Iqbal Siddiqui

Iqbal Siddiqui

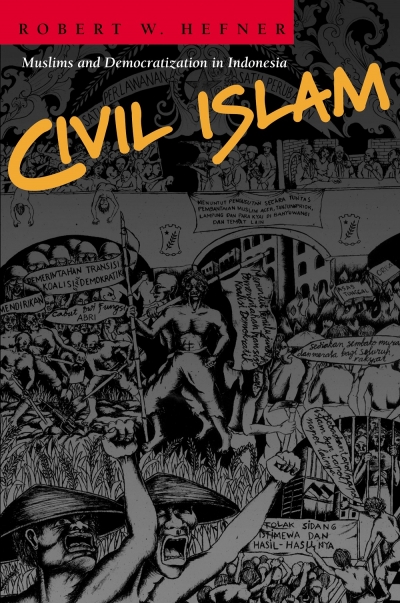

Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia by Robert W. Hefner. Pub: Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. Pp: 286. Pbk: $17.95 / £12.95.

This book is an example of the danger in taking western academic writings as sources for explanations of developments in Muslim countries and of Muslim history and society, and in regarding western academics working on such topics with anything other than caution, even suspicion. On the face of it, Robert Hefner’s book Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia comes across as sympathetic to Islam and Muslims. It certainly displays an immense knowledge and understanding of Indonesia in particular, and Muslim history more broadly. It is presented as a defence of Islam against non-Muslims who accept Samuel Huntington’s notorious "clash of civilizations" thesis, as well as against a militant minority of Muslims who — according to Hefner and others — are determined to prove Huntington right. When it comes down to it, however, Hefner, like Huntington, wants Muslims to accept their place in a West-dominated world; he just has a rather more sophisticated way of promoting that objective.

Hefner is professor of anthropology at Boston University. He started out working on identity, social memory and religious tradition among Muslims, Hindus and others in the Indonesian archipelago in the 1980s. From there, his interests moved to the political economy and politics of modern Indonesia, and then to Muslim political and intellectual elites, and Islam in modern south-east Asia. In 1998 he edited a book that has become a basic text on Islam and politics in the region, Islam in an Era of Nation-States: Politics and Religious Renewal in Muslim Southeast Asia.

The last two decades have also seen a massive surge in academic interest in the processes of democratization. From a universalist western liberal model that was believed to have triumphed with the collapse of the communist bloc, discourses on democratization have become increasingly relativist as the realization has dawned that the western model does not work on non-western societies. The result is that the study of democratization has moved increasingly into the area of political anthropology. Civil Islam can be seen as a result of the coming together of these two trends: Hefner’s gradual shift from the anthropological to the political, and the increasingly anthropological approach being taken in discussions of democratization.

Hefner himself opens the book with an explanation of his object in the context of reference to two other trends: "the diffusion of democratic ideas...around the world" and "the forceful reappearance of ethnic and religious issues in public affairs." In an opening chapter called ‘Democ-ratization’, he provides a summary of the direction of debates on the subject among social scientists in recent years, with a shift of focus from ideological first principles to actual processes of social and political change.

Like other social scientists, he highlights the widening of political space as a function of cultural, social and historical factors as well as technical and organizational modernity. He also points out that the processes by which democracy emerged in western countries were by no means uniform, and that it has taken different forms in different places as a result; and that it follows that in non-Western societies too, the processes and forms found are likely to be unique and contextually determined rather than following some ideal model derived from western liberal first principles.

So far, so good. But it is when Hefner starts talking about Islamic political thinking, and Muslim thought in Indonesia, that problems occur. Instead of being a detached discussion of different Muslim understandings of the subject of politics, relations of Islamic movements to non-Islamic systems, and so on, Hefner takes it upon himself to judge which idea is the most Islamically-legitimate trend of Muslim thought, and then produces a polemic panegyric in support of this trend and against all others, particularly those of ‘hardline’ political Islamic movements. The fact that this polemic is couched in the language of the academic social sciences, and supported by an impressive knowledge of Indo-nesian history, culture and society, only makes it all the more insidious.

The understanding of Islam that Hefner chooses to idolise is that of ‘liberal’ Muslim intellectuals such as Nurcholish Majid, Abdur-Rahman Wahid and Dawam Rahardjo, which he regards as tolerant, pluralistic, open-minded and socially progressive. A substantial part of the book consists of an extremely sympathetic account of their thinking, its philosophical and theological bases, and in particular their critiques of political Islam. He characterises their emergence in Indonesia as part of an "Islamic reformation in the late modern era" which is producing a "civil Islam which is not merely a facsimile of a Western original" (p. 12-13).

Against this paragon of a "democratic Islam", acceptable to the West because it is willing to operate within the bounds of a secular nation-state, he raises the spectre of an Islamic state that he misrepresents as a "fusion of state and society into an unchecked monolith", which some Muslims invoke simply in order to "justify harshly coercive policies" (p. 12). Lest there be any confusion, Hefner makes sure his readers can have no illusions: "the Islamic state," he tells us, "subordinates Muslim ideals to the dark intrigues of party bosses and religious thugs" (p. 20).

Where an academic’s role should be to clarify and inform his readers, Hefner’s object throughout is to condemn and libel Islamic intellectuals and thinkers whose ideas do not accord with his own opinion of what is Islamically legitimate. Such an attitude is presumptuous and unacceptable in a Muslim; coming from a non-Muslim, it is the height of arrogance.

This bias informs all of the book’s substantial discussions of Indonesian politics during the 1970s and 1980s, which he presents as a struggle between Sukarno and "conservative" Muslims supporting him, and liberal Muslims favouring a more democratic Indonesia. To uninformed readers, his ample use of primary sources and detailed knowledge of Indonesian politics might lend his analysis credibility, but the reality is that here too his analysis is appallingly skewed, with those he favours being given the benefit of every doubt, while the regime, its allies and other Muslim groups and leaders can do no right. In numerous cases, he appears to accept rumour, speculation and conspiracy theories uncritically for no other reason than they are conveniently condemnatory of forces that he wishes to discredit.

In his conclusion, Hefner makes his agenda perfectly clear. He sees Islamic thinkers as offering Muslims three possible responses to modernity. The first he characterises with an appalling caricature of the Islamic movement: "a repressively organic [response:] to strap on the body armor, ready one’s weapons and launch a holy war for society as a whole." The second he characterises as "separatist sectarianism." The third option is for a reformation that will create a "refigured religion, a civil one" which will create a kind of Muslim that can join him, "an American anthropologist who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s", as part of a global community of "believers in civility and democracy... the ideals for our age" — a global community, he all but adds, led by America as a champion of democracy and freedom in the world. (The impression created by the book is confirmed by a perusal of some of Hefner’s writings since September 11.)

This book shows precisely why Muslims must learn to be more cynical about western academia and academics. This is not a work of scholarship, but a work of political polemic. It is designed to advance a political agenda that promotes Muslims whom the West regards as easier to manipulate, and to lampoon Muslims who have different understandings. It is by no means alone in this among academic works on Islam, but it is particularly blatant. Huntington’s "clash of civilizations" thesis was a direct attack designed to put Muslims on the defensive. Hefner’s role, and that of others like him, is to play the nice guy to Huntington’s nasty guy.

"Come on," he seems to be telling us, "we aren’t all like Huntington. As long as you are sensible and do as we ask, we won’t let Huntington beat you up. So put away these silly ideas of independence, do as your good, sensible Muslim leaders say, instead of the awkward, antagonistic ones, and we can all get on just fine..."