Eric Walberg

Eric Walberg

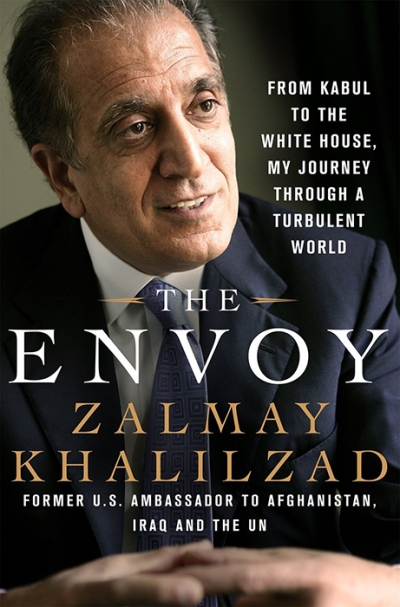

The Envoy: from Kabul to the White House, My Journey through a Turbulent World by Zalmay Khalilzad; Pub: St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2016, 336 pages. Price: $11.60 Hbk.

The Afghan-born Zalmay Khalilzad is the lead US negotiator in talks with the Taliban. In short, he wants to end the 18-year-long war but maintain US influence and dominance in the landlocked country. To their credit, the Taliban have not fallen into the trap of accepting a ceasefire, as proposed by Khalilzad; for them a ceasefire is off the table until the complete withdrawal of all US troops. If there is one lesson the Taliban have internalized after 40 years of fighting, it is that they have forced their enemies to withdraw only because they are prepared to fight. That is why the Americans have been forced to the negotiating table; not because they like the Taliban’s dress or Afghan kebab! To understand how Khalilzad operates and where his loyalties lie, we publish this review of his autobiography, The Envoy. It offers useful insights into his mindset.

The art of autobiography is a slippery one, “a review of a life from a particular moment in time.”1 Whatever truths Zalmay Khalilzad has revealed in his 2016 autobiography are by definition personal truths, confessions, with lots of caveats.

The Afghan version of Horatio Alger’s Ragged Dick, Khalilzad began life in a remote village, riding a horse to school. He brags of winning a race by taking a short cut through a farmer’s melon field, crushing the precious fruit but bragging to mommy upon reaching home. No remorse for collateral damage. No punishment. He would go on to repeat his success as ambassador and hitman in first Afghanistan, then Iraq, then Afghanistan, then the UN.

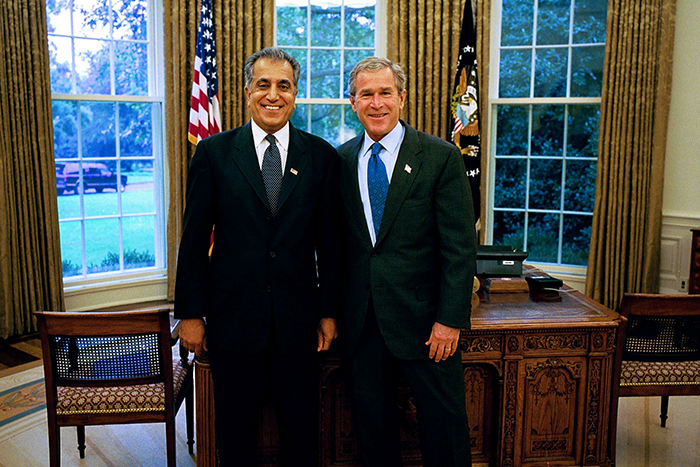

He is a staunch Republican, so he disappeared into private consultancyl and during the Barack Obama presidency. He became president of Khalilzad Associates. In September 2018 he was rehabilitated, hired by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to serve as special envoy to Afghanistan. Good timing with the autobio, Zal.

Lots of treacle and lots of holes, but there are enough surprises to keep one reading to the end. First surprise: as a child, he remembers “our family followed the conflicts between India and Pakistan. We rooted for New Delhi, not so much because we loved India but because Pakistan was our principal adversary.”

Afghans feel that the British cheated them by first stealing and then giving away Pashtunistan to the newly-created Pakistan in 1947. Khalilzad pines for greater Afghanistan, which would include Turkmenistan to the north and that big, wild chunk of Pakistan to the south. That grudge is an important reason that Afghanistan eventually unraveled after 1973, when the king’s cousin Sardar Mohammed Daoud staged a coup and rattled his sabre at foe Pakistan. The Pakistan government decided to retaliate by supporting Afghan Islamists, including future mujahidin leaders Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Burhanuddin Rabbani, among others.

Daoud turned to a US eager to stop more Soviet “victories” in the still hot Cold War. This prompted the Afghan communists to overthrow Daoud. He should have read his recent history: US promises are seldom kept. Just ask those Hungarians who survived their 1956 debacle. The Soviets, on the other hand, stand by their comrades, even if it means disaster.

Khalilzad is a chameleon, ever adapting to circumstances (except for his love of America and his animosity to Pakistan and commies). He began his love affair with America when he was chosen as one of 30 Afghan students to live and study for a year in the US (California) at the age of 15 in 1966. It was love at first sight (Afghan President Ashraf Ghani also went and the two became lifelong friends).

His summer job was vaccinating chicks and cleaning chicken coops, which he loathed. This was lower class work in Afghanistan. But he had an epiphany, “Here, any and all work was seen as a valuable social contribution.” Tell that to the despised Mexican illegals just down the road in California’s Central Valley.

He refused money for picking nuts in his hosts’ almond orchard, but then learned that the American practice was for children to accept allowances, to learn the “value” of work. How about: an objective truth of capitalism is the centrality of the cash nexus. That requires indoctrinating children in the belief that money governs all relations, including family relations, the foundation of America’s “flawed democracy.”2

He returned to Kabul and first studied medicine, as his parents wanted. But America had fallen in love with Khalilzad too, and he was soon in Beirut at the American University, where he met his future American wife Cheryl Benard. Like all his fellow students in the heady 1970s (and Afghan communists plotting to take power), he sympathized with the Palestinians. His colours changed, as befits a chameleon.

That was Khalilzad’s (short-lived) flower child period. He went on to the University of Chicago, where he studied under Albert Wohlstetter, a prominent nuclear deterrence thinker and strategist (his moment of fame, the 1958 Foreign Affairs “Delicate Balance of Terror,” or “peace through MAD strength”). Wohlstetter provided Khalilzad with contacts within the government and RAND corporation, both of which became Zal and Cheryl’s home.

Despite his flirtation with Palestinian radicalism, Khalilzad was never lured by socialism, and was happy to join in its destruction. US soft power is so alluring to naive youth in the Afghanistans of the world. He was the right guy in the right place at the right time. At the tender age of 34, Khalilzad was suddenly senior State Department adviser on the Soviet-Afghan War.

But he came away from talks with the Afghan mujahideen in the 1980s worried that they wanted a unified Islamic caliphate rather than a nation-state. Instead of communism, they wanted, not capitalism, but Islam! This was also General Zia’s vision of a united confederation of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia, funded by the Saudis against his beloved India (that is believed to be the reason why the CIA killed Zia in the August 1988 plane crash, sacrificing ambassador Arnold Raphel in the process. General Zia had grabbed Raphel’s hand after the tank exercises in Bahawalpur to fly with him. Zia had hoped the Americans would not kill him if the US ambassador were with him! – Editor).

The mujahidin’s ultimate objective should have set off alarm bells, but Khalilzad’s distaste for the commies blinded him, and, despite his distaste for both Pakistani ruler Zia and Islam, he encouraged arming Zia with F-16s (they arrived in 1983) in exchange for facilitating American aid to the Afghan resistance. Bad move in retrospect? No confession here.

America would see the Afghans through, he was sure. And when he was catapulted to ambassador of Afghanistan in 2003, he made “America love” his theme song. He thinks it worked. As proof, he recounts how he arranged a visit by Northern Alliance leader Mohammad Fahim, who returned to Kabul ecstatic, “In the US everyone lives in a large villa. We don’t have anything that they want. I am convinced that the Americans are here to help us.”

In 1979, Khalilzad wrote an anonymous article in Orbis arguing that Afghans were likely to rise up against the new Communist government and that the Soviet Union might intervene militarily. In December, he got a call from Zbigniew Brzezinski’s office who was serving as Jimmy Carter’s national security advisor, and was told he had been “outed” and the White House wanted him.

The US was already funneling money to Islamists in Kabul, provoking what Khalilzad predicted might happen. Mr. Cameleon was happy to target the Soviet Union. He confesses, “I might as well own up and help out with US policy. I told him [Brzezinski’s assistant] I couldn’t go public due to my family in Afghanistan.” Blackmail or plain old secret agent?

Khalilzad has one endearing feature. Even as US relations with Iran careen from love to hate to dislike to “really hate,” he is remarkably immune to this passionate discord. He recalls that the British withdrawal from the Gulf in 1971 created a vacuum that Iran’s Shah tried to fill, but Iranian students at AUB would have none of it. They were (like all students, even Khalilzad) anti-Shah and pro-Palestine. The Shah’s love affair with US-Israel in those radical 1970s was like a trigger for their wrath. He was fascinated with them and the charismatic Imam Khomeini, then exiled in Paris.

Here Khalilzad’s inner Horatio Alger kicked in. Why not go to Paris and meet the legendary Imam? It worked. He was granted an audience. The Imam didn’t realize Khalilzad spoke Persian, and told his translator, “Tell the American professor that we want democracy and rights for women. This is what these Americans like to hear.” I wasn’t there, so I am taking Khalilzad’s word for this, but it is hardly damning.

The Afghan-American was impressed when Imam Khomeini referred to Plato’s Republic as a model. Clerics would formulate the moral agenda of the state, he was told, while technocrats would provide the administrative skills. Khalilzad came away impressed, and, though there’s no confession here, he clearly supported his Iranian student friends in their efforts to overthrow the Shah.

He admits (admires) that Iran was the main supporter of the Northern Alliance throughout the 1990s. At the November 2001 UN conference in Bonn to form the transitional government, Khalilzad was impressed by Iranian ambassador to the Northern Alliance Muhammad Ibrahim Taherian’s knowledge about Afghanistan.

The Iranian ambassador knew the last communist leader Najibullah well, and told Khalilzad that it was Pakistani officers who shot the leader before his body was hung from a pole on the streets of Kabul. Khalilzad supported (supports?) negotiations with Iran as part of a larger effort to secure regional support for the post-Taliban government.

Khalilzad’s “finest hour” was surely in 1988, when the UN-sponsored proposal to end the carnage in Afghanistan was about to be signed by Ronald Reagan. The US (State Department and CIA) would agree to recognize the communist regime as soon as the Soviet withdrawal began, and to cease the flow of arms to Pakistan and on to the rebels.

Already, the US was getting cold feet on the mujahidin and would be able to put a lid on them before they got out of hand. Khalilzad thought the deal was far too favorable to the Soviets. The State Department and CIA were in favor, as they gambled the Soviets would never actually withdraw, so they figured they were safe.

Khalilzad lobbied Reagan not to sign, convincing him to let the civil war continue (his family were safely in Pakistan by then), and to keep the arms (including the deadly Stinger missiles) flowing to the mujahidin. It worked! The Russkies left anyway (hey, I thought commies were liars?). (Just imagine if Reagan had signed. The war over, a secular socialist regime in Afghanistan, millions of lives saved. No 9/11. No ISIS. “Raygun” remembered in history as a peacenik.)

Khalilzad’s jabs at Pakistan are sprinkled throughout the book. He smirks at Pakistanis who came to Kabul in the 1960s to enjoy its nightclubs and indulge in the guilty pleasure of Indian movies, banned in their own country. He writes that Pakistan’s wish to keep Afghanistan unstable is rooted in Islamabad’s (justified) fear that India would gain a dominant position in Kabul. Of course. India has always been at peace with Afghanistan, would be a good ally, and by sheer size would eclipse Pakistan when peace comes.

He was determined to make sure the extremists in the Afghan resistance, backed by Pakistan, would not become the dominant force. But he had to ensure the exact opposite by undermining the 1988 truce. This came back to haunt him when he became ambassador to Afghanistan in 2003.

Everyone knew that Pakistan was secretly aiding the Taliban. Lt. Gen. John Vines took over military headquarters in Kabul briefly, and recalled the enormous damage caused by sanctuaries in Cambodia and Laos during the Vietnam War. It was as if Pakistan had become the Cambodia and Laos to Afghanistan’s South Vietnam.

He whines about US mistakes (invading Iraq then bungling the occupation, the obsession with destroying Iran rather than negotiating, supporting the Pakistani dictator — sorry, he changed colours on that one). If only they’d listen to his recommendations (but they usually did!). Remember 1988, Zal? When you changed the course of history?

Despite the Iranians helping elect Reagan,3 the third-rate Hollywood actor was no Islamic Iranophile. As Afghanistan descended into chaos in 1980, those darned Iranians had had an Islamic revolution, and Reagan was “forced” to support the hated Saddam Husayn to defeat Iran’s Islamic revolutionaries, even as he was pumping arms and money into the hands of the Islamists in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and — until caught in flagrante — the Iranians themselves. Who needs Russiagate? The Iranians elected Reagan and he paid them off in arms. And he got away with it.

But Khalilzad doesn’t relish the deadly irony at work here. Indeed, it undermines whatever credibility the US has as world policeman. So he glosses right over it, failing to mention the October Surprise or secret US arms sales to Iran, even as the US was pressing countries around the world to cease arms sales to Iran.

His truth, his vision of America as the citadel of democracy, remains untarnished, “America was a miracle to me when I visited as a teenager, my outlook has not changed. A universal nation where people from everywhere can cooperate and work together under the rule of law.” Nothing can undermine his love of America, right or wrong (or insane).

So, it is encouraging when he argues that it is wrong to try to destroy Iran, relating instance after instance in Iraq and Afghanistan where Islamic Iran was measured in its resistance to the unceasing US aggression against it. Negotiating with Iran is productive, he told his bosses. Fighting it is just more foot-shooting.

But in a tribute to his MAD mentor Wohlstetter (and so there’s no hint that he’s soft on the Iranians), he orchestrated new UN sanctions against Iran in 2008, extending the asset freezes and called upon states to monitor the activities of Iranian banks, inspect Iranian ships and aircraft, and to monitor the movement of individuals involved with the program. His credo: (anti)diplomacy before invasion.

We know that plans to invade Iraq were underway as soon as George W. Bush hit the White House in 2001. But did you know that plans to invade Afghanistan were well underway by 1999, when Khalilzad was busy conning ex-king Zahir Shah to become the patragar to “mend Afghans’ broken dishes”?

Khalilzad tapped Afghan exiles (California solar engineer Ishaq Shahryar was fundraiser) and unveiled the face of the new Afghanistan in Rome in November 1999, where Zahir Shah blessed their (and the State Department’s) plan for a new Afghanistan. The delegates would spread out across the world to prepare public opinion for what was in the works (long before 9/11): the invasion of Afghanistan. As opposed to the Iraq invasion (read between the lines: he was against), that invasion Khalilzad heartily approved of.

The Afghan-born neocon insists that the US must maintain its overwhelming military position, and be prepared for more Middle East invasions, “in particular Saudi Arabia,” if the oil-rich Shi‘i eastern area erupts. He is still lost in his fantasy truth of the US “advancing liberal, democratic ideals.” In the meantime, he advises strengthening the military capabilities of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, and “push back against Iran’s gains in Yemen, Syria and Iraq.” Yes, negotiate; no, invade/roll back. When in doubt, throw some white phosphorus bombs into the mix.

His lack of anything insightful to say about these war zones is disappointing, but then he was out of the loop under the “commie” Obama. But he’s back in under Donald Trump. More America the beautiful, Russia etc. the bad. “Help Ukrainians bog down the Russians,” and “upgrade the Baltic states and Georgia’s defense capabilities.” But “cooperate with Russia on the space station and counterterrorism”?

And why didn’t Obama use the Libya tactic, a no-fly-zone to support the “moderate” Syrian opposition when the demonstrations against Bashar al-Asad were “largely peaceful”? Invasion lite? But, on the other hand, undertake direct military interventions with more caution.

His stint as ambassador in Iraq (2004–2007) was, according to him, a success. To his credit, he played an important role supporting the Sunni Awakening, bringing the Sunnis onside with the Shi‘i-dominated government of Nuri al-Maliki, who (Khalilzad claims) he convinced to work for a national unity government. He is right about Obama and US foreign policy in general. Too much turnover on vital issues that the incumbent knows nothing about. Obama’s imperialism lite (drones, more drones) just made matters worse in both the Afghan and Iraqi quagmires.

One does not come away with many truths or confessions from Khalilzad’s musings, but one gets a glimpse of the workings of Republican Oz.