs to meet local needs (microloans, cell phone banking, hands-on local infrastructure using traditional techniques tweaked by modern technology, just giving a “basic income” to penniless peasants).

Imperialism is greedy, cruel, selfish, but all people living under the system are not, and this “peoples diplomacy” is slowly gaining momentum. The jury is still out on the final outcome of the imperial saga. The dreams of socialism are more or less dashed, but for Somalis and some Afghans old enough to remember, their days of socialism in the 1970s are fond memories, before the lure of empire (Somalia) and secularism (Afghanistan) took over, “masterfully” manipulated by the US.

The US “beat” the Soviets in the 1980s in Africa and Central Asia, but it is hard to see any evidence of victory three decades later. Whatever advances have been made are more in spite of the US, or by emigres remitting their US dollars to relatives, at least in Somalia. In Afghanistan, there really is nothing to show that will last. The 16 years of occupation after two decades of US inflicted war have left a devastated, fractured country, with a shallow veneer of western urban chaos, which only gets worse. At least the Somalis kept the US from occupying them. The US-sponsored Ethiopian proxies retreated after two years in 2009, driven out by Somalia’s Taliban, the Shabab.

The African Union (Ugandan, Kenyan) troops sent in to stabilize things in the 2000s marked a new African solution to African problems, but Africa is too weak and disorganized to make this more than a hopeful sign.

We barely mentioned Sudan, which flirted with socialism in the 1970s, but sided more-or-less with the US. It has escaped invasion and failed-state status, but ended up, like Somalia and Ethiopia (and Afghanistan), divided and with ongoing rebellions, with nothing positive resulting from the brutal wars of secession and US sympathy, and no end in sight.