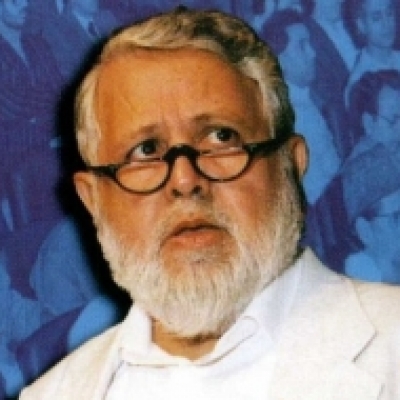

Kalim Siddiqui

Kalim SiddiquiThe Institute of Contemporary Islamic Thought (ICIT) this month issued a call for papers for another international conference on the Seerah. Here we reprint an abridged extract from DR KALIM SIDDIQUI’s last book, Stages of Islamic Revolution, in which he outlines his vision for the reinterpretation of the Seerah.

The history of Islam and Muslims has entered a new phase of rapid change. Muslims have realised that they are in a position to initiate, direct and control major change in their societies as well as to play a significant role in world politics. It is important that their drive for change in Muslim societies is directed by a profound understanding of the dynamics of change. The fact is that the states, organisations, cultures, movements, even civilisations that are most successful are those that can manage, direct, guide, influence, anticipate, manipulate and control the forces of change.

Islam is a permanent source of ever expanding knowledge in all fields. Islam has the capacity to develop, order and organise new information and knowledge. In other words, Islam orders and directs change, and internalises new knowledge born of new theories, experiments, experience, and evolving historical situations. This is why Islam insists that Muslims, all Muslims, living at any one time, must bring the prevailing historical situation under their control. Islam demands that the world’s physical resources are used to pursue the goals set by Islam for all mankind.

The Seerah (life) of the Prophet Muhammad, upon whom be peace, and his Sunnah (precept, example), are the basic models that exemplify Islam’s method of historical transformation. The Prophet began with a handful of individuals, organised them into small groups, then into larger goal-achieving systems, until the process led to the setting-up of the Islamic State. This clearly required the development of a versatile political process of incredible complexity and effectiveness. This process as a whole may be called the hikmah (wisdom), or method of the Prophet. The spiritual, intellectual and physical qualities inherent in the hikmah are an integral part of the Seerah and the Sunnah of the Prophet. So far scholars of the Seerah and the Sunnah have concentrated their attention almost exclusively on the meticulous research and recording of all that the Prophet did, said, ordered to be done and approved of; analytical and creative literature has been slow to emerge. The historical situation now facing Islam and Muslims demands that scholars turn their attention to the formulation of the underlying principles and structural forms of the Prophet’s hikmah. This area of the Seerah represents the unopened treasure-chest of Islam and its revealed paradigm.

The route to this treasure house of Islam lies through the development of a whole new range of literature based on the Seerah. There is no harm in the application of the speculative method to the largely descriptive literature on the Seerah that now exists. We must realise that Muhammad (pbuh), the last of all prophets, is a giant figure in world history. It is virtually impossible to distort his life and message, as the Orientalists have found to their cost. Besides, the Seerah is also protected by the Qur’an and the record of the systematic transformation of the historical situation that the Prophet brought about.

The vast intellectual energy that the Orientalist scholars in the west have spent in an organised attempt to damage the Prophet’s reputation has made no headway. In a very real sense the Prophet is defended by Allah subhanahu wa ta’ala Himself. The use of speculative methods of research by committed and muttaqi Muslim scholars, with ends and purposes clearly defined and known, may prove to be the key to unlocking the vast treasure-house that is the Seerah. For long periods of our history change of any kind was feared and discouraged by scholars and by ruling dynasties. This explains the almost total ban on ijtihad that is still found in the Sunni tradition. In the Shi’i tradition there was at first an equally rigid ban on ijtihad. Slowly, under pressure of conditions, fallacies and contradictions that could no longer be defended on theological grounds, the Shi’i doors were prised opened to allow some controlled ijtihad by a handful of mujtahids. This slow beginning under a new usuli school of ulama ultimately led to changes that made the Islamic Revolution in Iran possible.

For most of their history, Muslims accepted change so long as it was ad hoc and did not directly require change in theology. At no stage has change, its nature, direction and extent, been derived or devised from the Seerah and the Sunnah of the Prophet. Neither did the change ordered by rulers follow any criteria of good and bad, right and wrong, or desirable and undesirable. Change in Muslim societies, States and Empires has been the result of drift or the dynastic and political needs of rulers at any time. In short, change was not generated, controlled or directed by an intellectual movement that was also part of a political system of Islam, or at least part of an Islamic movement. This single factor alone, more than any other, eventually contributed to the collapse of dar al-Islam (House of Islam) and its colonisation by foreign powers.

The literature on the Seerah and the Sunnah offers an abundance of detail of situations, events, dates, places, names, ages, genealogy, battles, wars, campaigns, decision-making, sayings and so on. All this amounts to description of a very high order. But the straightforward description of facts on its own leads to limited understanding, especially if this understanding is essential as a guide to future action and policy. For example, it is known that the Prophet launched no fewer than 63 military campaigns from Madinah. Only a handful of these campaigns were purely defensive in nature, and the Prophet personally took part in fewer than half of them. These campaigns are a rich source of facts and other information about the situation in Madinah and its immediate environs. But little or no attempt has been made to draw a conceptual framework in which the military campaigns fit into a consistent whole in the Prophet’s method as a statesman, military leader and a da’i.

What is being suggested here is that abstraction and conceptualisation are essential processes that may now be applied to the vast literature of the Seerah and the Sunnah that now exists as a storehouse of meticulously researched data. It is concepts that help us to establish links between facts and events occurring at different times. Concepts also help us to derive lessons, information and new ideas from facts that may otherwise appear to be unrelated.

This requires a new type of scholarship that uses data from the Seerah and the Sunnah to generate theoretical formulations in areas of political, social and economic problems that Muslims, indeed all mankind, face now. We also need to generate new policy options, organisational structures and compatible behaviour patterns. The Seerah and the Sunnah must now be used to generate new disciplines of problem-solving knowledge in the short term. These can then be revised to keep pace with new and evolving historical situations. People living in distant parts of the world, and experiencing vastly different physical conditions and historical situations, would then be able to generate knowledge from the Seerah and the Sunnah relevant to their peculiar problems and situations.

Historians have only recently and reluctantly acknowledged that there would be no history without concepts, and that a value system is required to organise them into a meaningful narrative. The consistency of the literature on the Seerah and the Sunnah over hundreds of years is evidence of the firm grip Muslim historians have maintained over their use of concepts and the organising schema. Even the deviation of Muslim history from the path set for it by the Prophet, upon whom be peace, and the emergence of dynastic rule flying the flag of Islam, have failed to dent the veracity and credibility of the literature on the Seerah and the Sunnah.

It must also be noted that hundreds of years of hostile intellectual industry by Orientalist scholars, designed primarily to subvert the Seerah and the Sunnah of the Prophet, has made little headway. If it was possible to damage the reputation of the Prophet, or to distort his record, the Orientalists would have achieved it a long time ago. In fact, the only thing that has come close to damaging the Prophet and his Seerah and Sunnah is the Muslim failure on the stage of history.

If change is endemic in the human condition, as it clearly is, then the knowledge derived from the source of all knowledge must also expand in quality and quantity to cover all situations that human history encounters. For the Seerah and the Sunnah of the Prophet to become once again the engine of history, at least two things must happen: (a) an intellectual revolution within Islam which restores the Muslims’ behavioural proximity with the Prophet; and (b) the emergence of a transforming historical situation that owes its leadership, power, dynamism and success to its links with the Seerah and Sunnah of the Prophet, upon whom be peace.