Jacob Knight

Jacob Knight The 15th General Election in Malaysia, held on November 19, marked a major turning point in the political history of the Southeast-Asian kingdom. In a country that had for over 60 years been ruled by the same political coalition known as Barisan Nasional (National Front, known as the Alliance Party until 1973) since independence in 1957 until the elections of 2018, the past five years have seen probably the biggest political upset in its history. In order to understand why the latest election was such a major shift in the country’s political history, we must first take a look at the unique demographic and political makeup of Malaysia.

Almost from the very beginning, there has been a clear ethnic divide in Malaysia electoral patterns. Whereas the Malay population and the indigenous tribes that together constitute 68.8% of the population under the term Bumiputera (children of the soil), generally voted for more conservative-minded Malay-dominated parties like Barisan Nasional or the Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (Malaysian Islamic Party, abbreviated as PAS), the significant Chinese minority of about 23% often tended to favour liberal and more free-market oriented parties such as the Democratic Action Party (DAP).

As fears of ethnic Chinese political and economic domination arose among the Malay community and its political leadership during the march towards independence, the system of Bumiputera status was enacted to ensure the “special position of the Malays and natives of any of the States of Sabah and Sarawak and the legitimate interests of other communities” according to Article 153 of the country’s constitution.

This was further expanded in the 1971 New Economic Policy, and ensured certain innate benefits for Bumiputera citizens in matters such as scholarship grants, civil service positions, real estate purchase and business subsidies. Combined with the higher birth rate of Malays in general and a certain degree of out-migration of Chinese Malaysians has resulted in a situation where the Bumiputera percentage of the population has increased from just over 50% in 1957 to almost 70% today.

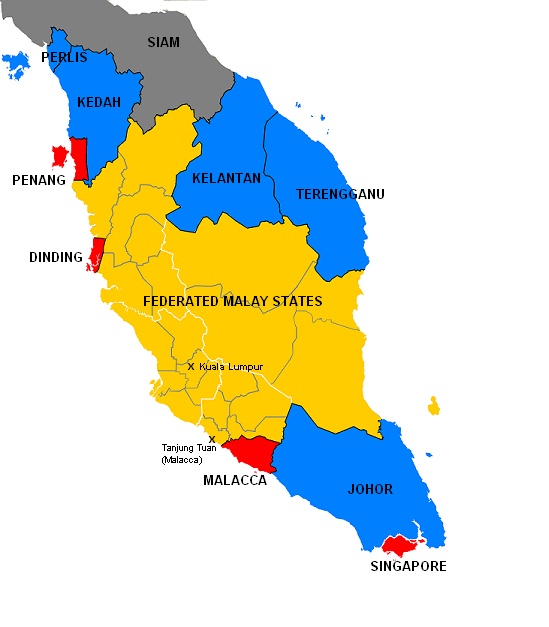

This division also expressed itself on a geographical level, often tied in with the British colonial history of Malaysia. Since the Chinese migration wave into the colony then known as Malaya had been centered around urban and financial centers, particularly the crown colony known as the Straits Settlements and made up out of areas such as Singapore, Malacca and Penang, these regions became the hotbed of DAP activity. The division even resulted in the independence of Singapore, an act of peaceful secession that followed the 1963 race riots and was seen by both sides as a way to reduce tension within Malaysia proper.

Much of the central part of peninsular Malaya was united under the so-called Federated Malay States, whereas the northern and southern edges were collectively called the Unfederated Malay States and as such were not in fact governed by one single colonial administration. The situation on the island of Borneo was arguably even more complex, with the present state of Sabah being the protectorate of North Borneo, while the Raj of Sarawak was an internationally recognised independent country under a dynasty of British-descent monarchs commonly known as White Rajas.

This unique diversity in history has resulted in a situation where historically Islamic movements like PAS stood strongest in former Unfederated areas, and the historical Federated lands being the stronghold of Barisan Nasional. Sabah and Sarawak have usually voted for their own parties that above all desire a maximum degree of autonomy for their respective states, and are generally open to collaborate with whomever can guarantee this. The result was that the balance of power in Malaysia swung towards Barisan Nasional for the first 61 years of Malaysia’s existence as an independent state.

Under BN, a sort of catch-all party mostly leaning towards social conservatism, economic liberalism and Malay nationalism, Malaysia has known a relatively stable political system, which however proved to be susceptible to corruption, graft and cronyism. While elections were held in typical liberal-style democracy, there seemed little indication until recently that the power monopoly of Barisan Nasional would ever be broken, with some arguing that things like extensive gerrymandering, the use of public funds for political campaigns, and so-called “phantom voters” contributed to the continuing success of the ruling coalition.

Every single Prime Minister of Malaysia prior to 2018, no matter how different their personal political directions compared to one another, were members of Barisan Nasional. And even when 2018 saw the first ever victory of an opposition party, it was led by former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed, then 92 years old and erstwhile BN member.

Leading a coalition of liberals and reformists known as Pakatan Harapan, Mahathir’s new stint in power came to an ignominious end less than two years later, when internal political turmoil forced the government to resign. When the succeeding government had to resign as well just 17 months later, this led once again to Barisan Nasional taking over power under the leadership of Ismail Sabri Yaakob. The unrest and instability did not end here, however, and Sabri was eventually forced to call early elections, that resulted in the upset of the 15th General Election on November 19.

While it was generally expected that the elections would be a significant challenge to BN and likely create a situation in which no party would manage to achieve absolute majority in parliament, and while the continued success of the Pakatan Harapan coalition among the urban and more liberal centers of Malaysia was also not a surprise, the major upset in the recent election came from a completely different side: the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS).

PAS has a complex and fascinating history, combining elements of pan-Islamism with Malay nationalism, socialism and general anti-colonialism. Founded in 1951 as the Malayan Islamic Association, the movement experienced remarkable growth under the leadership of Burhanuddin al-Helmy, who took over the reins in 1956. Al-Helmy, known to British colonial authorities as a “radical nationalist and Islamic thinker”, was notable for his support of left-wing economic policies in the line of Indonesia’s president Sukarno, as well as for his uncompromising dedication to anti-colonialism and the preservation of both Malay culture and the Islamic identity of his fatherland.

The particular political identity of Burhanuddin al-Helmy was perhaps best expressed by the names of the two earlier parties he had fulfilled leading roles in: the Malay Nationalist Party and the Hizbul Muslimin. Two parties that, incidentally, faced heavy-handed crackdown at the hands of the British colonialists from the day they were formed. Steering PAS into building up a power base in the rural and generally poorer areas of Malaysia and focusing on both the country’s Islamic identity and social policies to benefit the lower classes, al-Helmy managed to win 13 seats in the 104-seat parliament in 1959. PAS also took control of assemblies in the northern states of Kelantan and Terengganu.

However, times were not always kind to PAS. Following crackdowns that saw Burhanuddin al-Helmy imprisoned on charges of conspiring with Indonesia, and a long illness afflicting him after his release until his death in 1969, PAS was steadily drawn into the catch-all unity message that the national government dominated by BN precursor the Alliance Party proclaimed. This policy proved to be disastrous, as the voter base of PAS overwhelmingly rejected this move towards the “mainstream” and wiped out much of the party’s electoral gains during the 1970s.

This, combined with the worldwide shockwave that was the Islamic Revolution in Iran of 1979, led to the rise of a new generation of Islamic thinkers and activists within PAS, most of them educated religious scholars that were collectively called the “Ulama faction” within the party. By 1983, this ulama group had risen to the leadership of the Malaysian Islamic Party, broke away from BN and the Malay nationalist focus and rebranded the party along heavily religious lines that drew clear inspiration from the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

The revival of the party was greatly hindered by the ensuing conflict with the central government in Kuala Lumpur, however, with the so-called Operation Lalang resulting in the arrest of 15 leading PAS politicians and 14 of its members even being killed in a police raid known as the Memali Incident of 1985.

Persisting in its ideals and goals, PAS experienced major revival in the 1990s, retaking control over the northern states of Terengganu and Kelantan and steadily building up its powerbase to the point where they managed to win almost 17% of the popular vote and 18 parliamentary seats in the famous elections of 2018 in which BN lost for the first time ever. Remaining in firm opposition to the Pakatan Harapan coalition of Mahathir Mohamed and its liberal-leaning agenda, PAS played a key role in the 2020 collapse of the Mahathir government by allying with disaffected traditionalists and Malay nationalists to found the Perikatan Nasional (National Alliance or PN), and even managed to obtain a few ministerial positions in the short-lived government of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin.

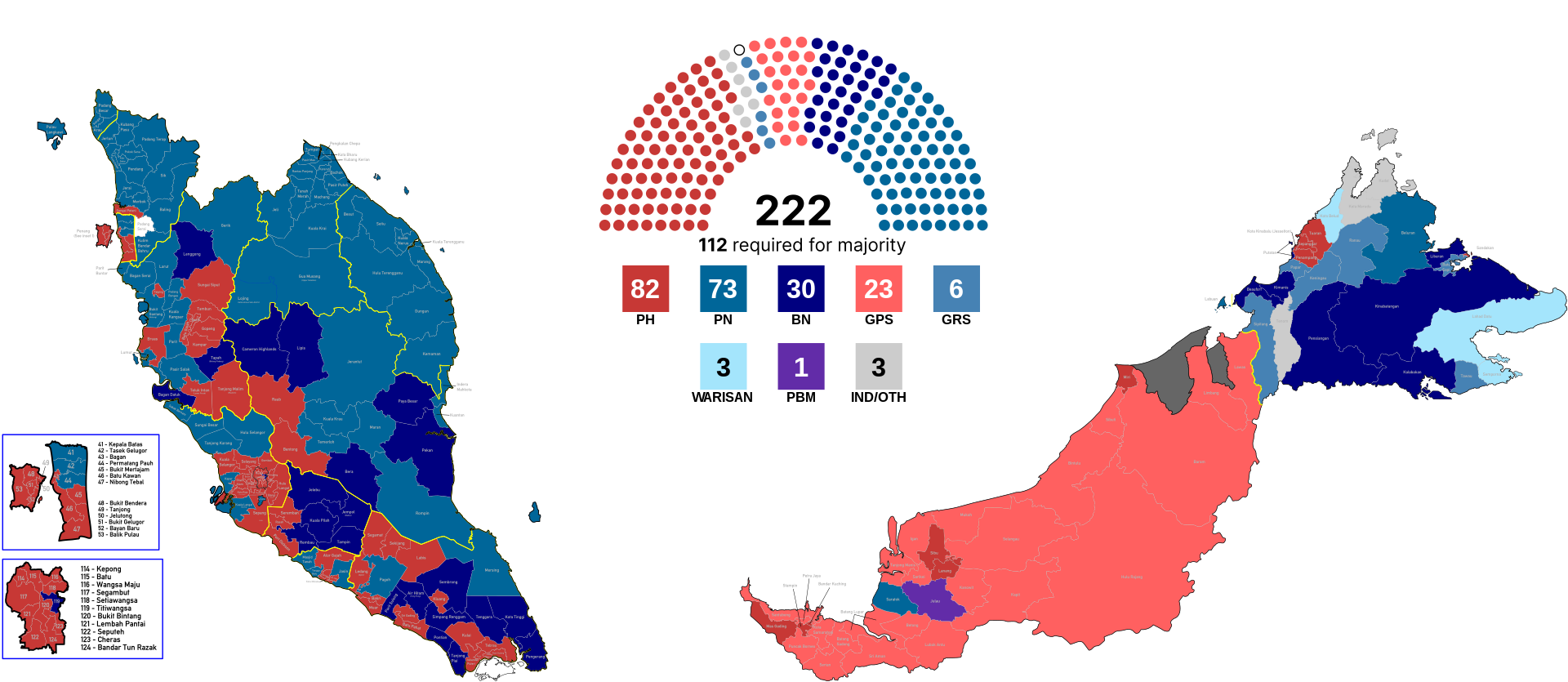

Despite this steady rise in position PAS has experienced in recent years, few would have predicted the major electoral victory that November 2022 would bring for the Islamic movement. While the various parties of the Malaysian political landscape contested the elections under their respective alliances in the campaigns, seat division of the Malaysian parliament, the Dewan Rakyat, happens according to the percentages gained by their member organizations. As such, while the election was technically won by the Pakatan Harapan coalition under Anwar Ibrahim, who has now been appointed prime minister, the breakdown in parliamentary seats tells a very interesting story.

When moving beyond the mere blanket terms of political coalitions such as Pakatan Harapan, Perikatan Nasional and Berisan Nasional,we see that the single biggest party in Malaysia’s parliament is PAS, the Malaysian Islamic Party. A major jump forward for a party that barely managed to ensure its continued existence just over 30 years ago. With a total of 49 seats in the 222-seat parliament, PAS far outpaced its old rival BN, which even as a coalition of four smaller parties only managed to win 30.

The only party that came anywhere close to the Islamic Party’s score is the Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party, which is a member of Anwar Ibrahim’s government coalition with 40 seats. When we consider that PAS remains in a comfortable alliance with the Malaysian United Indigenous Party (Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia or PPBM), which won a further 30 seats of its own, we can see a united Malay-Islamic opposition front of 73 seats.

This revelation was not lost on media worldwide, and the unexpected success of PAS was reported by channels from China to the United States. Malaysian news outlet Free Malaysia Today even called the results a “Green Wave”. Journalists correctly pointed out the fact that Anwar Ibrahim is likely to have a tough opponent in PAS and the Perikatan Nasional coalition that it de facto leads. The formation of a government coalition was not without its own issues, and it was only after a meeting of the Sultans of Malaysia that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (as the king of Malaysia is officially called) appointed Anwar Ibrahim as prime minister with a call to all parties to join a major unity government. The Perikatan Nasional coalition flat-out refused, opting instead to remain a firm opposition bloc.

Analysts have also pointed out that the demographic-electoral split in the country seems to have only grown wider, now that the catch-all Barisan Nasional has been wiped from power. A quick comparison between the ethno-religious map, bearing in mind that the Malay population is overwhelmingly Islamic, the indigenous population of East Malaysia primarily Christian and the majority of Chinese Malaysians Buddhist, shows that the electoral results are still heavily influenced by ethnic consideration of voters. On Peninsular Malaysia, the PAS-dominated Perikatan Nasional (PN) has made inroads in all major Malay-dominated areas and states, while Pakatan Harapan retains a strong position in urban centers such as the island of Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca and the border with Singapore.

The political future of Malaysia remains unclear, but it is certain that Parti Islam Se-Malaysia is planning to wage a coordinated opposition effort against the Anwar Ibrahim administration. With a historically high electoral score, sure to be considered proof of the efficiency of PAS strategy of rallying the common Malays in the countryside in particular, PAS and its allies in Perikatan Nasional are sure to step up to the challenge. They quite have come too far and have been through too much to give up on the struggle now.

(Jacob Knight is a historian.)